Chapter 4 investigated some of the basic mathematical properties of matrices. It also developed a geometric understanding of matrices and their relationship to coordinate space transformations in general. This chapter continues our investigation of transformations.

To be more specific, this chapter is concerned with expressing linear transformations in

3D using

This chapter discusses the implementation of linear transformations via matrices. It is divided roughly into two parts. In the first part, Sections 5.1–5.5, we take the basic tools from previous chapters to derive matrices for primitive linear transformations of rotation, scaling, orthographic projection, reflection, and shearing. For each transformation, examples and equations in 2D and 3D are given. The same strategy will be used repeatedly: determine what happens to the standard basis vectors as a result of the transformation and then put those transformed basis vectors into the rows of our matrix. Note that these discussions assume an active transformation: the object is transformed while the coordinate space remains stationary. Remember from Section 3.3.1 that we can effectively perform a passive transformation (transform the coordinate space and keep the object still) by transforming the object by the oppositeamount.

A lot of this chapter is filled with messy equations and details, so you might be tempted to skip over it—but don't! There are a lot of important, easily digested principles interlaced with the safely forgotten details. We think it's important to be able to understand how various transform matrices can be derived, so in principle you can derive them on your own from scratch. Commit the high-level principles in this chapter to memory, and don't get too bogged down in the details. This book will not self-destruct after you read it, so keep it on hand for reference when you need a particular equation.

The second part of this chapter returns to general principles of transformations. Section 5.6 shows how a sequence of primitive transformations may be combined by using matrix multiplication to form a more complicated transformation. Section 5.7 discusses various interesting categories of transformations, including linear, affine, invertible, angle-preserving, orthogonal, and rigid-body transforms.

5.1Rotation

We have already seen general examples of rotation matrices. Now let's develop a more rigorous definition. First, Section 5.1.1 examines 2D rotation. Section 5.1.2 shows how to rotate about a cardinal axis. Finally, Section 5.1.3 tackles the most general case of rotation about an arbitrary axis in 3D.

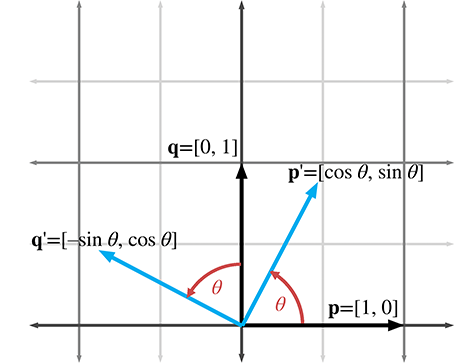

5.1.1Rotation in 2D

In 2D, there's really only one type of rotation that we can do: rotation about

a point. This chapter is concerned with linear transformations, which do not contain translation,

so we restrict our discussion even further to rotation about the origin. A 2D rotation about the

origin has only one parameter, the angle

Now that we know the values of the basis vectors after rotation, we can build our matrix:

2D rotation matrix

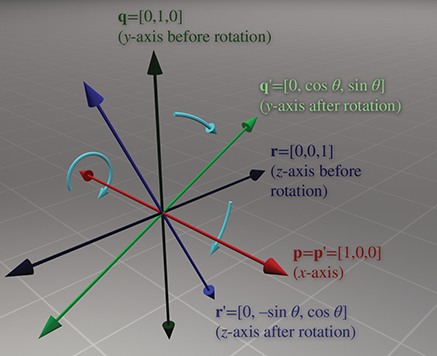

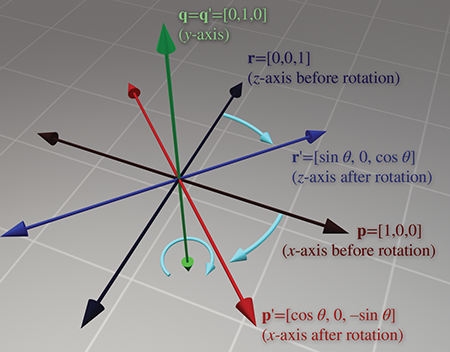

5.1.23D Rotation about Cardinal Axes

In 3D, rotation occurs about an axis rather than a point, with the term axis taking

on its more commonplace meaning of a line about which something rotates. An axis of rotation

does not necessarily have to be one of the cardinal

in this section. Again, we are not considering translation in this chapter, so we will limit the discussion to rotation about an axis that passes through the origin. In any case, we'll need to establish which direction of rotation is considered “positive” and which is considered “negative.” We're going to obey the left-hand rule for this. Review Section 1.3.3 if you've forgotten this rule.

Let's start with rotation about the

Rotation about the

And finally, rotation about the

Please note that although the figures in this section use a left-handed convention, the matrices work in either left- or right-handed coordinate systems, due to the conventions used to define the direction of positive rotation. You can verify this visually by looking at the figures in a mirror.

5.1.33D Rotation about an Arbitrary Axis

We can also rotate about an arbitrary axis in 3D, provided, of course, that the axis passes

through the origin, since we are not considering translation at the moment. This is more

complicated and less common than rotating about a cardinal axis. As before, we define

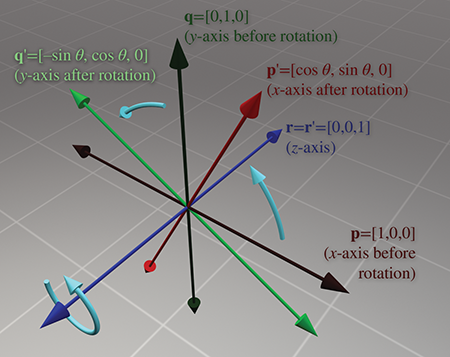

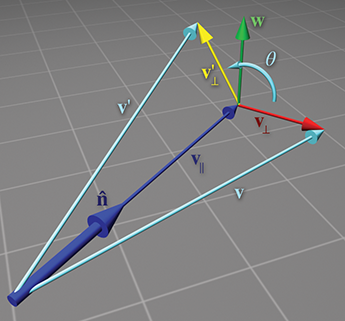

Let's derive a matrix to rotate about

To derive the matrix

-

The vector

-

The vector

-

The vector

These vectors are shown in Figure 5.5.

How do these vectors help us compute

Let's summarize the vectors we have computed:

Substituting for

Equation (5.1) allows us to rotate any arbitrary vector about any arbitrary axis. We could perform arbitrary rotation transformations armed only with this equation, so in a sense we are done—the remaining arithmetic is essentially a notational change that expresses Equation (5.1) as a matrix multiplication.

Now that we have expressed

Note that

Constructing the matrix from these basis vectors, we get

3D matrix to rotate about an arbitrary axis5.2Scale

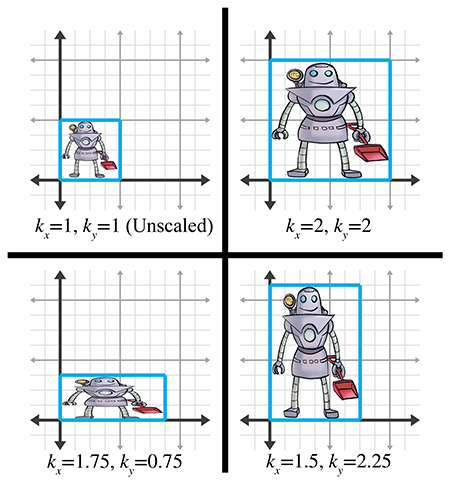

We can scale an object to make it proportionally bigger or smaller by a factor of

If we wish to “stretch” or “squash” the object, we can apply different scale factors in different directions, resulting in nonuniform scale. Nonuniform scale does not preserve angles. Lengths, areas, and volumes are adjusted by a factor that varies according to the orientation relative to the direction of scale.

If

Section 5.2.1 begins with the simple case of scaling along the cardinal axes. Then Section 5.2.2 examines the general case, scaling along an arbitrary axis.

5.2.1Scaling along the Cardinal Axes

The simplest scale operation applies a separate scale factor along each cardinal axis. The scale along an axis is applied about the perpendicular axis (in 2D) or plane (in 3D). If the scale factors for all axes are equal, then the scale is uniform; otherwise, it is nonuniform.

In 2D, we have two scale factors,

As is intuitively obvious, the basis vectors

Constructing the 2D scale matrix

For 3D, we add a third scale factor

If we multiply any arbitrary vector by this matrix, then, as expected, each component is scaled by the appropriate scale factor:

5.2.2Scaling in an Arbitrary Direction

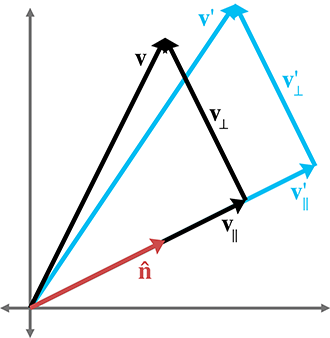

We can apply scale independent of the coordinate system used by scaling in an arbitrary

direction. We define

To derive a matrix that scales along an arbitrary axis, we'll use an approach similar to the one

used in Section 5.1.3 for rotation about an arbitrary axis. Let's

derive an expression that, given an arbitrary vector

Summarizing the known vectors and substituting gives us

Now that we know how to scale an arbitrary vector, we can compute the value of the basis vectors after scale. We derive the first 2D basis vector; the other basis vector is similar, and so we merely present the results. (Note that column vectors are used in the equations below strictly to make the equations format nicely on the page.):

Forming a matrix from the basis vectors, we arrive at the 2D matrix to scale by a factor of

In 3D, the values of the basis vectors are computed by

A suspicious reader wondering if we just made that up can step through the derivation in Exercise 2.23.

Finally, the 3D matrix to scale by a factor of

5.3Orthographic Projection

In general, the term projection refers to any dimension-reducing operation. As we discussed in Section 5.2, one way we can achieve projection is to use a scale factor of zero in a direction. In this case, all the points are flattened or projected onto the perpendicular axis (in 2D) or plane (in 3D). This type of projection is an orthographic projection, also known as a parallel projection, since the lines from the original points to their projected counterparts are parallel. We present another type of projection, perspective projection, in Section 6.5.

First, Section 5.3.1 discusses orthographic projection onto a cardinal axis or plane, and then Section 5.3.2 examines the general case.

5.3.1Projecting onto a Cardinal Axis or Plane

The simplest type of projection occurs when we project onto a cardinal axis (in 2D) or plane (in 3D). This is illustrated in Figure 5.8.

Projection onto a cardinal axis or plane most frequently occurs not by actual transformation, but

by simply discarding one of the coordinates while assigning the data into a variable of lesser

dimension. For example, we may turn a 3D object into a 2D object by discarding the

However, we can also project onto a cardinal axis or plane by using a scale value of zero on the perpendicular axis. For completeness, we present the matrices for these transformations:

Projecting onto a cardinal axis5.3.2Projecting onto an Arbitrary Line or Plane

We can also project onto any arbitrary line (in 2D) or plane (in 3D). As before, since we are

not considering translation, the line or plane must pass through the origin. The projection will

be defined by a unit vector

We can derive the matrix to project in an arbitrary direction by applying a zero scale factor along this direction, using the equations we developed in Section 5.2.2. In 2D, we have

2D matrix to project onto an arbitrary line

Remember that

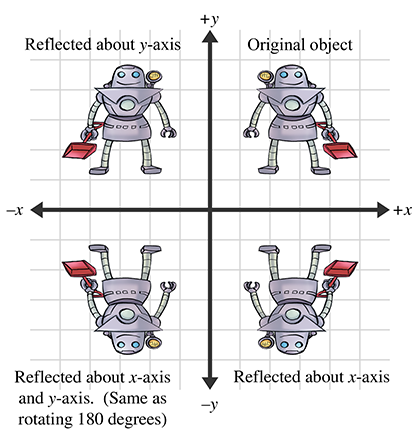

5.4Reflection

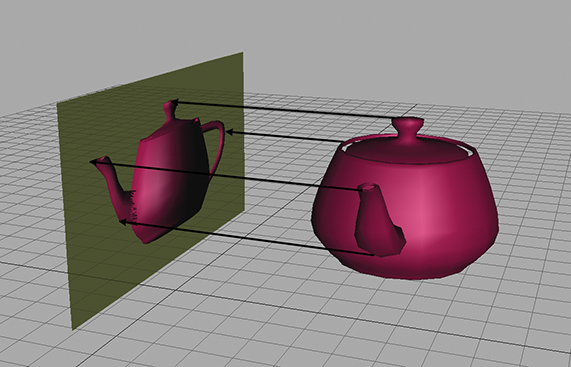

Reflection (also called mirroring) is a transformation that “flips” the object about a

line (in 2D) or a plane (in 3D). Figure 5.9 shows the result of reflecting an

object about the

Reflection can be accomplished by applying a scale factor of

In 3D, we have a reflecting plane instead of axis. For the transformation to be linear, the plane must contain the origin, in which case the matrix to perform the reflection is

Notice that an object can be “reflected” only once. If we reflect it again (even about a different axis or plane) then the object is flipped back to “right side out,” and it is the same as if we had rotated the object from its initial position. An example of this is shown in the bottom-left corner of Figure 5.9.

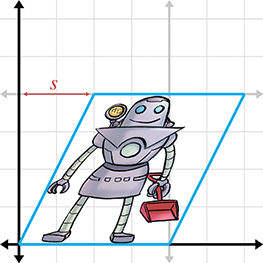

5.5Shearing

Shearing is a transformation that “skews” the coordinate space, stretching it nonuniformly.

Angles are not preserved; however, surprisingly, areas and volumes are. The basic idea is to add

a multiple of one coordinate to the other. For example, in 2D, we might take a multiple of

The matrix that performs this shear is

where the notation

In 3D, we can take one coordinate and add different multiples of that coordinate to the other two

coordinates. The notation

Shearing is a seldom-used transform. It is also known as a skew transform. Combining shearing and scaling (uniform or nonuniform) creates a transformation that is indistinguishable from a transformation containing rotation and nonuniform scale.

5.6Combining Transformations

This section shows how to take a sequence of transformation matrices and combine (or

concatenate) them into one single transformation matrix. This new matrix represents the

cumulative result of applying all of the original transformations in order. It's actually quite

easy. The transformation that results from applying the transformation with matrix

One very common example of this is in rendering. Imagine there is an object at an arbitrary

position and orientation in the world. We wish to render this object given a camera in any

position and orientation. To do this, we must take the vertices of the object (assuming we are

rendering some sort of triangle mesh) and transform them from object space into world space. This

transform is known as the model transform, which we denote

From Section 4.1.6, we know that matrix multiplication is associative, and so we could compute one matrix to transform directly from object to camera space:

Thus, we can concatenate the matrices outside the vertex loop, and have only one matrix multiplication inside the loop (remember there are many vertices):

So we see that matrix concatenation works from an algebraic perspective by using the associative

property of matrix multiplication. Let's see if we can get a more geometric interpretation of

what's going on. Recall from Section 4.2, our breakthrough

discovery, that the rows of a matrix contain the result of transforming the standard basis

vectors. This is true even in the case of multiple transformations. Notice that in the matrix

product

This explicitly shows that the rows of the product of

5.7Classes of Transformations

We can classify transformations according to several criteria. This section discuss classes of transformations. For each class, we describe the properties of the transformations that belong to that class and specify which of the primitive transformations from Sections 5.1 through 5.5 belong to that class. The classes of transformations are not mutually exclusive, nor do they necessarily follow an “order” or “hierarchy,” with each one more or less restrictive than the next.

When we discuss transformations in general, we may make use of the synonymous terms mapping

or function. In the most general sense, a mapping is simply a rule that takes an input and

produces an output. We denote that the mapping

This section also mentions the determinant of a matrix. We're getting a bit ahead of ourselves here, since a full explanation of determinants isn't given until Section 6.1. For now, just know that the determinant of a matrix is a scalar quantity that is very useful for making certain high-level, shall we say, determinations about the matrix.

5.7.1Linear Transformations

We met linear functions informally in Section 4.2.

Mathematically, a mapping

This is a fancy way of stating that the mapping

There are two important implications of this definition of linear

transformation. First, the mapping

and

Matrix multiplication satisfies Equation (5.3)In other words:

Second, any linear transformation will transform the zero vector

into the zero vector. If

Since all of the transformations we discussed in Sections 5.1 through 5.5 can be expressed using matrix multiplication, they are all linear transformations.

In some literature, a linear transformation is defined as one in which parallel lines remain parallel after transformation. This is almost completely accurate, with two exceptions. First, parallel lines remain parallel after translation, but translation is not a linear transformation. Second, what about projection? When a line is projected and becomes a single point, can we consider that point “parallel” to anything? Excluding these technicalities, the intuition is correct: a linear transformation may “stretch” things, but straight lines are not “warped” and parallel lines remain parallel.

5.7.2Affine Transformations

An affine transformation is a linear transformation followed by translation. Thus, the set of affine transformations is a superset of the set of linear transformations: any linear transformation is an affine translation, but not all affine transformations are linear transformations.

Since all of the transformations discussed in this chapter are linear transformations, they are all

also affine transformations (though none of them have a translation portion). Any transformation

of the form

5.7.3Invertible Transformations

A transformation is invertible if there exists an opposite transformation, known as the

inverse of

for all

There are nonaffine invertible transformations, but we will not consider them for the moment. For now, let's concentrate on determining if an affine transformation is invertible. As already stated, an affine transformation is a linear transformation followed by a translation. Obviously, we can always “undo” the translation portion by simply translating by the opposite amount. So the question becomes whether the linear transformation is invertible.

Intuitively, we know that all of the transformations other than projection can be “undone.” If we rotate, scale, reflect, or skew, we can always “unrotate,” “unscale,” “unreflect,” or “unskew.” But when an object is projected, we effectively discard one or more dimensions' worth of information, and this information cannot be recovered. Thus, all of the primitive transformations other than projection are invertible.

Since any linear transformation can be expressed as multiplication by a matrix, finding the inverse of a linear transformation is equivalent to finding the inverse of a matrix. We discuss how to do this in Section 6.2. If the matrix has no inverse, we say that it is singular, and the transformation is noninvertible. The determinant of an invertible matrix is nonzero.

In a nonsingular matrix, the zero vector is the only input vector that is mapped to the zero vector in the output space; all other vectors are mapped to some other nonzero vector. In a singular matrix, however, there exists an entire subspace of the input vectors, known as the null space of the matrix, that is mapped to the zero vector. For example, consider a matrix that projects orthographically onto a plane containing the origin. The null space of this matrix consists of the line of vectors perpendicular to the plane, since they are all mapped to the origin.

When a square matrix is singular, its basis vectors are not linearly independent (see

Section 3.3.3). If the basis vectors are linearly independent, then

they have full rank, and coordinates of any given vector in the span are uniquely determined. If

the vectors are linearly dependent, then there is a portion of the full

5.7.4Angle-Preserving Transformations

A transformation is angle-preserving if the angle between two vectors is not altered in either magnitude or direction after transformation. Only translation, rotation, and uniform scale are angle-preserving transformations. An angle-preserving matrix preserves proportions. We do not consider reflection an angle-preserving transformation because even though the magnitude of angle between two vectors is the same after transformation, the direction of angle may be inverted. All angle-preserving transformations are affine and invertible.

5.7.5Orthogonal Transformations

Orthogonal is a term that is used to describe a matrix whose rows form an orthonormal basis. Remember from Section 3.3.3 that the basic idea is that the axes are perpendicular to each other and have unit length. Orthogonal transformations are interesting because it is easy to compute their inverse and they arise frequently in practice. We talk more about orthogonal matrices in Section 6.3.

Translation, rotation, and reflection are the only orthogonal transformations. All orthogonal transformations are affine and invertible. Lengths, angles, areas, and volumes are all preserved; however in saying this, we must be careful as to our precise definition of angle, area, and volume, since reflection is an orthogonal transformation and we just got through saying in the previous section that we didn't consider reflection to be an angle-preserving transformation. Perhaps we should be more precise and say that orthogonal matrices preserve the magnitudes of angles, areas, and volumes, but possibly not the signs.

As Chapter 6 shows, the determinant of an orthogonal matrix is

5.7.6Rigid Body Transformations

A rigid body transformation is one that changes the location and orientation of an object, but not its shape. All angles, lengths, areas, and volumes are preserved. Translation and rotation are the only rigid body transformations. Reflection is not considered a rigid body transformation.

Rigid body transformations are also known as proper transformations. All rigid body transformations are orthogonal, angle-preserving, invertible, and affine. Rigid body transforms are the most restrictive class of transforms discussed in this section, but they are also extremely common in practice.

The determinant of any rigid body transformation matrix is 1.

5.7.7Summary of Types of Transformations

Table 5.1 summarizes the various classes of transformations. In this table, a Y means that the transformation in that row always has the property associated with that column. The absence of a Y does not mean “never”; rather, it means “not always.”

| Transform | Linear | Affine | Invertible | Angles preserved | Orthogonal | Rigid body | Lengths preserved | Areas/volumes preserved | Determinant |

| Lineartransformations | Y | Y | |||||||

| Affinetransformations | Y | ||||||||

| Invertibletransformations | Y | ||||||||

| Angle-preserving transformations | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Orthogonaltransformations | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Rigid bodytransformations | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 1 | |

| Translation | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 1 | |

| Rotation1 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 1 |

| Uniform scale2 | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Non-uniformscale | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Orthographicprojection4 | Y | Y | 0 | ||||||

| Reflection5 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y6 | Y | |||

| Shearing | Y | Y | Y | Y7 | 1 |

| 1 | About the origin in 2D or an axis passing through the origin in 3D. |

| 2 | About the origin in 2D or an axis passing through the origin in 3D. |

| 3 | The determinant is the square of the scale factor in 2D, and the cube of the scale factor in 3D. |

| 4 | Onto a line (2D) or plane (3D) that passes through the origin. |

| 5 | About a line (2D) or plane (3D) that passes through the origin. |

| 6 | Not considering “negative” area or volume. |

| 7 | Surprisingly! |

Exercises

-

Does the matrix below express a linear transformation? Affine?

-

Construct a matrix to rotate

-

Construct a matrix to rotate

-

Construct a matrix to rotate

- Construct a matrix that doubles the height, width, and length of an object in 3D.

-

Construct a matrix to scale by a factor of 5 about the plane

through the origin perpendicular to the vector

-

Construct a matrix to orthographically project onto the plane

through the origin perpendicular to the vector

-

Construct a matrix to reflect orthographically about the plane

through the origin perpendicular to the vector

-

An object initially had its axes and origin coincident with the

world axes and origin. It was then rotated

- (a)What is the matrix that can be used to transform row vectors from object space to world space?

- (b)What about the matrix to transform vectors from world space to object space?

- (c)Express the object's

Boy, you turn me

Inside out

And round and round