10 to 12 days before exposure to the vector.

Vectors are the formal mathematical entities we use to do 2D and 3D math. The word vector has two distinct but related meanings. Mathematics books, especially those on linear algebra, tend to focus on a rather abstract definition, caring about the numbers in a vector but not necessarily about the context or actual meaning of those numbers. Physics books, on the other hand, tend towards an interpretation that treats a vector as a geometric entity to the extent that they avoid any mention of the coordinates used to measure the vector, when possible. It's no wonder that you can sometimes find people from these two disciplines correcting one another on the finer points of “how vectors really work.” Of course the reality is that they are both right,1 and to be proficient with 3D math, we need to understand both interpretations of vectors and how the two interpretations are related.

This chapter introduces the concept of vectors. It is divided into the following sections.

- Section 2.1 covers some of the basic mathematical properties of vectors.

- Section 2.2 gives a high-level introduction to the geometric properties of vectors.

- Section 2.3 connects the mathematical definition with the geometric one and discusses how vectors work within the framework of Cartesian coordinates.

- Section 2.4 discusses the often confusing relationship between points and vectors and considers the rather philosophical question of why it is so difficult to make absolute measurements.

- Sections 2.5–2.12 discuss the fundamental calculations we can perform with vectors, considering both the algebra and geometric interpretations of each operation.

- Section 2.13 presents a list of helpful vector algebra laws.

2.1Mathematical Definition of Vector,

and Other Boring Stuff

To mathematicians, a vector is a list of numbers. Programmers will recognize the synonymous term array. Notice that the STL template array class in C++ is named vector, and the basic Java array container class is java.util.Vector. So mathematically, a vector is nothing more than an array of numbers.

Yawn… If this abstract definition of a vector doesn't inspire you, don't worry. Like many mathematical subjects, we must first introduce some terminology and notation before we can get to the “fun stuff.”

Mathematicians distinguish between vector and scalar (pronounced “SKAY-lur”) quantities. You're already an expert on scalars—scalar is the technical term for an ordinary number. We use this term specifically when we wish to emphasize that a particular quantity is not a vector quantity. For example, as we will discuss shortly, “velocity” and “displacement” are vector quantities, whereas “speed” and “distance” are scalar quantities.

The dimension of a vector tells how many numbers the vector contains. Vectors may be of any positive dimension, including one. In fact, a scalar can be considered a 1D vector. In this book, we primarily are interested in 2D, 3D, and (later) 4D vectors.

When writing a vector, mathematicians list the numbers surrounded by square brackets, for

example,

A vector written vertically is known as a column vector. This book uses both notations. For now, the distinction between row and column vectors won't matter. However, in Section 4.1.7 we discuss why in certain circumstances the distinction is critical.

When we wish to refer to the individual components in a vector, we use subscript notation. In

math literature, integer indices are used to access the elements. For example

Notice that the components of a 4D vector are not in alphabetical

order. The fourth value is

Now let's talk about some important typeface conventions that are used in this book. As you know, variables are placeholder symbols used to stand for unknown quantities. In 3D math, we work with scalar, vector, and (later) matrix quantities. In the same way that it's important in a C++ or Java program to specify what type of data is stored by a variable, it is important when working with vectors to be clear what type of data is represented by a particular variable. In this book, we use different fonts for variables of different types:

-

Scalar variables are represented by lowercase Roman or Greek

letters in italics:

-

Vector variables of any dimension are represented

by lowercase letters in boldface:

-

Matrix variables are represented using uppercase

letters in boldface:

Before we go any further, a bit of context is in order concerning the perspective that we are

adopting about vectors. The branch of mathematics that deals primarily with vectors and matrices

is called linear algebra, a subject that assumes the abstract definition given previously:

a vector is an array of numbers. This highly generalized approach allows for the exploration of a

large set of mathematical problems. In linear algebra, vectors and matrices of dimension

Our focus is geometric, so we omit many details and concepts of linear algebra that do not

further our understanding of 2D or 3D geometry. Even though we occasionally discuss properties

or operations for vectors of an arbitrary dimension

2.2Geometric Definition of Vector

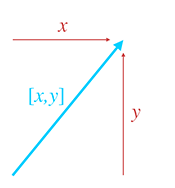

Now that we have discussed what a vector is mathematically, let's look at a more geometric interpretation of vectors. Geometrically speaking, a vector is a directed line segment that has magnitude and direction.

- The magnitude of a vector is the length of the vector. A vector may have any nonnegative length.

- The direction of a vector describes which way the vector is pointing in space. Note that “direction” is not exactly the same as “orientation,” a distinction we will reexamine in Section 8.1.

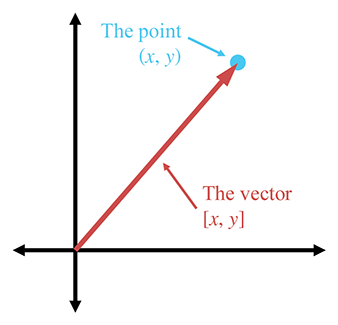

Figure 2.1A 2D vector

Figure 2.1A 2D vector

Let's look at a vector. Figure 2.1 shows an illustration of a vector in 2D.

It looks like an arrow, right? This is the standard way to represent a vector graphically, since the two defining characteristics of a vector are captured: its magnitude and direction.

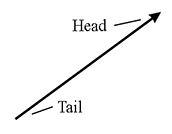

We sometimes refer to the head and tail of a vector. As shown in Figure 2.2, the head is the end of the vector with the arrowhead on it (where the vector “ends”), and the tail is the other end (where the vector “starts”).

Where is this vector? Actually, that is not an appropriate question. Vectors do not have position, only magnitude and direction. This may sound impossible, but many quantities we deal with on a daily basis have magnitude and direction, but no position. Consider how the two statements below could make sense, regardless of the location where they are applied.

- Displacement. “Take three steps forward.” This sentence seems to be all about positions, but the actual quantity used in the sentence is a relative displacement and does not have an absolute position. This relative displacement consists of a magnitude (3 steps) and a direction (forward), so it could be represented by a vector.

- Velocity. “I am traveling northeast at 50 mph.” This sentence describes a quantity that has magnitude (50 mph) and direction (northeast), but no position. The concept of “northeast at 50 mph” can be represented by a vector.

Notice that displacement and velocity are technically different from the terms distance and speed. Displacement and velocity are vector quantities and therefore entail a direction, whereas distance and speed are scalar quantities that do not specify a direction. More specifically, the scalar quantity distance is the magnitude of the vector quantity displacement, and the scalar quantity speed is the magnitude of the vector quantity velocity.

Because vectors are used to express displacements and relative differences between things, they can describe relative positions. (“My house is 3 blocks east of here.”) However, you should not think of a vector as having an absolute position itself, instead, remember that it is describing the displacement from one position to another, in this case from “here” to “my house.” (More on relative versus absolute position in Section 2.4.1.) To help enforce this, when you imagine a vector, picture an arrow. Remember that the length and direction of this arrow are significant, but not the position.

Since vectors do not have a position, we can represent them on a diagram anywhere we choose, provided that the length and direction of the vector are represented correctly. We often use this fact to our advantage by sliding the vector around into a meaningful location on a diagram.

Now that we have the big picture about vectors from a mathematical and geometric perspective, let's learn how to work with vectors in the Cartesian coordinate system.

2.3Specifying Vectors with Cartesian Coordinates

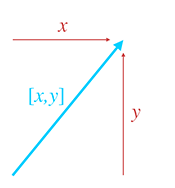

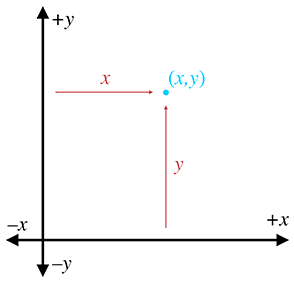

When we use Cartesian coordinates to describe vectors, each coordinate measures a signed

displacement in the corresponding dimension. For example, in 2D, we list the displacement

parallel to the

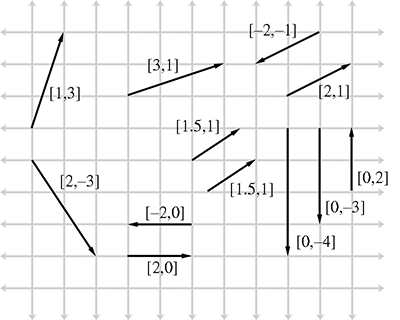

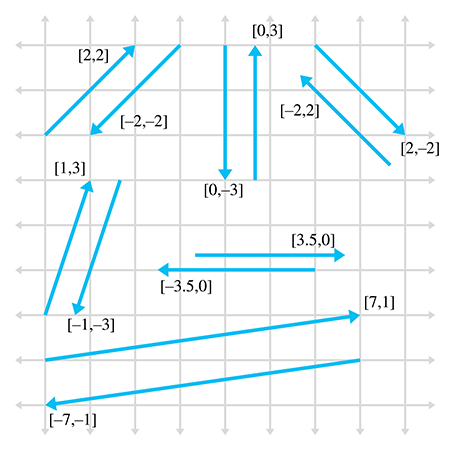

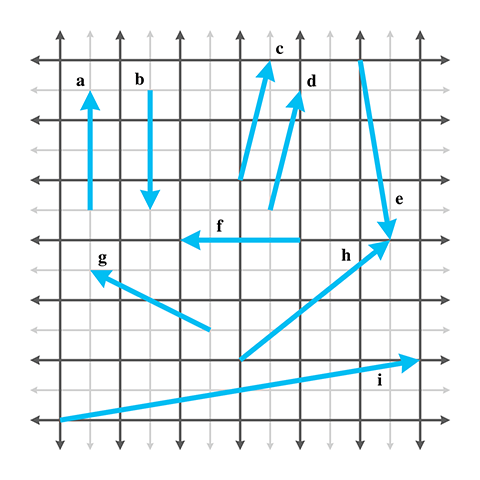

Figure 2.4 shows several 2D vectors and their values. Notice that the position of each vector on the diagram is irrelevant. (The axes are conspicuously

absent to emphasize this fact, although we do assume the standard convention of

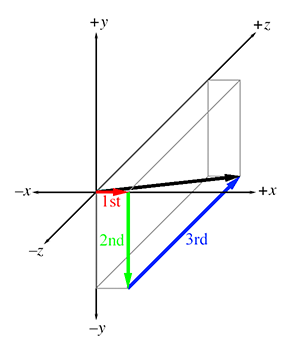

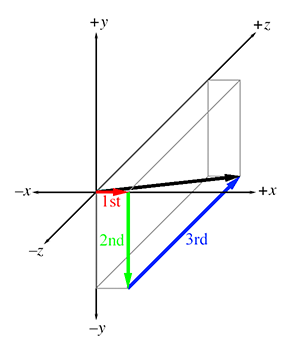

3D vectors are a simple extension of 2D vectors. A 3D vector

contains three numbers, which measure the signed displacements in

the

We are focusing on Cartesian coordinates for now, but they are not the only way to describe vectors mathematically. Polar coordinates are also common, especially in physics textbooks. Polar coordinates are the subject of Chapter 7.

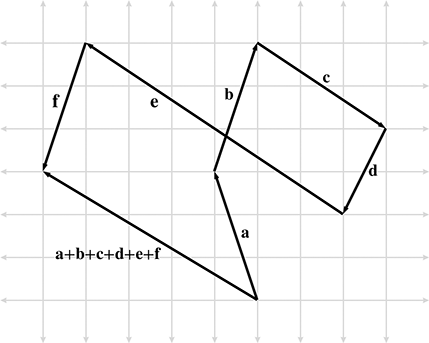

2.3.1Vector as a Sequence of Displacements

One helpful way to think about the displacement described by a vector is to break out the vector into its axially aligned components. When these axially aligned displacements are combined, they cumulatively define the displacement defined by the vector as a whole.

For example, the 3D vector

The order in which we perform the steps is not important; we could move 4 units forward, 3 units down, and then 1 unit to the right, and we would have displaced by the same total amount. The different orderings correspond to different routes along the axially aligned bounding box containing the vector. Section 2.7.2 mathematically verifies this geometric intuition.

2.3.2The Zero Vector

For any given vector dimension, there is a special vector, known as the zero vector, that

has zeroes in every position. For example, the 3D zero vector is

The zero vector is special because it is the only vector with a magnitude of zero. All other vectors have a positive magnitude. The zero vector is also unique because it is the only vector that does not have a direction.

Since the zero vector doesn't have a direction or length, we don't draw it as an arrow like we do for other vectors. Instead, we depict the zero vector as a dot. But don't let this make you think of the zero vector as a “point” because a vector does not define a location. Instead, think of the zero vector as a way to express the concept of “no displacement,” much as the scalar zero stands for the concept of “no quantity.”

Like the scalar zero you know, the zero vector of a given dimension is the additive

identity for the set of vectors of that dimension. Try to take yourself back to your algebra

class, and retrieve from the depths of your memory the concept of the additive identity: for any

set of elements, the additive identity of the set is the element

2.4Vectors versus Points

Recall that a “point” has a location but no real size or thickness. In this chapter, we have learned how a “vector” has magnitude and direction, but no position. So “points” and “vectors” have different purposes, conceptually: a “point” specifies a position, and a “vector” specifies a displacement.

But now examine Figure 2.6, which compares an illustration from Chapter 1 (Figure 1.8), showing how 2D points are located, with a figure from earlier in this chapter (Figure 2.3), showing how 2D vectors are specified. It seems that there is a strong relationship between points and vectors. This section examines this important relationship.

|

|

2.4.1Relative Position

Section 2.2 discussed the fact that because vectors can describe displacements, they can describe relative positions. The idea of a relative position is fairly straightforward: the position of something is specified by describing where it is in relation to some other, known location.

This begs the questions: Where are these “known” locations? What is an “absolute” position? It is surprising to realize that there is no such thing! Every attempt to describe a position requires that we describe it relative to something else. Any description of a position is meaningful only in the context of some (typically “larger”) reference frame. Theoretically, we could establish a reference frame encompassing everything in existence and select a point to be the “origin” of this space, thus defining the “absolute” coordinate space. However, even if such an absolute coordinate space were possible, it would not be practical. Luckily for us, absolute positions in the universe aren't important. Do you know your precise position in the universe right now? We don't know ours, either.3

2.4.2The Relationship between Points and Vectors

Vectors are used to describe displacements, and therefore they can describe relative positions. Points are used to specify positions. But we have just established in Section 2.4.1 that any method of specifying a position must be relative. Therefore, we must conclude that points are relative as well—they are relative to the origin of the coordinate system used to specify their coordinates. This leads us to the relationship between points and vectors.

Figure 2.7 illustrates how the point

As you can see, if we start at the origin and move by the amount

specified by the vector

This may seem obvious, but it is important to understand that points and vectors are conceptually distinct, but mathematically equivalent. This confusion between “points” and “vectors” can be a stumbling block for beginners, but it needn't be a problem for you. When you think of a location, think of a point and visualize a dot. When you think of a displacement, think of a vector and visualize an arrow.

In many cases, displacements are from the origin, and so the distinction between points and vectors will be a fine one. However, we often deal with quantities that are not relative to the origin, or any other point for that matter. In these cases, it is important to visualize these quantities as an arrow rather than a point.

The math we develop in the following sections operates on “vectors” rather than “points.” Keep in mind that any point can be represented as a vector from the origin.

Actually, now would be a good time to warn you that a lot of people take a much firmer stance on this issue and would not approve of our cavalier attitude in treating vectors and points as mathematical equals.4 Such hard-liners will tell you, for example, that while you can add two vectors (yielding a third vector), and you can add a vector and a point (yielding a point), you cannot add two points together. We admit that there is some value in understanding these distinctions in certain circumstances. However, we have found that, especially when writing code that operates on points and vectors, adherence to these ethics results in programs that are almost always longer and never faster.5 Whether it makes the code cleaner or easier to understand is a highly subjective matter. Although this book does not use different notations for points and vectors, in general it will be clear whether a quantity is a point or a vector. We have tried to avoid presenting results with vectors and points mixed inappropriately, but for all the intermediate steps, we might not have been quite as scrupulous.

2.4.3It's All Relative

Before we move on to the vector operations, let's take a brief philosophical intermission. Spatial position is not the only aspect of our world for which we have difficulty establishing an “absolute” reference, and so we use relative measurements. There are also temperature, loudness, and velocity.

Temperature. One of the first attempts to make

a standard temperature scale occurred about AD 170, when Galen

proposed a standard “neutral” temperature made up of equal

quantities of boiling water and ice. On either side of this

temperature were four degrees of “hotter” and four degrees of

“colder.” Sounds fairly primitive, right? In 1724, Gabriel

Fahrenheit suggested a bit more precise system. He suggested that

mercury be used as the liquid in a thermometer, and calibrated his

scale using two reference points: the freezing point of water, and

the temperature of a healthy human being. He called his scale the

Fahrenheit scale, and measurements were in °F. In

1745, Carolus Linnaeus of Uppsala, Sweden, suggested that things

would be simpler if we made the scale range from 0 (at the freezing

point of water) to 100 (water's boiling point), and called this scale the

centigrade scale. (This scale was later abandoned in favor

of the Celsius scale, which is technically different from

centigrade in subtle ways that are not important here.)

Notice that all of these scales are relative—they are based

on the freezing point of water, which is an arbitrary (but

highly practical) reference point. A temperature reading of

Loudness. Loudness is usually measured in

decibels (abbreviated dB). To be more precise,

decibels are used to measure the ratio of two

power levels. If we have two power levels

So, if

None of these values are absolute—but how could they be? How could your digital audio program know the absolute loudness you will experience, which depends not only on the audio data, but also the volume setting on your computer, the volume knob on your amplifier, the power supplied by the amplifier to your speakers, the distance you are from the speakers, and so on.

Sometimes people describe how loud something is in terms of an absolute dB number. Following in the footsteps of Gabriel Fahrenheit, this scale uses a reference point based on the human body. “Absolute” dB numbers are actually relative to the threshold of hearing for a normal human.6 Because of this, it's actually possible to have an “absolute” dB reading that is negative. This simply means that the intensity is below the threshold where most people are able to hear it.

At this point, we should probably mention that there is a way to devise an absolute scale for loudness, by measuring a physical quantity such as pressure, energy, or power, all of which have an absolute minimum value of zero. The point is that these absolute systems aren't used in many cases—the relative system is the one that's the most useful.

Velocity. How fast are you moving right now? Perhaps you're sitting in a comfy chair, so you'd say that your speed was zero. Maybe you're in a car and so you might say something like 65 mph. (Hopefully someone else is driving!) Actually, you are hurtling through space at almost 30 km per second! That's about the speed that Earth travels in order to make the 939-million-km trek around the sun each year. Of course, even this velocity is relative to the sun. Our solar system is moving around within the Milky Way galaxy. So then how fast are we actually moving, in absolute terms? Galileo told us back in the 17th century that this question doesn't have an answer—all velocity is relative.

Our difficulty in establishing absolute velocity is similar to the difficulty in establishing position. After all, velocity is displacement (difference between positions) over time. To establish an absolute velocity, we'd need to have some reference location that would “stay still” so that we could measure our displacement from that location. Unfortunately, everything in our universe seems to be orbiting something else.

2.5Negating a Vector

The previous sections have presented a high-level overview of vectors. The remainder of this chapter looks at specific mathematical operations we perform on vectors. For each operation, we first define the mathematical rules for performing the operation and then describe the geometric interpretations of the operation and give some practical uses for the operation.

The first operation we'd like to consider is that of vector negation. When discussing the zero

vector, we asked you to recall from group theory the idea of the additive identity. Please

go back to wherever it was in your brain that you found the additive identity, perhaps between

the metaphorical couch cushions, or at the bottom of a box full of decade-old tax forms. Nearby,

you will probably find a similarly discarded obvious-to-the-point-of-useless concept: the

additive inverse. Let's dust it off. For any group, the additive inverse of

The negation operation can be applied to vectors. Every vector

2.5.1Official Linear Algebra Rules

To negate a vector of any dimension, we simply negate each component of the vector. Stated formally,

Negating a vectorApplying this to the specific cases of 2D, 3D, and 4D vectors, we have

Negating 2D, 3D, and 4D vectorsA few examples are

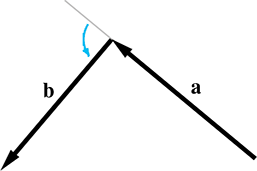

2.5.2Geometric Interpretation

Negating a vector results in a vector of the same magnitude but opposite direction, as shown in Figure 2.8.

Remember, the position of a vector on a diagram is irrelevant—only the magnitude and direction are important.

2.6Vector Multiplication by a Scalar

Although we cannot add a vector and a scalar, we can multiply a vector by a scalar. The result is a vector that is parallel to the original vector, with a different length and possibly opposite direction.

2.6.1Official Linear Algebra Rules

Vector-times-scalar multiplication is straightforward; we simply multiply each component of the vector by the scalar. Stated formally,

Multiplying a vector by a scalarApplying this rule to 3D vectors, as an example, we get

Multiplying a 3D vector by a scalar

Although the scalar and vector may be written in either order, most people choose to put the scalar

on the left, preferring

A vector may also be divided by a nonzero scalar. This is equivalent to multiplying by the reciprocal of the scalar:

Dividing a 3D vector by a scalar

Some examples are

Here are a few things to notice about multiplication of a vector by a scalar:

- When we multiply a vector and a scalar, we do not use any multiplication symbol. The multiplication is signified by placing the two quantities side-by-side (usually with the vector on the right).

-

Scalar-times-vector multiplication and division both occur before any

addition and subtraction. For example

- A scalar may not be divided by a vector, and a vector may not be divided by another vector.

-

Vector negation can be viewed as the special case of multiplying a

vector by the scalar

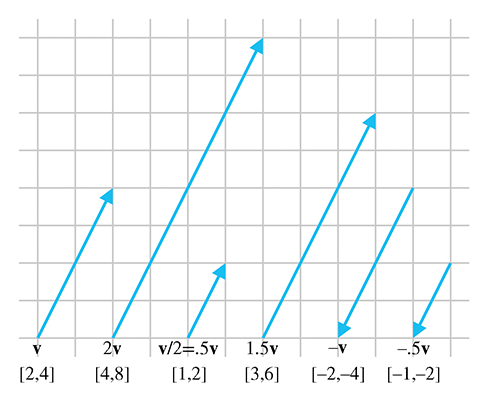

2.6.2Geometric Interpretation

Geometrically, multiplying a vector by a scalar

2.7Vector Addition and Subtraction

We can add and subtract two vectors, provided they are of the same dimension. The result is a vector quantity of the same dimension as the vector operands. We use the same notation for vector addition and subtraction as is used for addition and subtraction of scalars.

2.7.1Official Linear Algebra Rules

The linear algebra rules for vector addition are simple: to add two vectors, we add the corresponding components:

Adding two vectors

Subtraction can be interpreted as adding the negative, so

For example, given

then

A vector cannot be added or subtracted with a scalar, or with a vector of a different dimension. Also, just like addition and subtraction of scalars, vector addition is commutative,

whereas vector subtraction is anticommutative,

2.7.2Geometric Interpretation

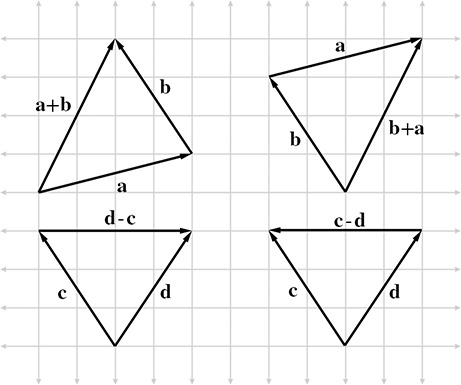

We can add vectors

Figure 2.10 provides geometric evidence that vector addition is commutative but

vector subtraction is not. Notice that the vector labeled

The triangle rule can be extended to more than two vectors. Figure 2.11 shows how the triangle rule verifies something we stated in Section 2.3.1: a vector can be interpreted as a sequence of axially aligned displacements.

Figure 2.12 is a reproduction of

Figure 2.5,

which shows how the vector

This seems obvious, but this is a very powerful concept. We will use a similar technique in Section 4.2 to transform vectors from one coordinate space to another.

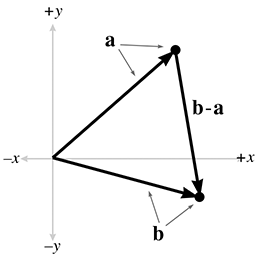

2.7.3Displacement Vector from One Point to Another

It is very common that we will need to compute the displacement from one point to another. In

this case, we can use the triangle rule and vector subtraction.

Figure 2.13 shows how the displacement vector from

As Figure 2.13 shows, to compute the vector from

Notice that the vector subtraction

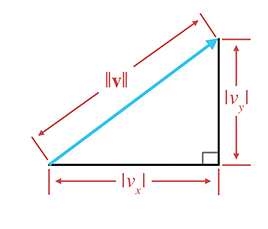

2.8Vector Magnitude (Length)

As we have discussed, vectors have magnitude and direction. However, you might have noticed that

neither the magnitude nor the direction is expressed explicitly in the vector (at least not when

we use Cartesian coordinates). For example, the magnitude of the 2D vector

2.8.1Official Linear Algebra Rules

In linear algebra, the magnitude of a vector is denoted by using double vertical bars surrounding

the vector. This is similar to the single vertical bar notation used for the absolute value

operation for scalars. This notation and the equation for computing the magnitude of a vector of

arbitrary dimension

Thus, the magnitude of a vector is the square root of the sum of the squares of the components of the vector. This sounds complicated, but the magnitude equations for 2D and 3D vectors are actually very simple:

Vector magnitude for 2D and 3D vectorsThe magnitude of a vector is a nonnegative scalar quantity. An example of how to compute the magnitude of a 3D vector is

One quick note to satisfy all you sticklers who already know about vector norms and at this

moment are pointing your web browser to gamemath.com, looking for the email address for errata. The

term norm actually has a very general definition, and basically any equation that meets a

certain set of criteria can call itself a norm. So to describe Equation (2.2)

as the equation for the vector norm is slightly misleading. To be more accurate, we

should say that Equation (2.2) is the equation for the 2-norm, which is

one specific way to calculate a norm. The 2-norm belongs to a class of norms known as the

2.8.2Geometric Interpretation

Let's try to get a better understanding of why Equation (2.3) works. For any

vector

Notice that to be precise we had to put absolute value signs around the components

The Pythagorean theorem states that for any right triangle, the square of the length of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the lengths of the other two sides. Applying this theorem to Figure 2.14, we have

Since

Then, by taking the square root of both sides and simplifying, we get

which is the same as Equation (2.3). The proof of the magnitude equation in 3D is only slightly more complicated.

For any positive magnitude

2.9Unit Vectors

For many vector quantities, we are concerned only with direction and not magnitude: “Which way am I facing?” “Which way is the surface oriented?” In these cases, it is often convenient to use unit vectors. A unit vector is a vector that has a magnitude of one. Unit vectors are also known as normalized vectors.

Unit vectors are also sometimes simply called normals; however, a warning is in order concerning terminology. The word “normal” carries with it the connotation of “perpendicular.” When most people speak of a “normal” vector, they are usually referring to a vector that is perpendicular to something. For example, a surface normal at a given point on an object is a vector that is perpendicular to the surface at that location. However, since the concept of perpendicular is related only to the direction of a vector and not its magnitude, in most cases you will find that unit vectors are used for normals instead of a vector of arbitrary length. When this book refers to a vector as a “normal,” it means “a unit vector perpendicular to something else.” This is common usage, but be warned that the word “normal” primarily means “perpendicular” and not “unit length.” Since it is so common for normals to be unit vectors, we will take care to call out any situation where a “normal” vector does not have unit length.

In summary, a “normalized” vector always has unit length, but a “normal” vector is a vector that is perpendicular to something and by convention usually has unit length.

2.9.1Official Linear Algebra Rules

For any nonzero vector

For example, to normalize the 2D vector

The zero vector cannot be normalized. Mathematically, this is not allowed because it would result in division by zero. Geometrically, it makes sense because the zero vector does not define a direction—if we normalized the zero vector, in what direction should the resulting vector point?

2.9.2Geometric Interpretation

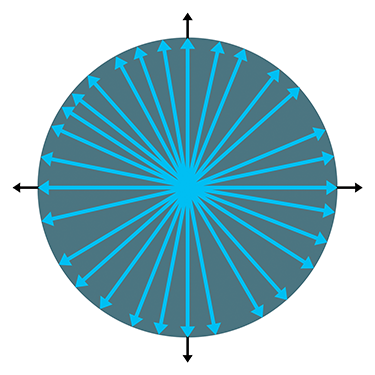

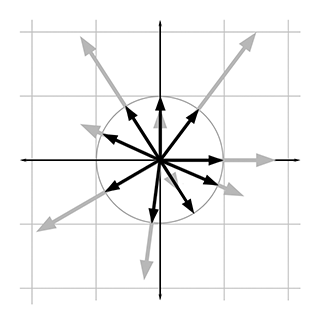

In 2D, if we draw a unit vector with the tail at the origin, the head of the vector will touch a unit circle centered at the origin. (A unit circle has a radius of 1.) In 3D, unit vectors touch the surface of a unit sphere. Figure 2.16 shows several 2D vectors of arbitrary length in gray, beneath their normalized counterparts in black.

Notice that normalizing a vector makes some vectors shorter (if their length was greater than 1) and some vectors longer (if their length was less than 1).

2.10The Distance Formula

We are now prepared to derive one of the oldest and most fundamental formulas in computational geometry: the distance formula. This formula is used to compute the distance between two points.

First, let's define distance as the length of the line segment between the two points. Since a

vector is a directed line segment, geometrically it makes sense that the distance between the two

points would be equal to the length of a vector from one point to the other. Let's derive the

distance formula in 3D. First, we will compute the vector

The distance between

Substituting for

Thus, we have derived the distance formula in 3D. The 2D equation is even simpler:

The 2D distance formulaLet's look at an example in 2D:

Notice that it doesn't matter which point we call

2.11Vector Dot Product

Section 2.6 showed how to multiply a vector by a scalar. We can also multiply two vectors together. There are two types of vector products. The first vector product is the dot product (also known as the inner product), the subject of this section. We talk about the other vector product, the cross product, in Section 2.12.

The dot product is ubiquitous in video game programming, useful in everything from graphics, to simulation, to AI. Following the pattern we used for the operations, we first discuss the algebraic rules for computing dot products in Section 2.11.1, followed by some geometric interpretations in Section 2.11.2.

The dot product formula is one of the few formulas in this book worth memorizing. First of all, it's really easy to memorize. Also, if you understand what the dot product does, the formula makes sense. Furthermore, the dot product has important relationships to many other operations, such as matrix multiplication, convolution of signals, statistical correlations, and Fourier transforms. Understanding the formula will make these relationships more apparent.

Even more important than memorizing a formula is to get an intuitive grasp for what the dot product does. If there is only enough space in your brain for either the formula or the geometric definition, then we recommend internalizing the geometry, and getting the formula tattooed on your hand. You need to understand the geometric definition in order to use the dot product. When programming in computer languages such as C++, HLSL, or even Matlab and Maple, you won't need to know the formula anyway, since you will usually tell the computer to do a dot product calculation not by typing in the formula, but by invoking a high-level function or overloaded operator. Furthermore, the geometric definition of the dot product does not assume any particular coordinate frame or even the use of Cartesian coordinates.

2.11.1Official Linear Algebra Rules

The name “dot product” comes from the dot symbol used in the notation:

The dot product of two vectors is the sum of the products of corresponding components, resulting in a scalar:

Vector dot productThis can be expressed succinctly by using the summation notation

Dot product using summation notationApplying these rules to the 2D and 3D cases yields

2D and 3D dot productsExamples of the dot product in 2D and 3D are

It is obvious from inspection of the equations that vector dot product is commutative:

2.11.2Geometric Interpretation

Now let's discuss the more important aspect of the dot product: what it means geometrically. It would be difficult to make too big of a deal out of the dot product, as it is fundamental to almost every aspect of 3D math. Because of its supreme importance, we're going to dwell on it a bit. We'll discuss two slightly different ways of thinking about this operation geometrically; since they are really equivalent, you may or may not think one interpretation or the other is “more fundamental,” or perhaps you may think we are being redundant and wasting your time. You might especially think this if you already have some exposure to the dot product, but please indulge us.

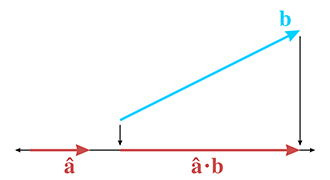

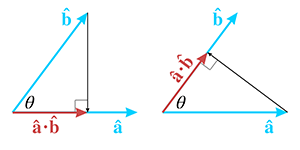

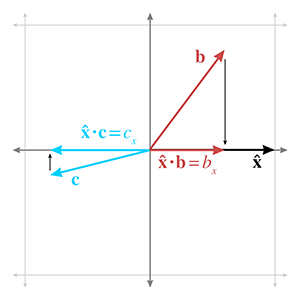

The first geometric definition to present is perhaps the less common of the two, but in agreement with the advice of Dray and Manogue [1], we believe it's actually the more useful. The interpretation we first consider is that of the dot product performing a projection.

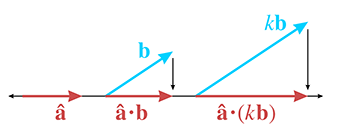

Assume for the moment that

(Remember that vectors are displacements and do not have a fixed

position, so we are free to move them around on a diagram anywhere we wish.) We can define the dot

product

We have drawn the projections as arrows, but remember that the result of a dot product is a scalar, not a vector. Still, when you first learned about negative numbers, your teacher probably depicted numbers as arrows on a number line, to emphasize their sign, just as we have. After all, a scalar is a perfectly valid one-dimensional vector.

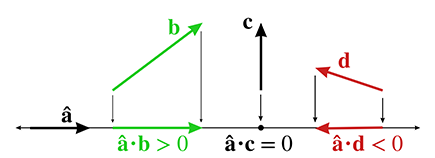

What does it mean for the dot product to measure a signed length? It means the value will

be negative when the projection of

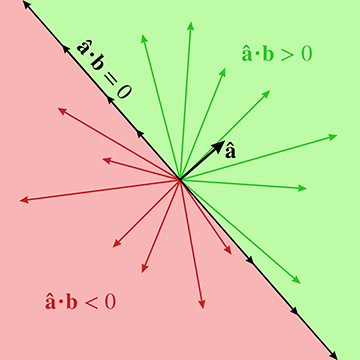

In other words, the sign of the dot product can give us a rough classification of the relative

directions of the two vectors. Imagine a line (in 2D) or plane (in 3D) perpendicular to the

vector

Next, consider what happens when we scale

Let's state this fact algebraically and prove it by using the formula:

Dot product is associative with multiplication by a scalarThe expanded scalar math in the middle uses three dimensions as our example, but the vector notation at either end of the equation applies for vectors of any dimension.

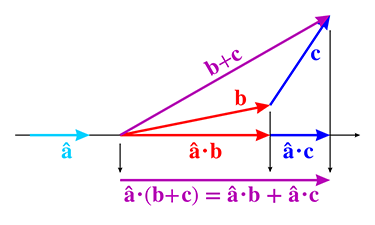

We've seen what happens when we scale

So scaling

As we continue to examine the properties of the dot product, some will be easiest to illustrate

geometrically when either

You may well wonder why the dot product measures the projection of the second operand onto the

first, and not the other way around. When the two vectors

We've already shown how scaling either vector will scale the dot product proportionally, so this

result applies for

The next important property of the dot product is that it distributes over addition and subtraction, just like scalar multiplication. This time let's do the algebra before the geometry. When we say that the dot product “distributes,” that means that if one of the operands to the dot product is a sum, then we can take the dot product of the pieces individually, and then take their sum. Switching back to three dimensions for our example,

Dot product distributes over addition and subtraction

By replacing

Now let's look at a special situation in which one of the vectors is the unit vector pointing in

the

If we combine this “sifting” property of the dot product with the fact that it distributes over addition, which we have been able to show in purely geometric terms, we can see why the formula has to be what it is.

Because the dot product measures the length of a projection, it has an interesting relationship

to the vector magnitude calculation. Remember that the vector magnitude is a scalar measuring

the amount of displacement (the length) of the vector. The dot product also measures the amount

of displacement, but only the displacement in a particular direction is counted;

perpendicular displacement is discarded by the projecting process. But what if we measure the

displacement in the same direction that the vector is pointing? In this case, all of the

vector's displacement is in the direction being measured, so if we project a vector onto itself,

the length of that projection is simply the magnitude of the vector. But remember that

Before we switch to the second interpretation of the dot product, let's check out one more very

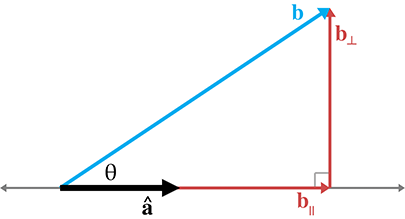

common use of the dot product as a projection. Assume once more that

We've already established that the length of

Once we know

It's not too difficult to generalize these results to the case where

In the rest of this book, we make use of these equations several times to separate a vector into components that are parallel and perpendicular to another vector.

Now let's examine the dot product through the lens of trigonometry. This is the more common geometric interpretation of the dot product, which places a bit more emphasis on the angle between the vectors. We've been thinking in terms of projections, so we haven't had much need for this angle. Less experienced and conscientious authors [2] might give you just one of the two important viewpoints, which is probably sufficient to interpret an equation that contains the dot product. However, a more valuable skill is to recognize situations for which the dot product is the correct tool for the job; sometimes it helps to have other interpretations pointed out, even if they are “obviously” equivalent to each other.

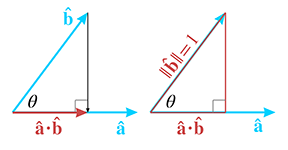

Consider the right triangle on the right-hand side of Figure 2.25. As the

figure shows, the length of the hypotenuse is 1 (since

In other words, the dot product of two unit vectors is equal to the cosine of the angle between

them. This statement is true even if the right triangle in Figure 2.25

cannot be formed, when

By combining these ideas with the previous observation that scaling either vector scales the dot product by the same factor, we arrive at the general relationship between the dot product and the cosine.

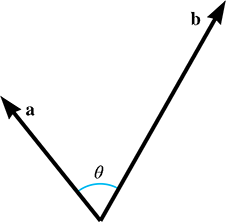

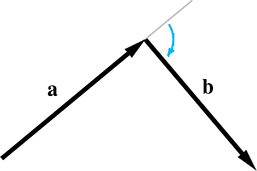

What does it mean to measure the angle between two vectors in 3D? Any two vectors will always lie

in a common plane (place them tail to tail to see this), and so we measure the angle in the plane

that contains both vectors. If the vectors are parallel, the plane is not unique, but the angle is

either

The dot product provides a way for us to compute the angle between two vectors. Solving

Equation (2.4) for

We can avoid the division in Equation (2.5) if we know that

If we do not need the exact value of

| Angle is | |||

| acute | pointing mostly in the same direction | ||

| right | perpendicular | ||

| obtuse | pointing mostly in the opposite direction |

Since the magnitude of the vectors does not affect the sign of the dot product,

Table 2.1 applies regardless of the lengths of

Let's summarize the dot product's geometric properties.

-

The dot product

- The dot product can be used to measure displacement in a particular direction.

-

The projection operation is closely related to the cosine function. The dot product

We review the commutative and distributive properties of the dot product at the end of this chapter along with other algebraic properties of vector operations.

2.12Vector Cross Product

The other vector product, known as the cross product, can be applied only in 3D. Unlike the dot product, which yields a scalar and is commutative, the vector cross product yields a 3D vector and is not commutative.

2.12.1Official Linear Algebra Rules

Similar to the dot product, the term “cross” product comes from the symbol used in the notation

For example,

The cross product enjoys the same level of operator precedence as the dot product: multiplication

occurs before addition and subtraction. When dot product and cross product are used together, the

cross product takes precedence:

As mentioned earlier, the vector cross product is not commutative. In fact, it is

anticommutative:

2.12.2Geometric Interpretation

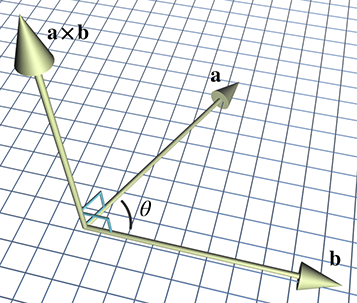

The cross product yields a vector that is perpendicular to the original two vectors, as illustrated in Figure 2.27.

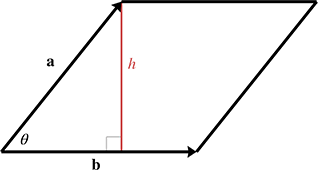

The length of

As it turns out, this is also equal to the area of the parallelogram formed with two sides

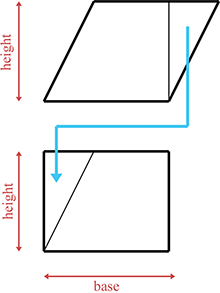

First, from planar geometry, we know that the area of the parallelogram is

The area of a rectangle is given by its length and width. In this case, this area is the product

Returning to Figure 2.28, let

If

We have stated that

| Clockwise turn | Counterclockwise turn |

|

|

|

In a left-handed coordinate system,

|

In a left-handed coordinate system, |

Figure 2.30 shows clockwise and counterclockwise turns. Notice that to make the clockwise or counterclockwise determination, we must align the

head of

Let's apply this general rule to the specific case of the cardinal axes. Let

You can also remember which way the cross product points by

using your hand, similar to the way we distinguished between left-handed and right-handed

coordinate spaces in Section 1.3.3. Since we're using a left-handed

coordinate space in this book, we'll show how it's done using your left hand. Let's say you have

two vectors,

Of course, a similar trick works with your right hand for right-handed coordinate spaces.

One of the most important uses of the cross product is to create a vector that is perpendicular to a plane (see Section 9.5), triangle (Section 9.6), or polygon (Section 9.7).

2.13Linear Algebra Identities

The Greek philosopher Arcesilaus reportedly said, “Where you find the laws most numerous, there you will find also the greatest injustice.” Well, nobody said vector algebra was fair. Table 2.2 lists some vector algebra laws that are occasionally useful but should not be memorized. Several identities are obvious and are listed for the sake of completeness; all of them can be derived from the definitions given in earlier sections.

| Identity | Comments |

| Commutative property of vector addition | |

| Definition of vector subtraction | |

| Associative property of vector addition | |

| Associative property of scalar multiplication | |

| Scalar multiplication distributes over vector addition | |

| Multiplying a vector by a scalar scales the magnitude by a factor equal to the absolute value of the scalar | |

| The magnitude of a vector is nonnegative | |

| The Pythagorean theorem applied to vector addition. | |

| Triangle rule of vector addition. (No side can be longer than the sum of the other two sides.) | |

| Commutative property of dot product | |

| Vector magnitude defined using dot product | |

|

|

Associative property of scalar multiplication with dot product |

|

|

Dot product distributes over vector addition and subtraction |

| The cross product of any vector with itself is the zero vector. (Because any vector is parallel with itself.) | |

| Cross product is anticommutative. | |

| Negating both operands to the cross product results in the same vector. | |

|

|

Associative property of scalar multiplication with cross product. |

|

|

Cross product distributes over vector addition and subtraction. |

Exercises

-

Let

-

Identify

-

Compute

-

Identify

-

Identify the quantities in each of the following sentences as scalar or vector.

For vector quantities, give the magnitude and direction. (Note: some directions

may be implicit.)

- How much do you weigh?

- Do you have any idea how fast you were going?

- It's two blocks north of here.

- We're cruising from Los Angeles to New York at 600 mph, at an altitude of 33,000 ft.

-

Give the values of the following vectors. The darker grid lines represent one unit.

-

Identify the following statements as true or false. If the statement is

false, explain why.

- The size of a vector in a diagram doesn't matter; we just need to draw it in the right place.

- The displacement expressed by a vector can be visualized as a sequence of axially aligned displacements.

- These axially aligned displacements from the previous question must occur in order.

-

The vector

-

Evaluate the following vector expressions:

-

-

Normalize the following vectors:

-

-

Evaluate the following vector expressions:

-

-

Compute the distance between the following pairs of points:

-

-

Evaluate the following vector expressions:

-

-

Given the two vectors

separate

-

Use the geometric definition of the dot product

to prove the law of cosines.

-

Use trigonometric identities and the algebraic definition of the dot product in 2D

to prove the geometric interpretation of the dot product in 2D. (Hint: draw a diagram of the vectors and all angles involved.)

-

Calculate

-

-

Prove the equation for the magnitude of the cross product

(Hint: make use of the geometric interpretation of the dot product and try to show how the left and right sides of the equation are equivalent, rather than trying to derive one side from the other.)

-

Section 2.8 introduced the norm of a vector, namely, a scalar value associated with a given vector.

However, the definition of the norm given in that section is not the only definition of a norm for a vector. In general,

the

-

The

-

The

-

The infinity norm, a.k.a. Chebyshev norm (

-

(a)For each of the following find

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- (1)

-

*(b)Draw the unit circle (i.e., the set of all vectors with

-

The

- A man is boarding a plane. The airline has a rule that no carry-on item may be more than two feet long, two feet wide, or two feet tall. He has a very valuable sword that is three feet long, yet he is able to carry the sword on board with him.9 How is he able to do this? What is the longest possible item that he could carry on?

- Verify Figure 2.11 numerically.

- Is the coordinate system used in Figure 2.27 a left-handed or right-handed coordinate system?

-

One common way of defining a bounding box for a 2D object is to specify a

center point

-

Describe the four corners

- Describe the eight corners of a bounding cube, extending this idea into 3D.

-

Describe the four corners

-

A nonplayer character (NPC) is standing at location

-

How can the dot product be used to determine whether the point

-

Let

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

- (7)

- (1)

-

How can the dot product be used to determine whether the point

-

Extending the concept from Exercise 20, consider the case where the NPC

has a limited field of view (FOV). If the total FOV angle is

-

How can the dot product be used to determine whether the point

-

For each of the points

- Suppose that the NPC's viewing distance is also limited to a maximum distance of 7 units. Which points are visible to the NPC then?

-

How can the dot product be used to determine whether the point

-

Consider three points labeled

-

How can the cross product be used to determine whether, when moving from

-

For each of the following sets of three points, determine whether the NPC

is turning clockwise or counterclockwise when moving from

-

(1)

-

(2)

-

(3)

-

(4)

-

(1)

-

How can the cross product be used to determine whether, when moving from

-

In the derivation of a matrix to scale along an

arbitrary axis, we reach a step where we have the vector expression

where

-

A similar problem arises with the derivation of a matrix to rotate about an arbitrary

axis. Given an arbitrary scalar

- But the perspective taken by physics textbooks is probably the one that's more appropriate for video game programming, at least in the beginning.

- The typeface used here is not intended to limit the discussion to the set of scalars. We are talking about elements in any set. Also, we request leniency from the abstract algebra sticklers for our use of the word “set,” when we should use “group.” But the latter term is not as widely understood, and we could only afford this footnote to dwell on the distinction.

- But we do know our position relative to the nearest Taco Bell.

- If you are one of those people, then this is a warning of a slightly different sort!

- Indeed, sometimes slower, depending on your compiler.

- About 20 micropascals. However, this number varies with frequency. It also increases with age. One author remembers that when he was young, his father would never turn the radio in the car completely off, but rather would turn the volume down below the (father's) threshold of hearing. The son's threshold of hearing was just low enough for this to be irritating. Today the son owns his own car and car radio, and has realized, with some degree of embarrassment, that he also often turns the radio volume down without turning it off. However, he offers in his defense that he turns it all the way down, below everyone's threshold of hearing. (The other author wishes to suggest that clearly even the term “normal human” is relative.)

-

One notation you will probably bump up against is treating the

dot product as an ordinary matrix multiplication, denoted by

- Thus shirking our traditional duties as mathematics authors to make intuitive concepts sound much more complicated than they are.

- Please ignore the fact that nowadays this could never happen for security reasons. You can think of this exercise as taking place in a Quentin Tarantino movie.