never goes back to its original dimensions.

Chapter 4 presented a few of the most of the important properties and operations of matrices and discussed how matrices can be used to express geometric transformations in general. Chapter 5 considered matrices and geometric transforms in detail. This chapter completes our coverage of matrices by discussing a few more interesting and useful matrixoperations.

- Section 6.1 covers the determinant of a matrix.

- Section 6.2 covers the inverse of a matrix.

- Section 6.3 discusses orthogonal matrices.

-

Section 6.4 introduces

homogeneous vectors and

-

Section 6.5 discusses

perspective projection and shows how to do it

with a

6.1Determinant of a Matrix

For square matrices, there is a special scalar called the determinant of the matrix. The determinant has many useful properties in linear algebra, and it also has interesting geometric interpretations.

As is our custom, we first discuss some math, and then make some geometric interpretations.

Section 6.1.1 introduces the notation for determinants and gives the linear

algebra rules for computing the determinant of a

6.1.1

Determinants of

and

matrices

The determinant of a square matrix

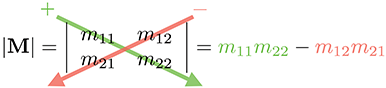

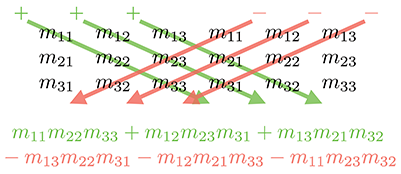

The determinant of a

Notice that when we write the determinant of a matrix, we replace the brackets with vertical lines.

Equation (6.1) can be remembered easier with the following diagram. Simply multiply entries along the diagonal and back-diagonal, then subtract the back-diagonal term from the diagonal term.

Some examples help to clarify the simple calculation:

The determinant of a

A similar diagram can be used to memorize Equation (6.2). We

write two copies of the matrix

For example,

If we interpret the rows of a

6.1.2Minors and Cofactors

Before we can look at determinants in the general case, we need to introduce some other constructs: minors and cofactors.

Assume

The cofactor of a square matrix

As shown in Equation (6.4), we use the notation

In the next section, we use minors and cofactors to compute determinants of an arbitrary

dimension

6.1.3Determinants of Arbitrary

Matrices

Several equivalent definitions exist for the determinant of a matrix of arbitrary dimension

As it turns out, it doesn't matter which row or column we choose; they all will produce the same result.

Let's look at an example. We'll rewrite the equation for

Now, let's derive the

Expanding the cofactors, we have

Determinant of a

As you can imagine, the complexity of explicit formulas for determinants of higher degree grows

rapidly. Luckily, we can perform an operation known as

“pivoting,” which doesn't affect the value

of the determinant, but causes a particular row or column to be filled with zeroes except for a

single element (the “pivot” element). Then only one cofactor has to be evaluated. Since we

won't need determinants of matrices higher than the

Let's briefly state some important characteristics concerning determinants.

-

The determinant of an identity matrix of any dimension is 1:

Determinant of identity matrix

-

The determinant of a matrix product is equal to the

product of the determinants:

Determinant of matrix product

This extends to more than two matrices:

-

The determinant of the transpose of a matrix is equal to the original

determinant:

Determinant of matrix transpose

-

If any row or column in a matrix contains all 0s, then the determinant

of that matrix is 0:

Determinant of matrix with a row/column full of 0s

-

Exchanging any pair of rows negates the determinant:

Swapping rows negates the determinant

This same rule applies for exchanging a pair of columns.

-

Adding any multiple of a row (column) to another row (column) does not change the

value of the determinant!

Adding one row to

another doesn't

change the

determinant

This explains why our shear matrices from Section 5.5 have a determinant of 1.

6.1.4Geometric Interpretation of Determinant

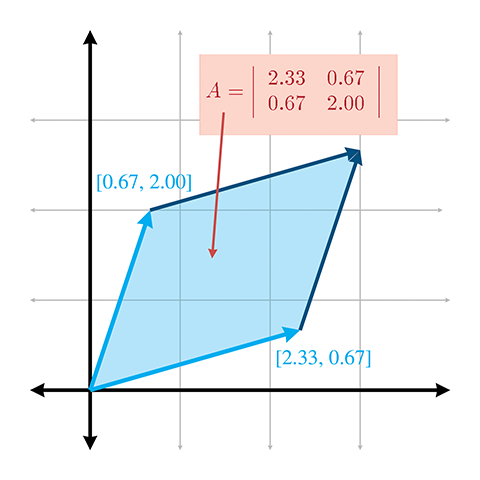

The determinant of a matrix has an interesting geometric interpretation. In 2D, the determinant is equal to the signed area of the parallelogram or skew box that has the basis vectors as two sides (see Figure 6.1). (We discussed how we can use skew boxes to visualize coordinate space transformations in Section 4.2.) By signed area, we mean that the area is negative if the skew box is “flipped” relative to its original orientation.

In 3D, the determinant is the volume of the parallelepiped that has the transformed basis vectors as three edges. It will be negative if the object is reflected (“turned inside out”) as a result of the transformation.

The determinant is related to the change in size that results from transforming by the matrix. The absolute value of the determinant is related to the change in area (in 2D) or volume (in 3D) that will occur as a result of transforming an object by the matrix, and the sign of the determinant indicates whether any reflection or projection is contained in the matrix.

The determinant of the matrix can also be used to help classify the type of transformation represented by a matrix. If the determinant of a matrix is zero, then the matrix contains a projection. If the determinant of a matrix is negative, then reflection is contained in the matrix. See Section 5.7 for more about different classes of transformations.

6.2Inverse of a Matrix

Another important operation that applies only to square matrices is the inverse of a matrix. This section discusses the matrix inverse from a mathematical and geometric perspective.

The inverse of a square matrix

Not all matrices have an inverse. An obvious example is a matrix with a row or column filled

with 0s—no matter what you multiply this matrix by, the corresponding row or column in the result will also be full of 0s.

If a matrix has an inverse, it is said to be invertible or nonsingular. A matrix

that does not have an inverse is said to be noninvertible or singular. For any

invertible matrix

The determinant of a singular matrix is zero and the determinant of a nonsingular matrix is nonzero. Checking the magnitude of the determinant is the most commonly used test for invertibility because it's the easiest and quickest. In ordinary circumstances, this is OK, but please note that the method can break down. An example is an extreme shear matrix with basis vectors that form a very long, thin parallelepiped with unit volume. This ill conditioned matrix is nearly singular, even though its determinant is 1. The condition number is the proper tool for detecting such cases, but this is an advanced topic slightly beyond the scope of this book.

There are several ways to compute the inverse of a matrix. The one we use is based on the classical adjoint, which is the subject of the next section.

6.2.1The Classical Adjoint

Our method for computing the inverse of a matrix is based on the classical adjoint. The

classical adjoint of a matrix

Let's look at an example. Take the

First, we compute the cofactors of

The classical adjoint of

6.2.2Matrix Inverse—Official Linear Algebra Rules

To compute the inverse of a matrix, we divide the classical adjoint by the determinant:

Computing matrix inverse from classical adjoint and determinantIf the determinant is zero, the division is undefined, which jives with our earlier statement that matrices with a zero determinant are noninvertible.

Let's look at an example. In the previous section we calculated the classical adjoint of a

matrix

Here the value of

There are other techniques that can be used to compute the inverse of a matrix, such as

Gaussian elimination. Many linear algebra textbooks assert that such techniques are better

suited for implementation on a computer because they require fewer arithmetic operations, and

this assertion is true for larger matrices and matrices with a structure that may be exploited.

However, for arbitrary matrices of smaller order, such as the

We close this section with a quick list of several important properties concerning matrix inverses.

-

The inverse of the inverse of a matrix is the original matrix:

(Of course, this assumes that

-

The identity matrix is its own inverse:

Note that there are other matrices that are their own inverse. For example, consider any reflection matrix, or a matrix that rotates

-

The inverse of the transpose of a matrix is the transpose of

the inverse of the matrix:

-

The inverse of a matrix product is equal to the product of the inverses of the matrices,

taken in reverse order:

This extends to more than two matrices:

-

The determinant of the inverse is the reciprocal of the determinant of the original matrix:

6.2.3Matrix Inverse—Geometric Interpretation

The inverse of a matrix is useful geometrically because it allows us to compute the “reverse”

or “opposite” of a transformation—a transformation that “undoes” another transformation if

they are performed in sequence. So, if we take a vector, transform it by a matrix

6.3Orthogonal Matrices

Previously we made reference to a special class of square matrices known as orthogonal matrices. This section investigates orthogonal matrices a bit more closely. As usual, we first introduce some pure math (Section 6.3.1), and then give some geometric interpretations (Section 6.3.2). Finally, we discuss how to adjust an arbitrary matrix to make it orthogonal (Section 6.3.3).

6.3.1Orthogonal Matrices—Official Linear Algebra Rules

A square matrix

Recall from Section 6.2.2 that, by definition, a matrix times its inverse is the

identity matrix (

This is extremely powerful information, because the inverse of a matrix is often needed, and orthogonal matrices arise frequently in practice in 3D graphics. For example, as mentioned in Section 5.7.5, rotation and reflection matrices are orthogonal. If we know that our matrix is orthogonal, we can essentially avoid computing the inverse, which is a relatively costly computation.

6.3.2Orthogonal Matrices—Geometric Interpretation

Orthogonal matrices are interesting to us primarily because their inverse is trivial to compute. But how do we know if a matrix is orthogonal in order to exploit its structure?

In many cases, we may have information about the way the matrix was constructed and therefore know a priori that the matrix contains only rotation and/or reflection. This is a very common situation, and it's very important to take advantage of this when using matrices to describe rotation. We return to this topic in Section 8.2.1.

But what if we don't know anything in advance about the matrix? In other words, how can we tell

if an arbitrary matrix

Let

This gives us nine equations, all of which must be true for

Let the vectors

Now we can rewrite the nine equations more compactly:

Conditions satisfied by an orthogonal matrixThis notational changes makes it easier for us to make some interpretations.

-

First, the dot product of a vector with itself is 1 if

and only if the vector is a unit vector. Therefore, the equations

with a 1 on the right-hand side of the equals sign

(Equations (6.8),

(6.9),

and (6.10))

will be true only when

-

Second, recall from Section 2.11.2

that the dot product of two vectors is 0 if and only if they are

perpendicular. Therefore, the other six equations (with 0 on the

right-hand side of the equals sign) are true when

So, for a matrix to be orthogonal, the following must be true:

- Each row of the matrix must be a unit vector.

- The rows of the matrix must be mutually perpendicular.

Similar statements can be made regarding the columns of the matrix, since if

Notice that these criteria are precisely those that we said in Section 3.3.3 were satisfied by an orthonormal set of basis vectors. In that section, we also noted that an orthonormal basis was particularly useful because we could perform, by using the dot product, the “opposite” coordinate transform from the one that is always available. When we say that the transpose of an orthogonal matrix is equal to its inverse, we are just restating this fact in the formal language of linear algebra.

Also notice that three of the orthogonality equations are duplicates, because the dot product is

commutative. Thus, these nine equations actually express only six constraints. In an arbitrary

When computing a matrix inverse, we will usually only take advantage of orthogonality if we know a priori that a matrix is orthogonal. If we don't know in advance, it's probably a waste of time to check. In the best case, we check for orthogonality and find that the matrix is indeed orthogonal, and then we transpose the matrix. But this may take almost as much time as doing the inversion. In the worst case, the matrix is not orthogonal, and any time we spent checking was definitely wasted. Finally, even matrices that are orthogonal in the abstract may not be exactly orthogonal when represented in floating point, and so we must use tolerances, which have to be tuned.

6.3.3Orthogonalizing a Matrix

It is sometimes the case that we encounter a matrix that is slightly out of orthogonality. We may have acquired bad data from an external source, or we may have accumulated floating point error (which is called matrix creep). For basis vectors used for bump mapping (see Section 10.9), we will often adjust the basis to be orthogonal, even if the texture mapping gradients aren't quite perpendicular. In these situations, we would like to orthogonalize the matrix, resulting in a matrix that has mutually perpendicular unit vector axes and is (hopefully) as close to the original matrix as possible.

The standard algorithm for constructing a set of orthogonal basis vectors (which is what the rows of an orthogonal matrix are) is Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization. The basic idea is to go through the basis vectors in order. For each basis vector, we subtract off the portion of that vector that is parallel to the proceeding basis vectors, which must result in a perpendicular vector.

Let's look at the

After applying these steps, the vectors

The Gram-Schmidt algorithm is biased, depending on the order in which the basis vectors are

listed. For instance,

One iteration of this algorithm results in a set of basis vectors

that are slightly “more orthogonal” than the original vectors, but

possibly not completely orthogonal. By repeating this procedure

multiple times, we can eventually converge on an orthogonal basis.

Selecting an appropriately small value for

6.4

Homogeneous Matrices

Up until now, we have used only 2D and 3D vectors. In this

section, we introduce 4D vectors and the so-called “homogeneous” coordinate. There is nothing

magical about 4D vectors and matrices (and no, the fourth coordinate in this case isn't

“time”). As we will see, 4D vectors and

This section introduces 4D homogeneous space and

6.4.14D Homogeneous Space

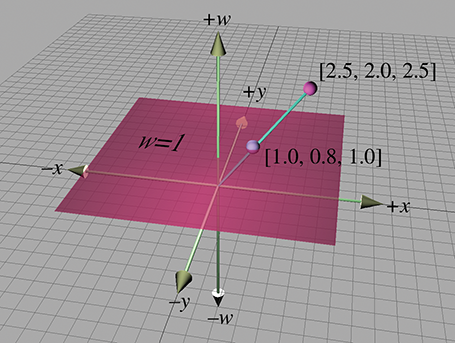

As was mentioned in Section 2.1, 4D vectors have four components, with

the first three components being the standard

To understand how the standard physical 3D space is extended into 4D, let's first examine

homogeneous coordinates in 2D, which are of the form

For any given physical 2D point

When

The same basic idea applies when extending physical 3D space to 4D homogeneous space (although

it's a lot harder to visualize). The physical 3D points can be thought of as living in the

hyperplane in 4D at

Homogeneous coordinates and projection by division by

6.4.2

Translation Matrices

Recall from Section 4.2 that a

Assume for the moment that

When we multiply a 4D vector of the form

Now for the interesting part. In 4D, we can also express translation as a matrix multiplication, something we were not able to do in 3D:

Using aIt is important to understand that this matrix multiplication is still a linear transformation. Matrix multiplication cannot represent “translation” in 4D, and the 4D zero vector will always be transformed back into the 4D zero vector. The reason this trick works to transform points in 3D is that we are actually shearing 4D space. (Compare Equation (6.11) with the shear matrices from Section 5.5.) The 4D hyperplane that corresponds to physical 3D space does not pass through the origin in 4D. Thus, when we shear 4D space, we are able to translate in 3D.

Let's examine what happens when we perform a transformation without translation followed by a

transformation with only translation. Let

Then we could rotate and then translate a point

Remember that the order of transformations is important, and since we have chosen to use row vectors, the order of transformations coincides with the order that the matrices are multiplied, from left to right. We are rotating first and then translating.

Just as with

Let's now examine the contents of

Notice that the upper

Applying this information in reverse, we can take any

Let's see what happens with the so-called “points at infinity” (those vectors with

In other words, when we transform a point-at-infinity vector of the form

When we transform a point-at-infinity vector by a transformation that does contain translation, we get the following result:

Multiplying a “point at infinity” by aNotice that the result is the same—that is, no translation occurs.

In other words, the

So, one reason why

-

We cannot multiply a

-

We cannot invert a

-

When we multiply a 4D vector by a

Strict adherence to linear algebra rules forces us to add the fourth column. Of course, in our

code, we are not bound by linear algebra rules. It is a common technique to write a

6.4.3General Affine Transformations

Chapter 5 presented

- rotation about an axis that does not pass through the origin,

- scale about a plane that does not pass through the origin,

- reflection about a plane that does not pass through the origin, and

- orthographic projection onto a plane that does not pass through the origin.

The basic idea is to translate the “center” of the transformation to the origin, perform the

linear transformation by using the techniques developed in Chapter 5, and

then transform the center back to its original location. We start with a translation matrix

It is interesting to observe the general form of such a matrix. Let's first write

Evaluating the matrix multiplication, we get

Thus, the extra translation in an affine transformation changes only the last row of the

Our use of “homogeneous” coordinates so far has really been nothing more than a mathematical

kludge to allow us to include translation in our transformations. We use quotations around

“homogeneous” because the

6.5

Matrices and Perspective Projection

Section 6.4.1 showed that when we interpret

a 4D homogeneous vector in 3D, we divide by

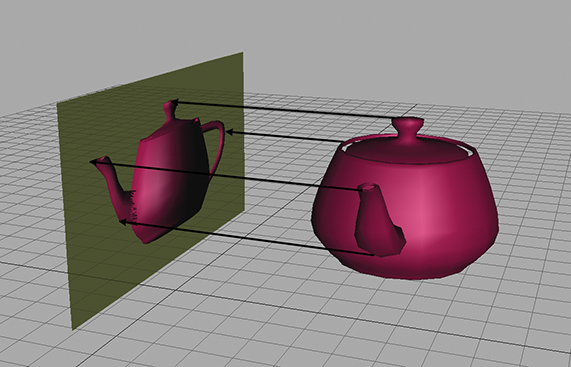

We can learn a lot about perspective projection by comparing it to another type of projection we have already discussed, orthographic projection. Section 5.3 showed how to project 3D space onto a 2D plane, known as the projection plane, by using orthographic projection. Orthographic projection is also known as parallel projection, because the projectors are parallel. (A projector is a line from the original point to the resulting projected point on the plane). The parallel projectors used in orthographic projection are shown in Figure 6.3.

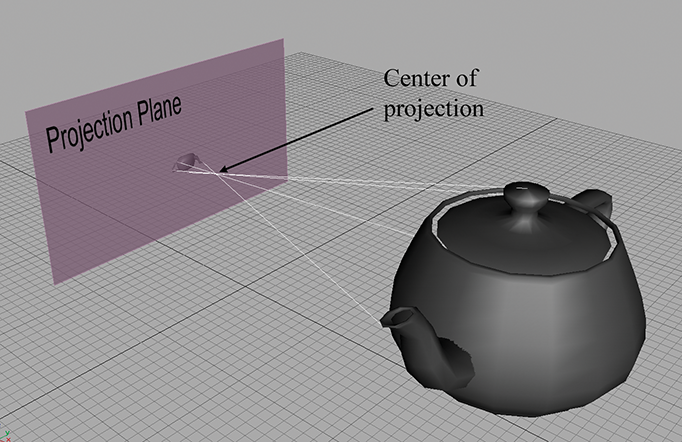

Perspective projection in 3D also projects onto a 2D plane. However, the projectors are not parallel. In fact, they intersect at a point, known as the center of projection. This is shown in Figure 6.4.

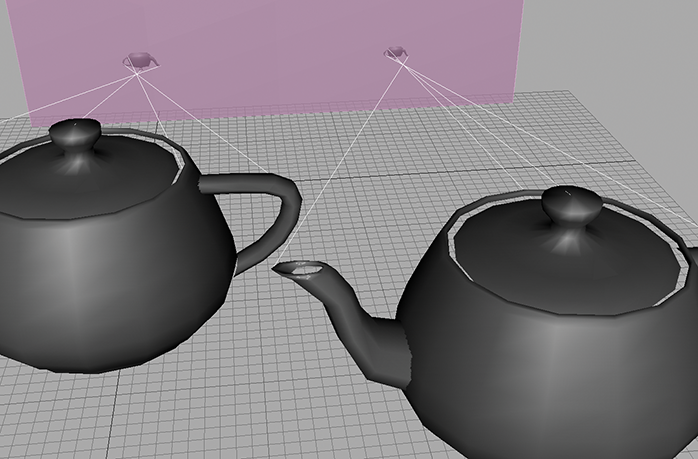

Because the center of projection is in front of the projection plane, the projectors cross before striking the plane, and thus the image is inverted. As we move an object farther away from the center of projection, its orthographic projection remains constant, but the perspective projection gets smaller, as illustrated in Figure 6.5. The teapot on the right is further from the projection plane, and the projection is (slightly) smaller than the closer teapot. This is a very important visual cue known as perspective foreshortening.

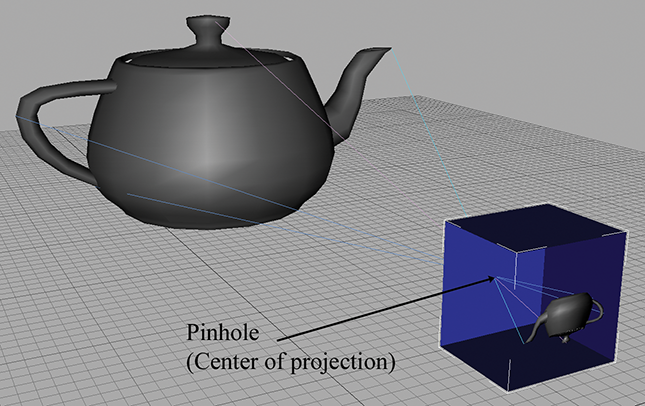

6.5.1A Pinhole Camera

Perspective projection is important in graphics because it models the way the human visual system works. Actually, the human visual system is more complicated because we have two eyes, and for each eye, the projection surface (our retina) is not flat; so let's look at the simpler example of a pinhole camera. A pinhole camera is a box with a tiny hole on one end. Rays of light enter the pinhole (thus converging at a point), and then strike the opposite end of the box, which is the projection plane. This is shown in Figure 6.6.

In this view, the left and back sides of the box have been removed so you can see the inside. Notice that the image projected onto the back of the box is inverted. This is because the rays of light (the projectors) cross as they meet at the pinhole (the center of projection).

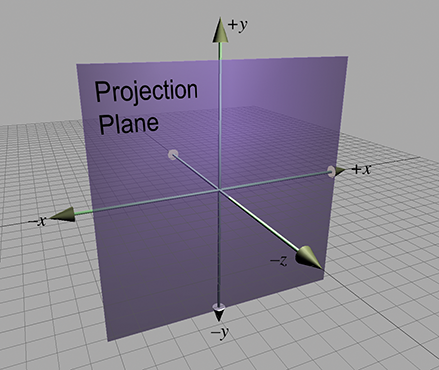

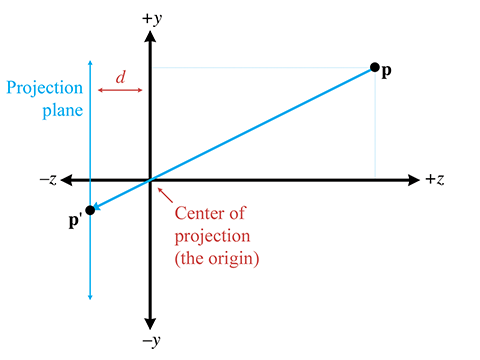

Let's examine the geometry behind the perspective projection of a pinhole camera. Consider a 3D

coordinate space with the origin at the pinhole, the

Let's see if we can't compute, for an arbitrary point

By similar triangles, we can see that

Notice that since a pinhole camera flips the image upside down, the signs of

The

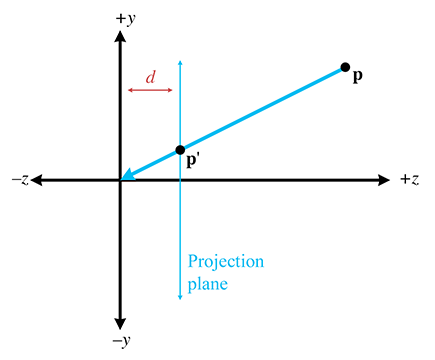

In practice, the extra minus signs create unnecessary complexities, and so we move the plane of

projection to

As expected, moving the plane of projection in front of the center of projection removes the annoying minus signs:

Projecting a point onto the plane6.5.2Perspective Projection Matrices

Because the conversion from 4D to 3D space implies a division, we can encode a perspective

projection in a

First, we manipulate Equation (6.12) to have a common denominator:

To divide by this denominator, we put the denominator into

So we need a

Thus, we have derived a

There are several important points to be made here:

-

Multiplication by this matrix doesn't actually perform the perspective

transform, it just computes the proper denominator into

-

There are many variations. For example, we can place the plane of

projection at

-

This seems overly complicated. It seems like it would be simpler to

just divide by

-

The projection matrix in a real graphics geometry pipeline

(perhaps more accurately known as the “clip matrix”) does more than

just copy

-

Most graphics systems apply a normalizing scale factor

such that

-

The projection matrix in most graphics systems

also scales the

-

Most graphics systems apply a normalizing scale factor

such that

Exercises

-

Compute the determinant of the following matrix:

-

Compute the determinant, adjoint, and inverse of the

following matrix:

-

Is the following matrix orthogonal?

- Invert the matrix from the previous exercise.

-

Invert the

-

Construct a

-

Construct a

-

Construct a

-

Construct a

-

Use the matrix from the previous exercise to compute the 3D

coordinates of the projection of the point

Take a point, stretch it into a line, curl it into a circle,

twist it into a sphere, and punch through the sphere.

-

The notation “