The Cartesian coordinate system isn't the only system for mapping out space and defining locations precisely. An alternative to the Cartesian system is the polar coordinate system, which is the subject of this chapter. If you're not very familiar with polar coordinates, it might seem like an esoteric or advanced topic (especially because of the trig), and you might be tempted to gloss over. Please don't make this mistake. There are many very practical problems in areas such as AI and camera control whose solutions (and inherent difficulties!) can be readily understood in the framework of polar coordinates.

This chapter is organized into the following sections:

- Section 7.1 describes 2D polar coordinates.

- Section 7.2 gives some examples where polar coordinates are preferable to Cartesian coordinates.

- Section 7.3 shows how polar space works in 3D and introduces cylindrical and spherical coordinates.

- Finally, Section 7.4 makes it clear that polar space can be used to describe vectors as well as positions.

7.12D Polar Space

This section introduces the basic idea behind polar coordinates, using two dimensions to get us warmed up. Section 7.1.1 shows how to use polar coordinates to describe position. Section 7.1.2 discusses aliasing of polar coordinates. Section 7.1.3 shows how to convert between polar and Cartesian coordinates in 2D.

7.1.1Locating Points by Using 2D Polar Coordinates

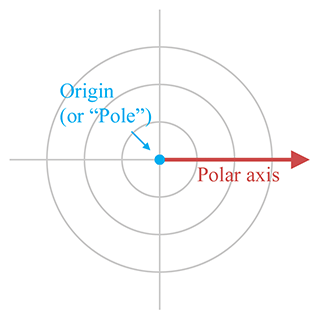

Remember that a 2D Cartesian coordinate space has an origin, which establishes the position of

the coordinate space, and two axes that pass through the origin, which establish the orientation

of the space. A 2D polar coordinate space also has an origin (known as the pole), which

has the same basic purpose—it defines the “center” of the coordinate space. A polar

coordinate space has only one axis, however, sometimes called the polar axis, which

is usually depicted as a ray from the origin. It is customary in math literature for the polar

axis to point to the right in diagrams, and thus it corresponds to the

In the Cartesian coordinate system, we described a 2D point using two signed distances,

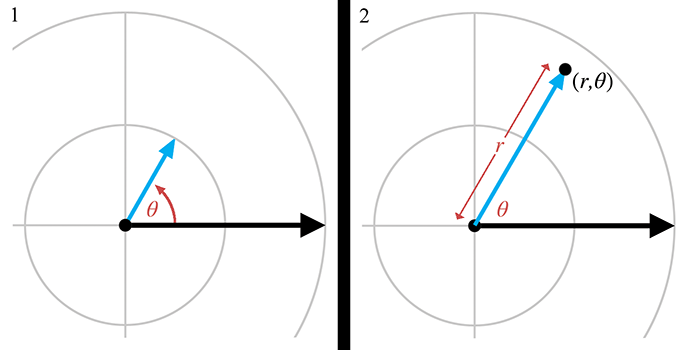

Step 1.Start at the origin, facing in the direction of the polar

axis, and rotate by the angle

Step 2.Now move forward from the origin a distance of

This process is shown in Figure 7.2.

In summary,

You might have noticed that the diagrams of polar coordinate spaces contain grid lines, but that

these grid lines are slightly different from the grid lines used in diagrams of Cartesian

coordinate systems. Each grid line in a Cartesian coordinate system is composed of points with

the same value for one of the coordinates. A vertical line is composed of points that all have

the same

-

The “grid circles” show lines of constant

-

The straight grid lines that pass through the origin show

lines of constant

One note regarding angle measurements. With Cartesian coordinates, the unit of measure wasn't really significant. We could interpret diagrams using feet, meters, miles, yards, light-years, beard-seconds, or picas, and it didn't really matter.1 If you take some Cartesian coordinate data, interpreting that data using different physical units just makes whatever you're looking at get bigger or smaller, but it's proportionally the same shape. However, interpreting the angular component of polar coordinates using different angular units can produce drastically distorted results.

It really doesn't matter whether you use degrees or radians (or grads, mils, minutes, signs,

sextants, or Furmans), as long as you keep it straight. In the text of this book, we almost

always give specific angular measurements in degrees and use the

7.1.2Aliasing

Hopefully you're starting to get a good feel for how polar coordinates work and what polar coordinate space looks like. But there may be some nagging thoughts in the back of your head. Consciously or subconsciously, you may have noticed a fundamental difference between Cartesian and polar space. Perhaps you imagined a 2D Cartesian space as a perfectly even continuum of space, like a flawless sheet of Jell-O, spanning infinitely in all directions, each infinitely thin bite identical to all the others. Sure, there are some “special” places, like the origin, and the axes, but those are just like marks on the bottom of the pan—the Jell-O itself is the same there as everywhere else. But when you imagined the fabric of polar coordinate space, something was different. Polar coordinate space has some “seams” in it, some discontinuities where things are a bit “patched together.” In the infinitely large circular pan of Jell-O, there are multiple sheets of Jell-O stacked on top of each other. When you put your spoon down a particular place to get a bite, you often end up with multiple bites! There's a piece of hair in the block of Jell-O, a singularity that requires special precautions.

Whether your mental image of polar space was of Jell-O, or some other yummy dessert, you were probably pondering some of these questions:

-

Can the radial distance

-

Can

-

The value of the angle

-

The polar coordinates for the origin itself are also ambiguous. Clearly

The answer to all of these questions is “yes.”3 In fact, we must face a rather harsh reality about polar space.

This phenomenon is known as aliasing. Two coordinate pairs are said to be aliases

of each other if they have different numeric values but refer to the same point in space. Notice

that aliasing doesn't happen in Cartesian space—each point in space is assigned exactly one

Before we discuss some of the difficulties created by aliasing,

let's be clear about one task for which aliasing does not

pose any problems: interpreting a particular polar coordinate pair

When

One way to create an alias for a point

In general, for any point

where

So, in spite of aliasing, we can all agree what point is described by the polar coordinates

It's like reducing fractions. We all agree that

For polar coordinates, the “preferred” way to describe any given point is known as the

canonical coordinates for that point. A 2D polar coordinate pair

The following algorithm can be used to convert a polar coordinate pair into its canonical form:

Converting a polar coordinate pair-

If

-

If

-

If

-

If

Listing 7.1 shows how it could be done in C. As discussed in Section 7.1.1, our computer code will normally store angles using radians.

// Radial distance

float r;

// Angle in RADIANS

float theta;

// Declare a constant for 2*pi (360 degrees)

const float TWOPI = 2.0f*PI;

// Check if we are exactly at the origin

if (r == 0.0f) {

// At the origin - slam theta to zero

theta = 0.0f;

} else {

// Handle negative distance

if (r < 0.0f) {

r = -r;

theta += PI;

}

// Theta out of range? Note that this if() check is not

// strictly necessary, but we try to avoid doing floating

// point operations if they aren't necessary. Why

// incur floating point precision loss if we don't

// need to?

if (fabs(theta) > PI) {

// Offset by PI

theta += PI;

// Wrap in range 0...TWOPI

theta -= floor(theta / TWOPI) * TWOPI;

// Undo offset, shifting angle back in range -PI...PI

theta -= PI;

}

}

Picky readers may notice that while this code ensures that

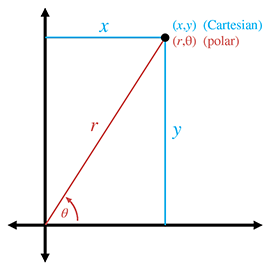

7.1.3Converting between Cartesian and

Polar Coordinates in 2D

This section describes how to convert between the Cartesian and polar coordinate systems in 2D. By the way, if you were wondering when we were going to make use of the trigonometry that we reviewed in Section 1.4.5, this is it.

Figure 7.4 shows the geometry involved in converting between polar and Cartesian coordinates in 2D.

Converting polar coordinates

Notice that aliasing is a nonissue; Equation (7.1) works even for

“weird” values of

Computing the polar coordinates

We can easily compute

Since the square root function always returns the positive root, we

don't have to worry about

Computing

Unfortunately, there are two problems with this approach. The first is that if

Because of these problems, the complete equation for conversion from Cartesian to polar coordinates

requires some “if statements” to handle each quadrant, and is a bit of a mess for “math

people.” Luckily, “computer people” have the atan2 function, which properly

computes the angle

Let's make two key observations about Equation (7.2). First, following the convention of the

atan2 function found in the standard libraries of most computer languages, the

arguments are in the “reverse” order:

Second, in many software libraries, the atan2 function is undefined at the

origin, when

Back to the task at hand: computing the polar angle

The C code in Listing 7.2 shows how to convert a Cartesian

// Input: Cartesian coordinates

float x,y;

// Output: polar radial distance, and angle in RADIANS

float r, theta;

// Check if we are at the origin

if (x == 0.0f && y == 0.0f) {

// At the origin - slam both polar coordinates to zero

r = 0.0f;

theta = 0.0f;

} else {

// Compute values. Isn't the atan2 function great?

r = sqrt(x*x + y*y);

theta = atan2(y,x);

}

7.2Why Would Anybody Use Polar Coordinates?

With all of the complications with aliasing, degrees and radians, and trig, why would anybody use polar coordinates when Cartesian coordinates work just fine, without any hairs in the Jell-O? Actually, you probably use polar coordinates more often than you do Cartesian coordinates. They arise frequently in informal conversation.

For example, one author is from Alvarado, Texas. When people ask where Alvarado, Texas, is, he tells them, “About 15 miles southeast of Burleson.” He's describing where Alvarado is by using polar coordinates, specifying an origin (Burleson), a distance (15 miles), and an angle (southeast). Of course, most people who aren't from Texas (and many people who are) don't know where Burleson is, either, so it's more natural to switch to a different polar coordinate system and say, “About 50 miles southwest of Dallas.” Luckily, even people from outside the United States usually know where Dallas is.6 By the way, everyone in Texas does not wear a cowboy hat and boots. We do use the words “y'all” and “fixin',” however.7

In short, polar coordinates often arise because people naturally think about locations in terms of distance and direction. (Of course, we often aren't very precise when using polar coordinates, but precision is not really one of the brain's strong suits.) Cartesian coordinates are just not our native language. The opposite is true of computers—in general, when using a computer to solve geometric problems, it's easier to use Cartesian coordinates than polar coordinates. We discuss this difference between humans and computers again in Chapter 8 when we compare different methods for describing orientation in 3D.

Perhaps the reason for our affinity for polar coordinates is that each polar coordinate has

concrete meaning all by itself. One fighter pilot may say to another “Bogey, six

o'clock!”8 In the midst of a dogfight, these brave fighter pilots

are actually using polar coordinates. “Six o'clock” means “behind you” and is basically the

angle

In video games, one of the most common times that polar coordinates arise is when we want to aim a camera, weapon, or something else at some target. This problem is easily handled by using a Cartesian-to-polar coordinate conversion, since it's usually the angles we need. Even when angular data can be avoided for such purposes (we might be able to completely use vector operations, for example, if the orientation of the object is specified using a matrix), polar coordinates are still useful. Usually, cameras and turrets and assassins' arms cannot move instantaneously (no matter how good the assassin), but targets do move. In this situation, we usually “chase” the target in some manner. This chasing (whatever type of control system is used, whether a simple velocity limiter, a lag, or a second-order system) is usually best done in polar space, rather than, say, interpolating a target position in 3D space.

Polar coordinates are also often encountered with physical data acquisition systems that provide basic raw measurements in terms of distance and direction.

One final occasion worth mentioning when polar coordinates are more natural to use than Cartesian coordinates is moving around on the surface of a sphere. When would anybody do that? You're probably doing it right now. The latitude/longitude coordinates used to precisely describe geographic locations are really not Cartesian coordinates, they are polar coordinates. (To be more precise, they are a type of 3D polar coordinates known as spherical coordinates, which we'll discuss in Section 7.3.2.) Of course, if you are looking at a relatively small area compared to the size of the planet and you're not too far away from the equator, you can use latitude and longitude as Cartesian coordinates without too many problems. We do it all the time in Dallas.

7.33D Polar Space

Polar coordinates can be used in 3D as well as 2D. As you probably have already guessed, 3D

polar coordinates have three values. But is the third coordinate another linear distance

(like

Section 7.3.1 discusses one kind of 3D polar coordinates, cylindrical coordinates, and Section 7.3.2 discusses the other kind of 3D polar coordinates, spherical coordinates. Section 7.3.3 presents some alternative polar coordinate conventions that are often more streamlined for use in video game code. Section 7.3.4 describes the special types of aliasing that can occur in spherical coordinate space. Section 7.3.5 shows how to convert between spherical coordinates and 3D Cartesian coordinates.

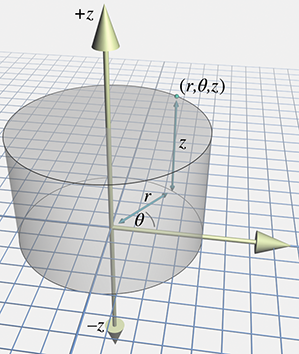

7.3.1Cylindrical Coordinates

To extend Cartesian coordinates into 3D, we start with the 2D system, used for working in the

plane, and add a third axis perpendicular to this plane. This is basically how cylindrical

coordinates work to extend polar coordinates into 3D. Let's call the third axis the

Conversion between 3D Cartesian coordinates and cylindrical coordinates is straightforward. The

We don't use cylindrical coordinates much in this book, but they are useful in some situations

when working in a cylinder-shaped environment or describing a cylinder-shaped object. In the same

way that people often use polar coordinates without knowing it (see Section 7.2),

people who don't know the term “cylindrical coordinates” may still use them. Be aware that

even when people do acknowledge that they are using cylindrical coordinates, notation and

conventions vary widely. For example, some people use the notation

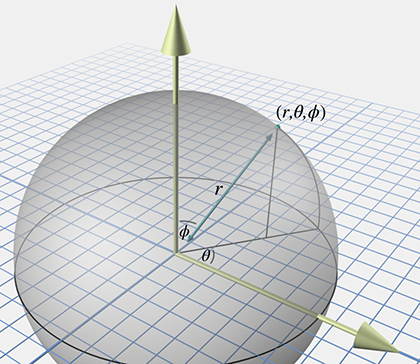

7.3.2Spherical Coordinates

The more common kind of 3D polar coordinate system is a spherical coordinate system. Whereas a set of cylindrical coordinates has two distances and one angle, a set of spherical coordinates has two angles and one distance.

Let's review the essence of how polar coordinates work in 2D. A point is specified by giving a

direction (

Different people use different conventions and notation for spherical coordinates, but most math

people have agreed that the two angles are named

Step 1.Begin by standing at the origin, facing the direction of the horizontal polar axis. The vertical axis points from your feet to your head. Point your right10 arm straight up, in the direction of the vertical polar axis.

Step 2.Rotate counterclockwise by the angle

Step 3.Rotate your arm downward by the angle

Step 4.Displace from the origin along this direction by the distance

Figure 7.6 shows how this works.

The horizontal angle

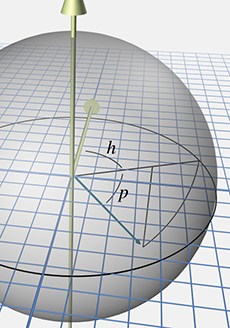

7.3.3Some Polar Conventions Useful in 3D Virtual Worlds

The spherical coordinate system described in the previous section is the traditional right-handed system used by math people, and the formulas for converting between Cartesian and spherical coordinates are rather elegant under these assumptions. However, for most people in the video game industry, this elegance is only a minor benefit to be weighed against the following irritating disadvantages of the traditional conventions:

-

The default horizontal direction at

-

The conventions for the angle

-

No offense to the Greeks, but

- It would be nice if the two angles for spherical coordinates were the same as the first two angles we use for Euler angles,12 which are used to describe orientation in 3D. We're not going to discuss Euler angles until Section 8.3, so for now let us disagree with Descartes twice-over by saying “It'd be nice because we told you so.”13

- It's a right-handed system, and we use a left-handed system (in this book at least).

Let's describe some spherical coordinate conventions that are better suited for our purposes. We

have no complaints against the standard conventions for the radial distance

The horizontal angle

The vertical angle

Figure 7.7 shows how heading and pitch conspire to define a direction.

7.3.4Aliasing of Spherical Coordinates

Section 7.1.2 examined the bothersome phenomenon of aliasing of 2D polar coordinates: different numerical coordinate pairs are aliases of each other when they refer to the same point in space. Three basic types of aliasing were presented, which we review here because they are also present in the 3D spherical coordinate system.

The first sure-fire way to generate an alias is to add a multiple of

The other two forms of aliasing are a bit more interesting because they are caused by the

interdependence of the coordinates. In other words, the meaning of one coordinate,

-

The aliasing in 2D polar space can be triggered by

negating the radial distance

-

The singularity in 2D polar space occurs at the origin, because

the angular coordinate is irrelevant when

So spherical coordinates exhibit similar aliasing behavior because the meaning of

-

Different heading and pitch values can result in the same direction, even excluding

trivial aliasing of each individual angle. An alias of (

-

A singularity occurs when the pitch angle is set to

Just as we did in 2D, we can define a set of canonical spherical coordinates such that any given

point in 3D space maps unambiguously to exactly one coordinate triple within the canonical set.

We place similar restrictions on

The following algorithm can be used to convert a spherical coordinate triple into its canonical form:

Converting a spherical coordinate triple-

If

-

If

-

If

-

If

-

If

-

If

-

If

Listing 7.3 shows how it could be done in C. Remember that computers like radians.

// Radial distance

float r;

// Angles in radians

float heading, pitch;

// Declare a few constants

const float TWOPI = 2.0f*PI; // 360 degrees

const float PIOVERTWO = PI/2.0f; // 90 degrees

// Check if we are exactly at the origin

if (r == 0.0f) {

// At the origin - slam angles to zero

heading = pitch = 0.0f;

} else {

// Handle negative distance

if (r < 0.0f) {

r = -r;

heading += PI;

pitch = -pitch;

}

// Pitch out of range?

if (fabs(pitch) > PIOVERTWO) {

// Offset by 90 degrees

pitch += PIOVERTWO;

// Wrap in range 0...TWOPI

pitch -= floor(pitch / TWOPI) * TWOPI;

// Out of range?

if (pitch > PI) {

// Flip heading

heading += PI;

// Undo offset and also set pitch = 180-pitch

pitch = 3.0f*PI/2.0f - pitch; // p = 270 degrees - p

} else {

// Undo offset, shifting pitch in range

// -90 degrees ... +90 degrees

pitch -= PIOVERTWO;

}

}

// Gimbal lock? Test using a relatively small tolerance

// here, close to the limits of single precision.

if (fabs(pitch) >= PIOVERTWO*0.9999) {

heading = 0.0f;

} else {

// Wrap heading, avoiding math when possible

// to preserve precision

if (fabs(heading) > PI) {

// Offset by PI

heading += PI;

// Wrap in range 0...TWOPI

heading -= floor(heading / TWOPI) * TWOPI;

// Undo offset, shifting angle back in range -PI...PI

heading -= PI;

}

}

}

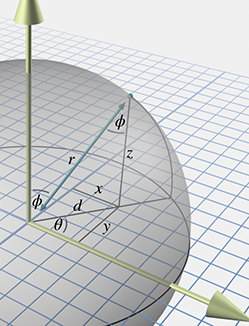

7.3.5 Converting between Spherical and Cartesian Coordinates

Let's see if we can convert spherical coordinates to 3D Cartesian coordinates. Examine Figure 7.8, which shows both spherical and Cartesian coordinates. We first develop the conversions using the traditional right-handed conventions for both Cartesian and spherical spaces, and then we show conversions applicable to our left-handed conventions.

Notice in Figure 7.8 that we've introduced a new variable

and so we're left to compute

Consider that if

Notice that when

These equations are applicable for right-handed math people. If we adopt our conventions for both the Cartesian (see Section 1.3.4) and spherical (see Section 7.3.3) spaces, the following formulas should be used:

Spherical-to-Cartesian conversion for the conventions used in this bookConverting from Cartesian coordinates to spherical coordinates is more complicated, due to aliasing. We know that there are multiple sets of spherical coordinates that map to any given 3D position; we want the canonical coordinates. The derivation that follows uses our preferred aviation-inspired conventions in Equation (7.3) because those conventions are the ones most commonly used in video games.

As with 2D polar coordinates, computing

As before, the singularity at the origin, where

The heading angle is surprisingly simple to compute using our

The trick works because

Finally, once we know

The

Listing 7.4 illustrates the entire procedure.

// Input Cartesian coordinates

float x,y,z;

// Output radial distance

float r;

// Output angles in radians

float heading, pitch;

// Declare a few constants

const float TWOPI = 2.0f*PI; // 360 degrees

const float PIOVERTWO = PI/2.0f; // 90 degrees

// Compute radial distance

r = sqrt(x*x + y*y + z*z);

// Check if we are exactly at the origin

if (r > 0.0f) {

// Compute pitch

pitch = asin(-y/r);

// Check for gimbal lock, since the library atan2

// function is undefined at the (2D) origin

if (fabs(pitch) >= PIOVERTWO*0.9999) {

heading = 0.0f;

} else {

heading = atan2(x,z);

}

} else {

// At the origin - slam angles to zero

heading = pitch = 0.0f;

}

7.4Using Polar Coordinates to Specify Vectors

We've seen how to describe a point by using polar coordinates, and how to describe a vector by using Cartesian coordinates. It's also possible to use polar form to describe vectors. Actually, to say that we can “also” use polar form is sort of like saying that a computer is controlled with a keyboard but it can “also” be controlled with the mouse. Polar coordinates directly describe the two key properties of a vector—its direction and length. In Cartesian form, these values are stored indirectly and obtained only through some computations that essentially boil down to a conversion to polar form. This is why, as we discussed in Section 7.2, polar coordinates are the local currency in everyday conversation.

But it isn't just laymen who prefer polar form. It's interesting to notice that most physics textbooks contain a brief introduction to vectors, and this introduction is carried out using a framework of polar coordinates. This is done despite the fact that it makes the math significantly more complicated.

As for the details of how polar vectors work, we've actually already covered them. Consider our “algorithm”FIXME link for locating a point described by 2D polar coordinates. If you take out the phrase “start at the origin” and leave the rest intact, the instructions describe how to visualize the displacement (vector) described by any given polar coordinates. This is the same idea from Section 2.4: a vector is related to the point with the same coordinates because it gives us the displacement from the origin to that point.

We've also already learned the math for converting vectors between Cartesian and polar form. The methods discussed in Section 7.1.3 were presented in terms of points, but they are equally valid for vectors.

Exercises

-

Plot and label the points with the following polar coordinates:

-

Convert the following 2D polar coordinates to canonical

form:

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (a)

-

Convert the following 2D polar coordinates to Cartesian

form:

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (e)

- (a)

- Convert the polar coordinates in Exercise 2 to Cartesian form.

-

Convert the following 2D Cartesian coordinates to (canonical) polar form:

- (a)

- (b)

-

(c)

- (d)

- (e)

-

(f)

- (a)

-

Convert the following cylindrical coordinates to Cartesian form:

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (a)

-

Convert the following 3D Cartesian coordinates to (canonical) cylindrical form:

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (a)

-

Convert the following spherical coordinates

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (a)

-

Interpret the spherical coordinates (a)–(d) from the previous exercise as

- 1.Convert to canonical

- 2.Use the canonical coordinates to convert to Cartesian form (using the video game conventions).

- 1.Convert to canonical

-

Convert the following 3D Cartesian coordinates to (canonical) spherical form using our

modified convention:

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (e)

- (f)

- (a)

-

What do the “grid lines” look like in spherical space? Assuming the spherical

conventions used in this book, describe the shape defined by the set of all points that

meet the following criteria. Do not restrict the coordinates to the canonical set.

- (a)A fixed radius

- (b)A fixed heading

- (c)A fixed pitch

- (a)A fixed radius

- During crunch time one evening, a game developer decided to get some fresh air and go for a walk. The developer left the studio walking south and walked for 5 km. She then turned east and walked another 5 km. Realizing that all the fresh air was making her light-headed, she decided to return to the studio. She turned north, walked 5 km and was back at the studio, ready to squash the few remaining programming bugs left on her list. Unfortunately, waiting for her at the door was a hungry bear, and she was eaten alive.14 What color was the bear?

I did not make use of intelligence, mathematics or maps.

- There might be some employees at NASA who feel otherwise, since the $125 million Mars Climate Orbiter went astray due to a bug involving confusion between metric and English units. Perhaps we should say that knowing the specific units of measurement isn't necessary to understand the concepts of Cartesian coordinates.

- Such as math professors.

- Even question 3.

-

Warning: extremely large values of

-

Speaking of math teachers and reduced fractions, one author remembers his middle

school math teacher engaged in a fierce debate about whether a mixed fraction such as

- This is due to Dallas's two rather unfortunate claims to fame: the assassination of President Kennedy and a soap opera named after the city, which inexplicably had international appeal.

- These two facts have nothing to do with math, but everything to do with correcting misconceptions.

- The authors have never actually heard anything like this first-hand. However, they have seen it in movies.

-

- We mean no prejudice against our left-handed readers; you may imagine using your left arm if you wish. However, this is a right-handed coordinate system, so you may feel more official using your imaginary right arm. Save your left arm for later, when we discuss some left-handed conventions.

- Earth's radius is about 6,371 km (3,959 miles), on average.

- It's been said that the name Euler is a one-word math test: if you know how to pronounce it, then you've learned some math. Please make the authors of this book proud by passing this test, and pronouncing it “oiler,” not “yooler.”

- You read the first part of Chapter 1, right?

- We know this scenario is totally impossible. I mean, a game developer taking a walk during crunch time?!