3D math is all about measuring locations, distances, and angles precisely and mathematically in 3D space. The most frequently used framework to perform such calculations using a computer is called the Cartesian coordinate system. Cartesian mathematics was invented by (and is named after) a brilliant French philosopher, physicist, physiologist, and mathematician named René Descartes, who lived from 1596 to 1650. René Descartes is famous not just for inventing Cartesian mathematics, which at the time was a stunning unification of algebra and geometry. He is also well-known for making a pretty good stab of answering the question “How do I know something is true?”—a question that has kept generations of philosophers happily employed and does not necessarily involve dead sheep (which will perhaps disturbingly be a central feature of the next section), unless you really want it to. Descartes rejected the answers proposed by the Ancient Greeks, which are ethos (roughly, “because I told you so”), pathos (“because it would be nice”), and logos (“because it makes sense”), and set about figuring it out for himself with a pencil and paper.

This chapter is divided into four main sections.

- Section 1.1 reviews some basic principles of number systems and the first law of computer graphics.

- Section 1.2 introduces 2D Cartesian mathematics, the mathematics of flat surfaces. It shows how to describe a 2D cartesian coordinate space and how to locate points using that space.

- Section 1.3 extends these ideas into three dimensions. It explains left- and right-handed coordinate spaces and establishes some conventions used in this book.

- Section 1.4 concludes the chapter by quickly reviewing assorted prerequisites.

1.11D Mathematics

You're reading this book because you want to know about 3D mathematics, so you're probably wondering why we're bothering to talk about 1D math. Well, there are a couple of issues about number systems and counting that we would like to clear up before we get to 3D.

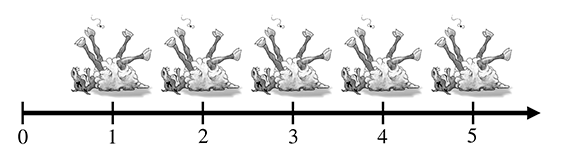

Figure 1.1One dead sheep

Figure 1.1One dead sheep

The natural numbers, often called the counting numbers, were invented millennia ago, probably to keep track of dead sheep. The concept of “one sheep” came easily (see Figure 1.1), then “two sheep,” “three sheep,” but people very quickly became convinced that this was too much work, and gave up counting at some point that they invariably called “many sheep.” Different cultures gave up at different points, depending on their threshold of boredom. Eventually, civilization expanded to the point where we could afford to have people sitting around thinking about numbers instead of doing more survival-oriented tasks such as killing sheep and eating them. These savvy thinkers immortalized the concept of zero (no sheep), and although they didn't get around to naming all of the natural numbers, they figured out various systems whereby they could name them if they really wanted to using digits such as 1, 2, etc. (or if you were Roman, M, X, I, etc.). Thus, mathematics was born.

The habit of lining sheep up in a row so that they can be easily counted leads to the concept of a number line, that is, a line with the numbers marked off at regular intervals, as in Figure 1.2. This line can in principle go on for as long as we wish, but to avoid boredom we have stopped at five sheep and used an arrowhead to let you know that the line can continue. Clearer thinkers can visualize it going off to infinity, but historical purveyors of dead sheep probably gave this concept little thought outside of their dreams and fevered imaginings.

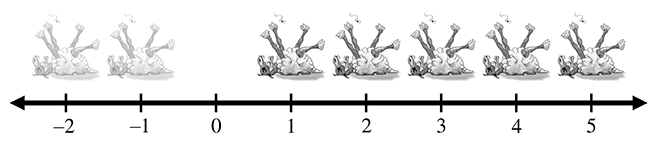

At some point in history, it was probably realized that sometimes, particularly fast talkers could sell sheep that they didn't actually own, thus simultaneously inventing the important concepts of debt and negative numbers. Having sold this putative sheep, the fast talker would in fact own “negative one” sheep, leading to the discovery of the integers, which consist of the natural numbers and their negative counterparts. The corresponding number line for integers is shown in Figure 1.3.

The concept of poverty probably predated that of debt, leading to a growing number of people who could afford to purchase only half a dead sheep, or perhaps only a quarter. This led to a burgeoning use of fractional numbers consisting of one integer divided by another, such as 2/3 or 111/27. Mathematicians called these rational numbers, and they fit in the number line in the obvious places between the integers. At some point, people became lazy and invented decimal notation, writing “3.1415” instead of the longer and more tedious 31415/10000, for example.

After a while it was noticed that some numbers that appear to turn up in everyday life were not

expressible as rational numbers. The classic example is the ratio of the circumference of a circle

to its diameter, usually denoted

The truth is, however, that real numbers are nothing more than a polite fiction. They are a

relatively harmless delusion, as any reputable physicist will tell you. The universe seems to be

not only discrete, but also finite. If there are a finite amount of discrete things in the

universe, as currently appears to be the case, then it follows that we can only count to a certain

fixed number, and thereafter we run out of things to count on—not only do we run out of dead

sheep, but toasters, mechanics, and telephone sanitizers, too. It follows that we can describe the

universe using only discrete mathematics, and only requiring the use of a finite subset of the

natural numbers at that (large, yes, but finite). Somewhere, someplace there may be an alien

civilization with a level of technology exceeding ours who have never heard of continuous

mathematics, the fundamental theorem of calculus, or even the concept of infinity; even if we

persist, they will firmly but politely insist on having no truck with

So why do we use continuous mathematics? Because it is a useful tool that lets us do engineering. But the real world is, despite the cognitive dissonance involved in using the term “real,” discrete. How does that affect you, the designer of a 3D computer-generated virtual reality? The computer is, by its very nature, discrete and finite, and you are more likely to run into the consequences of the discreteness and finiteness during its creation than you are likely to in the real world. C++ gives you a variety of different forms of number that you can use for counting or measuring in your virtual world. These are the short, the int, the float and the double, which can be described as follows (assuming current PC technology). The short is a 16-bit integer that can store 65,536 different values, which means that “many sheep” for a 16-bit computer is 65,537. This sounds like a lot of sheep, but it isn't adequate for measuring distances inside any reasonable kind of virtual reality that take people more than a few minutes to explore. The int is a 32-bit integer that can store up to 4,294,967,296 different values, which is probably enough for your purposes. The float is a 32-bit value that can store a subset of the rationals (slightly fewer than 4,294,967,296 of them, the details not being important here). The double is similar, using 64 bits instead of 32.

The bottom line in choosing to count and measure in your virtual world using ints, floats, or doubles is not, as some misguided people would have it, a matter of choosing between discrete shorts and ints versus continuous floats and doubles; it is more a matter of precision. They are all discrete in the end. Older books on computer graphics will advise you to use integers because floating-point hardware is slower than integer hardware, but this is no longer the case. In fact, the introduction of dedicated floating point vector processors has made floating-point arithmetic faster than integer in many common cases. So which should you choose? At this point, it is probably best to introduce you to the first law of computer graphics and leave you to think about it.

We will be doing a lot of trigonometry in this book. Trigonometry

involves real numbers such as

1.22D Cartesian Space

You probably have used 2D Cartesian coordinate systems even if you have never heard the term “Cartesian” before. “Cartesian” is mostly just a fancy word for “rectangular.” If you have ever looked at the floor plans of a house, used a street map, seen a football1 game, or played chess, you have some exposure to 2D Cartesian coordinate spaces.

This section introduces 2D Cartesian mathematics, the mathematics of flat surfaces. It is divided into three main subsections.

- Section 1.2.1 provides a gentle introduction to the concept of 2D Cartesian space by imagining a fictional city called Cartesia.

-

Section 1.2.2 generalizes this concept to arbitrary or abstract 2D

Cartesian spaces. The main concepts introduced are

- the origin

-

the

- orienting the axes in 2D

-

Section 1.2.3 describes how to

specify the location of a point in the 2D plane using Cartesian

1.2.1An Example: The Hypothetical City of Cartesia

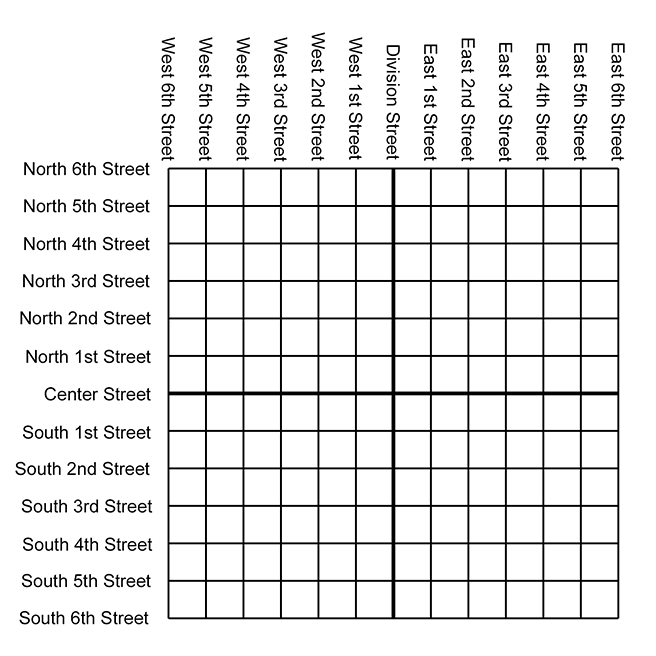

Let's imagine a fictional city named Cartesia. When the Cartesia city planners were laying out the streets, they were very particular, as illustrated in the map of Cartesia in Figure 1.4.

As you can see from the map, Center Street runs east-west through the middle of town. All other east-west streets (parallel to Center Street) are named based on whether they are north or south of Center Street, and how far they are from Center Street. Examples of streets that run east-west are North 3rd Street and South 15th Street.

The other streets in Cartesia run north-south. Division Street runs north-south through the middle of town. All other north-south streets (parallel to Division Street) are named based on whether they are east or west of Division Street, and how far they are from Division Street. So we have streets such as East 5th Street and West 22nd Street.

The naming convention used by the city planners of Cartesia may not be creative, but it certainly is practical. Even without looking at the map, it is easy to find the donut shop at North 4th and West 2nd. It's also easy to determine how far you will have to drive when traveling from one place to another. For example, to go from that donut shop at North 4th and West 2nd, to the police station at South 3rd and Division, you would travel seven blocks south and two blocks east.

1.2.2Arbitrary 2D Coordinate Spaces

Before Cartesia was built, there was nothing but a large flat area of land. The city planners arbitrarily decided where the center of town would be, which direction to make the roads run, how far apart to space the roads, and so forth. Much like the Cartesia city planners laid down the city streets, we can establish a 2D Cartesian coordinate system anywhere we want—on a piece of paper, a chessboard, a chalkboard, a slab of concrete, or a football field.

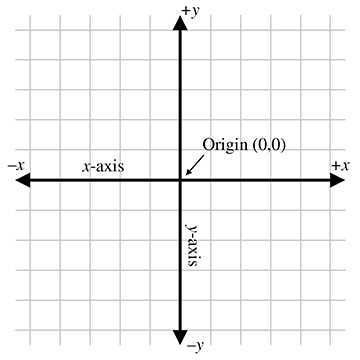

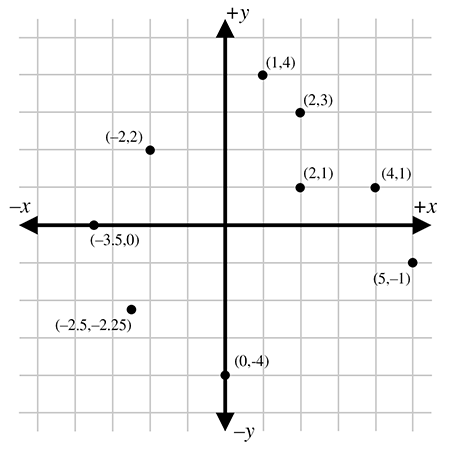

Figure 1.5 shows a diagram of a 2D Cartesian coordinate system.

As illustrated in Figure 1.5, a 2D Cartesian coordinate space is defined by two pieces of information:

- Every 2D Cartesian coordinate space has a special location, called the origin, which is the “center” of the coordinate system. The origin is analogous to the center of the city in Cartesia.

- Every 2D Cartesian coordinate space has two straight lines that pass through the origin. Each line is known as an axis and extends infinitely in two opposite directions. The two axes are perpendicular to each other. (Actually, they don't have to be, but most of the coordinate systems we will look at will have perpendicular axes.) The two axes are analogous to Center and Division streets in Cartesia. The grid lines in the diagram are analogous to the other streets in Cartesia.

At this point it is important to highlight a few significant differences between Cartesia and an abstract mathematical 2D space:

- The city of Cartesia has official city limits. Land outside of the city limits is not considered part of Cartesia. A 2D coordinate space, however, extends infinitely. Even though we usually concern ourselves with only a small area within the plane defined by the coordinate space, in theory this plane is boundless. Also, the roads in Cartesia go only a certain distance (perhaps to the city limits) and then they stop. In contrast, our axes and grid lines extend potentially infinitely in two directions.

- In Cartesia, the roads have thickness. In contrast, lines in an abstract coordinate space have location and (possibly infinite) length, but no real thickness.

- In Cartesia, you can drive only on the roads. In an abstract coordinate space, every point in the plane of the coordinate space is part of the coordinate space, not just the “roads.” The grid lines are drawn only for reference.

In Figure 1.5, the horizontal axis is called the

The city planners of Cartesia could have made Center Street run north-south instead of east-west.

Or they could have oriented it at a completely arbitrary angle. For example, Long Island, New York,

is reminiscent of Cartesia, where for convenience the “streets” (1st Street, 2nd Street etc.) run

across the island, and the “avenues” (1st Avenue, 2nd Avenue, etc.) run along its long axis. The

geographic orientation of the long axis of the island is an arbitrary result of nature. In the

same way, we are free to orient our axes in any way that is convenient to us. We must also decide

for each axis which direction we consider to be positive.

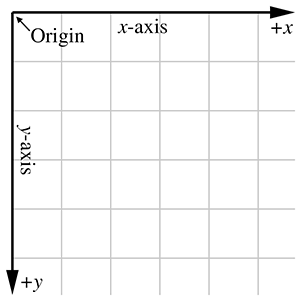

For example, when working with images on a computer screen, it is customary to use the coordinate

system shown in Figure 1.6. Notice that the origin is in the upper left-hand

corner,

Unfortunately, when Cartesia was being laid out, the only mapmakers were in the neighboring town of Dyslexia. The minor-level functionary who sent the contract out to bid neglected take into account that the dyslectic mapmaker was equally likely to draw his maps with north pointing up, down, left, or right. Although he always drew the east-west line at right angles to the north-south line, he often got east and west backwards. When his boss realized that the job had gone to the lowest bidder, who happened to live in Dyslexia, many hours were spent in committee meetings trying to figure out what to do. The paperwork had been done, the purchase order had been issued, and bureaucracies being what they are, it would be too expensive and time-consuming to cancel the order. Still, nobody had any idea what the mapmaker would deliver. A committee was hastily formed.

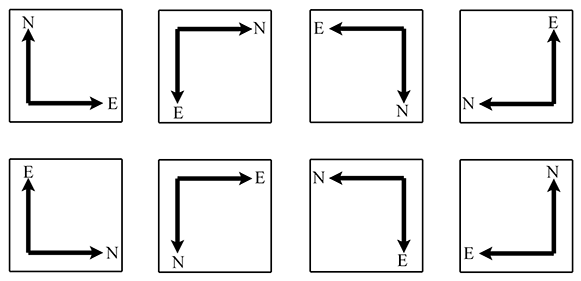

The committee fairly quickly decided that there were only eight possible orientations that the mapmaker could deliver, shown in Figure 1.7. In the best of all possible worlds, he would deliver a map oriented as shownin the top-left rectangle, with north pointing to the top of thepage and east to the right, which is what people usually expect. A subcommittee formed for the task decided to name this the normalorientation.

After the meeting had lasted a few hours and tempers were beginning to fray, it was decided that the other three variants shown in the top row of Figure 1.7 were probably acceptable too, because they could be transformed to the normal orientation by placing a pin in the center of the page and rotating the map around the pin. (You can do this, too, by placing this book flat on a table and turning it.) Many hours were wasted by tired functionaries putting pins into various places in the maps shown in the second row of Figure 1.7, but no matter how fast they twirled them, they couldn't seem to transform them to the normal orientation. It wasn't until everybody important had given up and gone home that a tired intern, assigned to clean up the used coffee cups, noticed that the maps in the second row can be transformed into the normal orientation by holding them up against a light and viewing them from the back. (You can do this, too, by holding Figure 1.7 up to the light and viewing it from the back—you'll have to turn it, too, of course.) The writing was backwards too, but it was decided that if Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) could handle backwards writing in 15th century, then the citizens of Cartesia, though by no means his intellectual equivalent (probably due to daytime TV), could probably handle it in the 21st century.

In summary, no matter what orientation we choose for the

1.2.3Specifying Locations in 2D Using Cartesian Coordinates

A coordinate space is a framework for specifying location precisely. A gentleman of Cartesia could,

if he wished to tell his lady love where to meet him for dinner, for example, consult the map in

Figure 1.4 and say, “Meet you at the corner of East 2nd Street and North 4th

Street.” Notice that he specifies two coordinates, one in the horizontal dimension (East 2nd

Street, listed along the top of the map in Figure 1.4) and one in the vertical

dimension (North 4th Street, listed along the left of the map). If he wished to be concise he could

abbreviate the “East 2nd Street” to “2” and the “North 4th Street” to “4” and say to his

lady love, somewhat cryptically, “Meet you at (

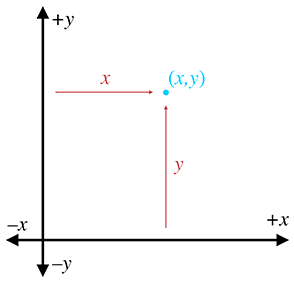

The ordered pair (

Analogous to the street names in Cartesia, each of the two coordinates specifies which side of the

origin the point is on and how far away the point is from the origin in that direction. More

precisely, each coordinate is the

signed distance (that is, positive in one direction and negative in the other) to one of the

axes, measured along a line parallel to the other axis. Essentially, we use positive coordinates

for east and north streets and negative coordinates for south and west streets. As shown in

Figure 1.8, the

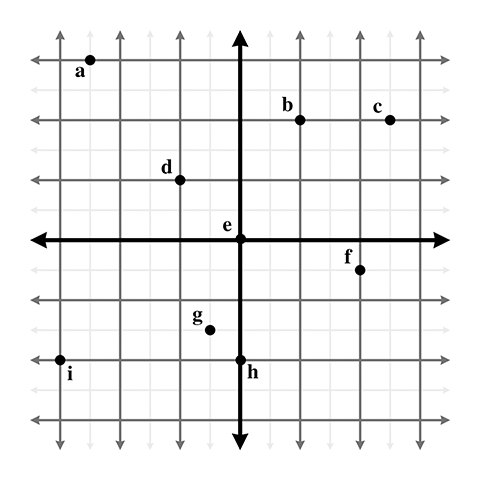

Figure 1.9 shows several points and their Cartesian coordinates. Notice that the

points to the left of the

Let's take a closer look at the grid lines usually shown in a

diagram. Notice that a vertical grid line is composed of points that

all have the same

1.33D Cartesian Space

The previous sections have explained how the Cartesian coordinate system works in 2D. Now it's time to leave the flat 2D world and think about 3D space.

It might seem at first that 3D space is only “50%more complicated” than 2D. After all, it's just one more dimension, and we already had two. Unfortunately, this is not the case. For a variety of reasons, 3D space is more than incrementally more difficult than 2D space for humans to visualize and describe. (One possible reason for this difficulty could be that our physical world is 3D, whereas illustrations in books and on computer screens are 2D.) It is frequently the case that a problem that is “easy” to solve in 2D is much more difficult or even undefined in 3D. Still, many concepts in 2D do extend directly into 3D, and we frequently use 2D to establish an understanding of a problem and develop a solution, and then extend that solution into 3D.

This section extends 2D Cartesian math into 3D. It is divided into four major subsections.

-

Section 1.3.1 begins the extension of 2D into 3D by adding a third axis. The

main concepts introduced are

-

the

-

the

-

the

-

Section 1.3.2 describes how to specify the

location of a point in the 3D plane using Cartesian

-

Section 1.3.3 introduces the concepts of left-handed and right-handed 3D

coordinate spaces. The main concepts introduced are

- the hand rule, an informal definition for left-handed and right-handed coordinate spaces

- differences in rotation in left-handed and right-handed coordinate spaces

- how to convert between the two

- neither is better than the other, only different

- Section 1.3.4 describes some conventions used in this book.

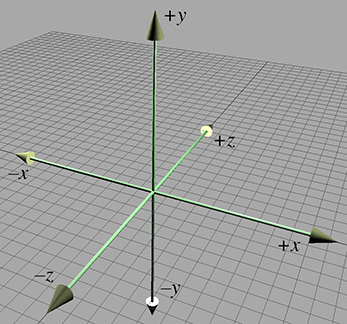

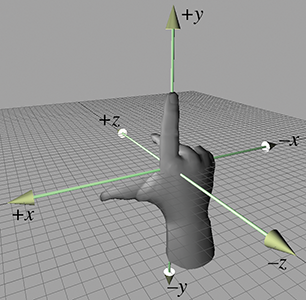

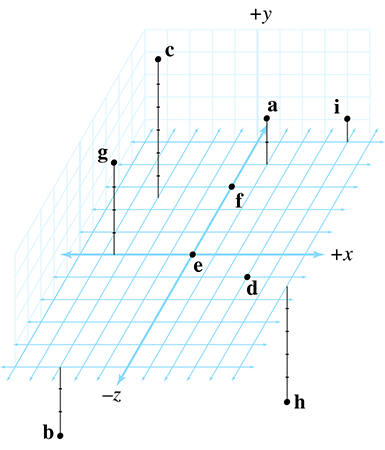

1.3.1Extra Dimension, Extra Axis

In 3D, we require three axes to establish a coordinate system. The first two axes are called the

As discussed in Section 1.2.2, it is customary in 2D for

As mentioned earlier, it is not entirely appropriate to say that the

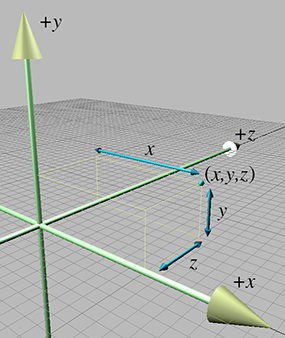

1.3.2Specifying Locations in 3D

In 3D, points are specified using three numbers,

1.3.3Left-handed versus Right-handed Coordinate Spaces

As we discussed in Section 1.2.2, all 2D coordinate systems are “equal” in the sense

that for any two 2D coordinate spaces

Figure 1.5 shows the “standard” 2D

coordinate space. Notice that the difference between this

coordinate space and “screen” coordinate space shown

Figure 1.6 is that the

Let's see how this idea extends into 3D. Examine

Figure 1.10 once more. We stated earlier that

Now, can we rotate the coordinate system around such that things line up with the original coordinate system? As it turns out, we cannot. We can rotate things to line up two axes at a time, but the third axes always points in the wrong direction! (If you have trouble visualizing this, don't worry. In just a moment we will illustrate this principle in more concrete terms.)

All 3D coordinate spaces are not equal, in the sense that some pairs of coordinate systems cannot be rotated to line up with each other. There are exactly two distinct types of 3D coordinate spaces: left-handed coordinate spaces and right-handed coordinate spaces. If two coordinate spaces have the same handedness, then they can be rotated such that the axes are aligned. If they are of opposite handedness, then this is not possible.

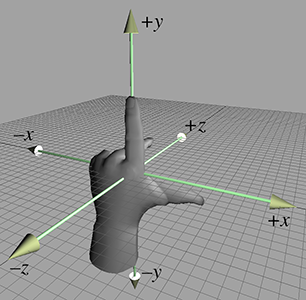

What exactly do “left-handed” and “right-handed” mean? The most intuitive way to identify the

handedness of a particular coordinate system is to use, well, your hands!

With your left hand, make an `L' with your thumb and index finger.2 Your thumb should be pointing to your right, and your index finger should be pointing

up. Now extend your third finger3 so it points directly forward. You have just formed a left-handed coordinate

system. Your thumb, index finger, and third finger point in the

Now perform the same experiment with your right hand. Notice that your index finger still points

up, and your third finger points forward. However, with your right hand, your thumb will point to

the left. This is a right-handed coordinate system. Again, your thumb, index finger, and third

finger point in the

Try as you might, you cannot rotate your hands into a position such that all three fingers simultaneously point the same direction on both hands. (Bending your fingers is not allowed.)

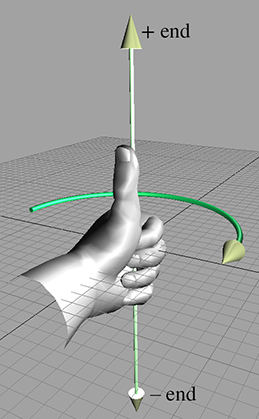

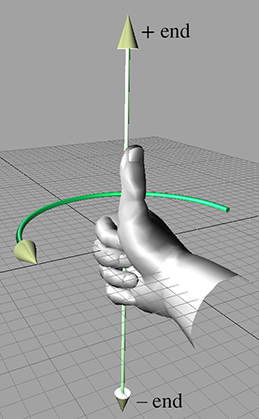

Left-handed and right-handed coordinate systems also differ in the definition of “positive

rotation.” Let's say we a have line in space and we need to rotate about this line by a

specified angle. We call this line an axis of rotation, but don't think that the word

axis implies that we're talking only about one of the cardinal axes (the

|

|

| Left-hand rule | Right-hand rule |

As you can see, in a left-handed coordinate system, positive rotation rotates clockwise when viewed from the positive end of the axis, and in a right-handed coordinate system, positive rotation is counterclockwise. Table 1.1 shows what happens when we apply this general rule to the specific case of the cardinal axes.

| When looking towards the origin from… |

Positive rotation | Negative rotation |

| Left-handed: Clockwise | Left-handed: Counterclockwise | |

| Right-handed: Counterclockwise | Right-handed: Clockwise | |

Any left-handed coordinate system can be transformed into a right-handed coordinate system, or vice

versa. The simplest way to do this is by swapping the positive and negative ends of one axis.

Notice that if we flip two axes, it is the same as rotating the coordinate space

Both left-handed and right-handed coordinate systems are perfectly valid, and despite what you

might read in other books, neither is “better” than the other. People in various fields of study

certainly have preferences for one or the other, depending on their backgrounds. For example, some

newer computer graphics literature uses left-handed coordinate systems, whereas traditional

graphics texts and more math-oriented linear algebra people tend to prefer right-handed coordinate

systems. Of course, these are gross generalizations, so always check to see what coordinate system

is being used. The bottom line, however, is that in many cases it's just a matter of a negative

sign in the

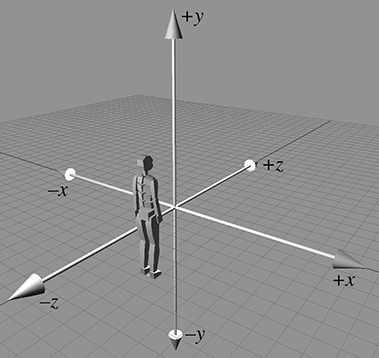

1.3.4Some Important Conventions Used in This Book

When designing a 3D virtual world, several design decisions have to be made beforehand, such as

left-handed or right-handed coordinate system, which direction is

Different situations can call for different conventions, in the sense that certain tasks can be easier if you adopt the right conventions. Usually, however, it is not a major deal as long as you establish the conventions early in your design process and stick to them. (In fact, the choice is most likely thrust upon you by the engine or framework you are using, because very few people start from scratch these days.) All of the basic principles discussed in this book are applicable regardless of the conventions used. For the most part, all of the equations and techniques given are applicable regardless of convention, as well.4 However, in some cases there are some slight, but critical, differences in application dealing with left-handed versus right-handed coordinate spaces. When those differences arise, we will point them out.

We use a left-handed coordinate system in this book. The

1.4Odds and Ends

In this book, we spend a lot of time focusing on some crucial material that is often relegated to a terse presentation tucked away in an appendix in the books that consider this material a prerequisite. We, too, must assume a nonzero level of mathematical knowledge from the reader, or else every book would get no further than a review of first principles, and so we also have our terse presentation of some prerequisites. In this section we present a few bits of mathematical knowledge with which most readers are probably familiar, but might need a quick refresher.

1.4.1Summation and Product Notation

Summation notation is a shorthand way to write the sum of a list of things. It's sort of like a mathematical for loop. Let's look at an example:

Summation notation

The variable

Summation notation is also known as sigma notation because that cool-looking symbol that looks like an E is the capital version of the Greek letter sigma.

A similar notation is used when we are taking the product of a series of values, only we use the

symbol

1.4.2Interval Notation

Several times in this book, we refer to a subset of the real number line using interval

notation. The notation

Occasionally, we encounter half-open intervals, which include one endpoint but exclude the

other. These are denoted with a lopsided5 notation such as

Notice that the notation

1.4.3Angles, Degrees, and Radians

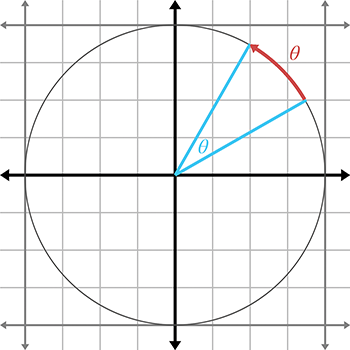

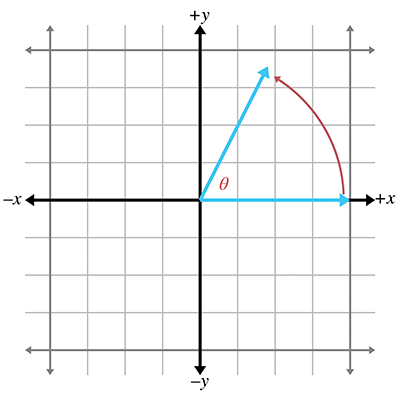

An angle measures an amount of rotation in the plane. Variables representing angles are often

assigned the Greek letter

Humans usually measure angles using degrees. One degree measures 1/360th of a revolution,

so

The circumference of a unit circle is

Since

In the next section, Table 1.2 will list several angles in both degree and radian format.

1.4.4Trig Functions

There are many ways to define the elementary trig functions. In this section, we define them using

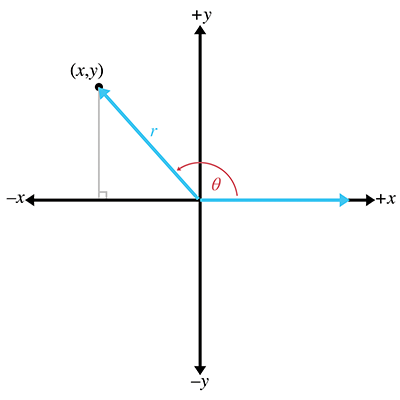

the unit circle. In two dimensions, if we begin

with a unit ray pointing towards

The

You can easily remember which is which because they are in alphabetical order:

The secant, cosecant, tangent, and cotangent are also useful trig functions. They can be defined in terms of the the sine and cosine:

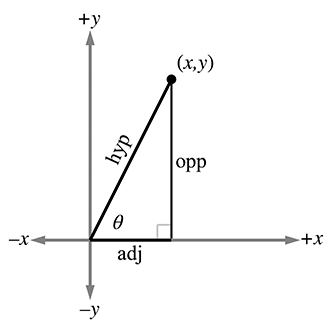

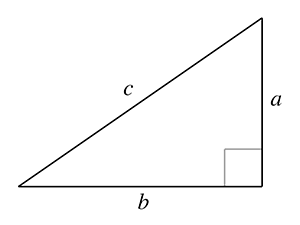

If we form a right triangle using the rotated ray as the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right

angle), we see that

The primary trig functions are defined by the following ratios:

Because of the properties of similar triangles, the above equations apply even when the hypotenuse

is not of unit length. However, they do not apply when

Table 1.2 shows several different angles, expressed in degrees and radians, and the values of their principal trig functions.

1.4.5Trig Identities

In this section we present a number of basic relationships between the trig functions. Because we assume in this book that the reader has some prior exposure to trigonometry, we do not develop or prove these theorems. The proofs can be found online or in any trigonometry textbook.

A number of identities can be derived based on the symmetry of the unit circle:

Basic identities related to symmetryPerhaps the most famous and basic identity concerning the right triangle, one that most readers learned in their primary education, is the Pythagorean theorem. It says that the sum of the squares of the two legs of a right triangle is equal to the square of the hypotenuse. Or, more famously, as shown in Figure 1.20,

Pythagorean theorem

By applying the Pythagorean theorem to the unit circle, one can deduce the identities

Pythagorean identitiesThe following identities involve taking a trig function on the sum or difference of two angles:

Sum and difference identities

If we apply the sum identities to the special case where

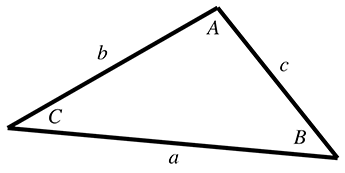

We often need to solve for an unknown side length or angle in a triangle, in terms of the known side lengths or angles. For these types of problems the law of sines and law of cosines are helpful. The formula to use will depend on which values are known and which value is unknown. Figure 1.21 illustrates the notation and shows that these identities hold for any triangle, not just right triangles:

Exercises

-

Give the coordinates of the following points. Assume the standard 2D conventions. The

darker grid lines represent one unit.

-

Give the coordinates of the following points:

- List the 48 different possible ways that the 3D axes may be assigned to the directions “north,” “east,” and “up.” Identify which of these combinations are left-handed, and which are right-handed.

-

In the popular modeling program

3DS Max, the default

orientation of the axes is for

- (a)Is this a left- or right-handed coordinate space?

- (b)How would we convert 3D coordinates from the coordinate system used by 3DS Max into points we could use with our coordinate conventions discussed in Section 1.3.4?

- (c)What about converting from our conventions to the 3DS Max conventions?

-

A common convention in aerospace is that

- (a)Is this a left- or right-handed coordinate space?

- (b)How would we convert 3D coordinates from these aerospace conventions into our conventions?

- (c)What about converting from our conventions to the aerospace conventions?

-

In a left-handed coordinate system:

- (a)when looking from the positive end of an axis of rotation, is positive rotation clockwise (CW) or counterclockwise (CCW)?

- (b)when looking from the negative end of an axis of rotation, is positive rotation CW or CCW?

- (c)when looking from the positive end of an axis of rotation, is positive rotation CW or CCW?

- (d)when looking from the negative end of an axis of rotation, is positive rotation CW or CCW?

-

Compute the following:

(a)

-

Convert from degrees to radians:

(a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) (g) (h) (i) (j) -

Convert from radians to degrees:

(a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) (g) (h) (i) (j) -

In The Wizard of Oz, the scarecrow receives his degree

from the wizard and blurts out this mangled version of the Pythagorean theorem:

The sum of the square roots of any two sides of an isosceles triangle is equal to the square root of the remaining side.Apparently the scarecrow's degree wasn't worth very much, since this “proof that he had a brain” is actually wrong in at least two ways.9 What should the scarecrow have said?

-

Confirm the following:

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (a)

weekend radio show Whaddya know?

- This sentence works no matter which sport you think we are referring to with the word “football.” Well, OK, it works a little better with American football because of the clearly marked yard lines.

- You may have to put the book down.

- This may require some dexterity. The authors advise that you not do this in public without first practicing privately, to avoid offending innocent bystanders.

- This is due to a fascinating and surprising symmetry in nature. You might say that nature doesn't know if we are using left- or right-handed coordinates. There's a really interesting discussion in The Feynman Lectures on Physics about how it is impossible without very advanced physics to describe the concepts of “left” or “right” to someone without referencing some object you both have seen.

- And confusing to the delimiter matching feature of your text editor.

-

One prerequisite that we do not assume in

this book is familiarity with the Greek alphabet. The symbol

- The number 360 is a relatively arbitrary choice, which may have had its origin in primitive calendars, such as the Persian calendar, which divided the year into 360 days. This error was never corrected to 365 because the number 360 is so darn convenient. The number 360 has a whopping 22 divisors (not counting itself and 1): 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 18, 20, 24, 30, 36, 40, 45, 60, 72, 90, 120, and 180. This means 360 can be divided evenly in a large number of cases without needing fractions, which was apparently a good thing to early civilizations. As early as 1750 BCE the Babylonians had devised a sexagesimal (base 60) number system. The number 360 is also large enough so that precision to the nearest whole degree is sufficient in many circumstances.

- There is a well-known story about the mathematician Karl Friedrich Gauss solving this problem in only a few seconds while a student in primary school. As the story goes, his teacher wanted to occupy the students by having them add the numbers 1 to 100 and turn in their answers at the end of class. However, mere seconds after being given this assignment, Gauss handed the correct answer to his teacher as the teacher and the rest of the class gazed in astonishment at the young Gauss.

- Homer Simpson repeated the same jibberish after putting on a pair of glasses found in a toilet. A man in a nearby stall corrected him on one of his errors. So if you saw that episode of The Simpsons, then you have a headstart on this question, but not the whole answer.