you may end up where you are heading.

This chapter tackles the difficult problem of describing the orientation of an object in 3D. It also discusses the closely related concepts of rotation and angular displacement. There are several different ways we can express orientation and angular displacement in 3D. Here we discuss the three most important methods—matrices, Euler angles, and quaternions—as well as two lesser known forms—axis-angle and exponential map. For each method, we define precisely how the representation method works, and discuss the peculiarities, advantages, and disadvantages of the method.

Different techniques are needed in different circumstances, and each technique has its advantages and disadvantages. It is important to know not only how each method works, but also which technique is most appropriate for a particular situation and how to convert between representations.

The discussion of orientation in 3D is divided into the following sections:

- Section 8.1 discusses the subtle differences between terms like “orientation,” “direction,” and “angular displacement.”

- Section 8.2 describes how to express orientation using a matrix.

- Section 8.3 describes how to express angular displacement using Euler angles.

- Section 8.4 describes the axis-angle and exponential map forms.

- Section 8.5 describes how to express angular displacement using a quaternion.

- Section 8.6 compares and contrasts the different methods.

- Section 8.7 explains how to convert an orientation from one form to another.

8.1What Exactly is “Orientation”?

Before we can begin to discuss how to describe orientation in 3D, let us first define exactly what it is that we are attempting to describe. The term orientation is related to other similar terms, such as

- direction

- angular displacement

- rotation.

Intuitively, we know that the “orientation” of an object basically tells us what direction the object is facing. However, “orientation” is not exactly the same as “direction.”

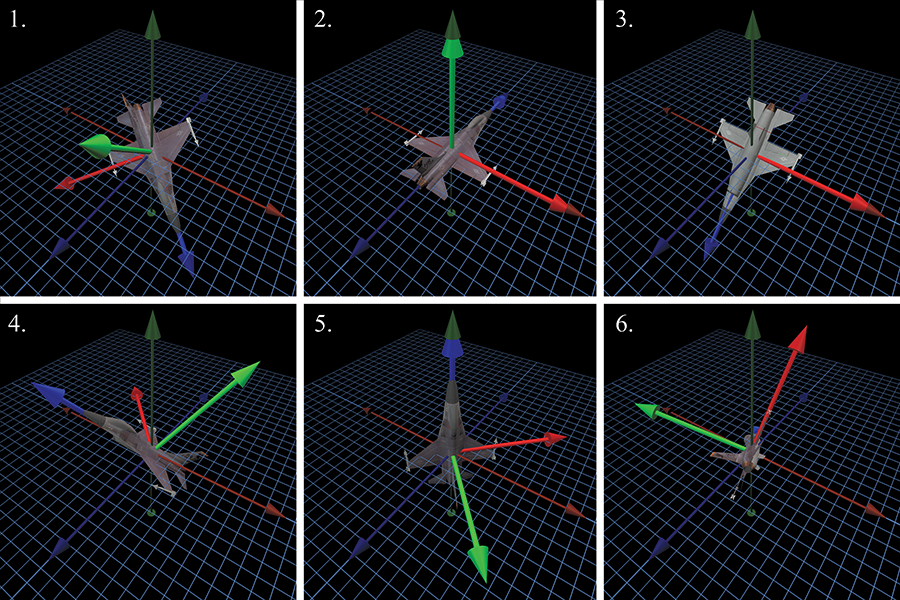

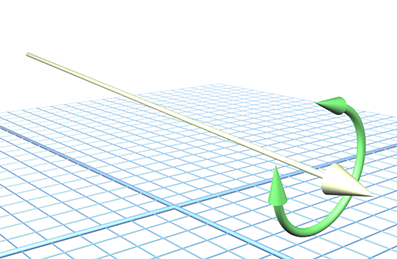

For example, a vector has a direction, but not an orientation. The difference is that when a vector points in a certain direction, you can twist the vector along its length (see Figure 8.1), and there is no real change to the vector, since a vector has no thickness or dimension other than its length.

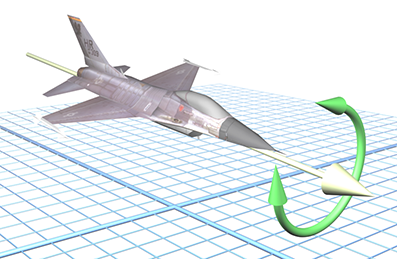

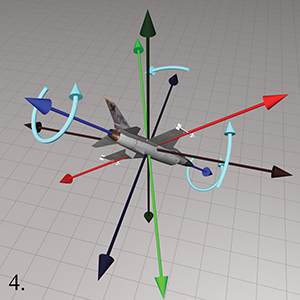

In contrast to a simple vector, consider an object, such as a jet, facing a certain direction. If we twist the jet (see Figure 8.2) in the same way that we twisted the vector, we will change the orientation of the jet. In Section 8.3, we refer to this twisting component of an object's orientation as bank.

The fundamental difference between direction and orientation is seen concretely by the fact that we can parameterize a direction in 3D with just two numbers (the spherical coordinate angles—see Section 7.3.2), whereas an orientation requires a minimum of three numbers (Euler angles—see Section 8.3).

Section 2.4.1 discussed that it's impossible to describe the position of an object in absolute terms—we must always do so within the context of a specific reference frame. When we investigated the relationship between “points” and “vectors,” we noticed that specifying a position is actually the same as specifying an amount of translation from some other given reference point (usually the origin of some coordinate system).

In the same way, orientation cannot be described in absolute terms. Just as a position is given by a translation from some known point, an orientation is given by a rotation from some known reference orientation (often called the “identity” or “home” orientation). The amount of rotation is known as an angular displacement. In other words, describing an orientation is mathematically equivalent to describing an angular displacement.

We say “mathematically equivalent” because in this book, we make a subtle distinction between

“orientation” and terms such as “angular displacement” and “rotation.” It is helpful to

think of an “angular displacement” as an operator that accepts an input and produces an output.

A particular direction of transformation is implied; for example, the angular displacement

from the old orientation to the new orientation, or from upright space

to object space. An example of an angular displacement is, “Rotate

However, we frequently encounter state variables and other situations in which this operator framework of input/output is not helpful and a parent/child relationship is more natural. We tend to use the word “orientation” in those situations. An example of an orientation is, “Standing upright and facing east.” It describes a state of affairs.

Of course, we can describe the orientation “standing upright and facing east” as an angular

displacement by saying, “Stand upright, facing north, and then rotate

You might also hear the word “attitude” used to refer the orientation of an object, especially if that object is an aircraft.

8.2Matrix Form

One way to describe the orientation of a coordinate space in 3D is to tell which way the basis

vectors of that coordinate space (the

When these basis vectors are used to form the rows of a

8.2.1Which Matrix?

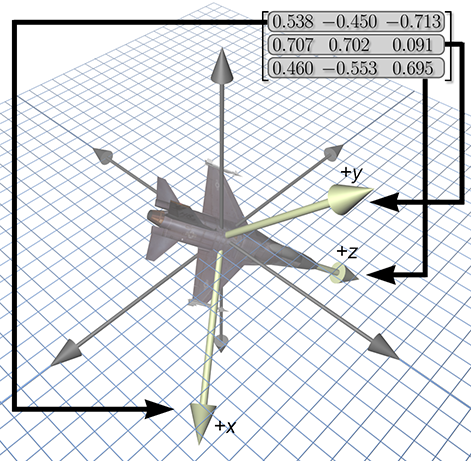

We have already seen how a matrix can be used to transform points from one coordinate space to another. In Figure 8.3, the matrix in the upper right-hand corner can be used to rotate points from the object space of the jet into upright space. We've pulled out the rows of this matrix to emphasize their direct relationship to the coordinates for the jet's body axes. The rotation matrix contains the object axes, expressed in upright space. Simultaneously, it is a rotation matrix: we can multiply row vectors by this matrix to transform those vectors from object-space coordinates to upright-space coordinates.

Legitimate question to ask are: Why does the matrix contain the body axes expressed using upright-space coordinates? Why not the upright axes expressed in object-space coordinates? Another way to phrase this is, Why did we choose to give a rotation matrix that transforms vectors from object space to upright space? Why not from upright space to object space?

From a mathematical perspective, this question is a bit ridiculous. Because rotation matrices are orthogonal, their inverse is the same as their transpose (see Section 6.3.2). Thus, the decision is entirely a cosmetic one.

But practically speaking, in our opinion, it is quite important. At issue is whether you can write code that is intuitive to read and works the first time, or whether it requires a lot of work to decipher, or a knowledge of conventions that are not stated because they are “obvious” to everyone but you. So please allow us a brief digression to continue a line of thought begun when we introduced the term “upright space” in Section 3.2.4 concerning the practical aspects of what happens when the math of coordinate space transformations gets translated into code. Also please allow some latitude to express some opinions based on our observations watching programmers grapple with rotation matrices. We don't expect that everyone will agree with our assertions, but we hope that every reader will at least appreciate the value in considering these issues.

Certainly every good math library will have a

It is common practice to use the generic transform matrix class to describe the orientation of an object. In this case, rotation is treated just like any other transformation. The interface remains in terms of a source and destination space. Unfortunately, it is our experience that the following two matrix operations are by far the most commonly used:2

- Take an object-space vector and express it in upright coordinates.

- Take an upright-space vector and express it in object coordinates.

Notice that we need to be able to go in both directions. We have no experience or evidence that either direction is significantly more common than the other. But more important, the very nature of the operations and the way programmers think about the operations is in terms of “object space” and “upright space” (or some other equivalent terminology, such as “parent space” and “child space”). We do not think of them in terms of a source space and a destination space. It is in this context that we wish to consider the question posed at the beginning of this section: Which matrix should we use?

First, we should back up a bit and remind ourselves of the mathematically moot but yet

conceptually important distinction between orientation and angular displacement. (See the notes

on terminology at the end of Section 8.1.) If your purpose is to create a matrix

that performs a specific angular displacement (for example, “rotate 30 degrees about the

Let's assume that we adopt the common policy and store orientation using the generic transformation matrix. We are forced to arbitrarily pick a convention, so let's decide that multiplication by this matrix will transform from object to upright space. If we have a vector in upright space and we need to express it in object-space coordinates, we must multiply this vector by the inverse3 of the matrix.

Now let's see how our policy affects the code that is written and read hundreds of times by average game programmers.

- Rotate some vector from object space to upright space is translated into code as multiplication by the matrix.

- Rotate a vector from upright space to object space is translated into code as multiplication by the inverse (or transpose) of the matrix.

Notice that the code does not match one-to-one with the high-level intentions of the programmer. It forces every user to remember what the conventions are every time they use the matrix. It is our experience that this coding style is a contributing factor to the difficulty that beginning programmers have in learning how to use matrices; they often end up transposing and negating things randomly when things don't look right.

We have found it helpful to have a special

So, back to the question posed at the start of this section: Which matrix should we use? Our answer is, “It shouldn't matter.” By that we mean there is a way to design your matrix code in such a way that it can be used without knowing what choice was made. As far as the C++ code goes, this is purely a cosmetic change. For example, perhaps we just replace the function name multiply() with objectToUpright(), and likewise we replace multiplyByTranspose() with uprightToObject(). The version of the code with descriptive, named coordinate spaces is easier to read and write.

8.2.2Direction Cosines Matrix

You might come across the (very old school) term direction cosines in the context of using

a matrix to describe orientation. A direction cosines matrix is the same thing as a rotation

matrix; the term just refers to a special way to interpret (or construct) the matrix, and this

interpretation is interesting and educational, so let's pause for a moment to take a closer look.

Each element in a rotation matrix is equal to the dot product of a cardinal axis in one space

with a cardinal axis in the other space. For example, the center element

More generally, let's say that the basis vectors of a coordinate space are the mutually

orthogonal unit vectors

These axes can be interpreted as geometric rather than numeric entities, so it really does not matter what coordinates are used to describe the axes (provided we use the same coordinate space to describe all of them), the rotation matrix will be the same.

For example, let's say that our axes are described using coordinates relative to the first basis.

Then

In other words, the rows of the rotation matrix are the basis vectors of the output coordinate space, expressed by using the coordinates of the input coordinate space. Of course, this fact is not just true for rotation matrices, it's true for all transformation matrices. This is the central idea of why a transformation matrix works, which was developed in Section 4.2.

Now let's look at the other case. Instead of using coordinates relative to the first basis,

we'll measure everything using the second coordinate space (the output space). This time,

This says that the columns of the rotation matrix are formed from the basis vectors of the input space, expressed using the coordinates of the output space. This is not true of transformation matrices in general; it applies only to orthogonal matrices such as rotation matrices.

Also, remember that our convention is to use row vectors on the left. If you are using column vectors on the right, things will be transposed.

8.2.3Advantages of Matrix Form

Matrix form is a very explicit form of representing orientation. This explicit nature provides some benefits.

- Rotation of vectors is immediately available. The most important property of matrix form is that you can use a matrix to rotate vectors between object and upright space. No other representation of orientation allows this4—to rotate vectors, we must convert the orientation to matrix form.

- Format used by graphics APIs. Partly due to reasons in the previous item, graphics APIs use matrices to express orientation. (API stands for Application Programming Interface. Basically, this is the code we use to communicate with the graphics hardware.) When we are communicating with the API, we are going to have to express our transformations as matrices. How we store transformations internally in our program is up to us, but if we choose another representation, we are going to have to convert them into matrices at some point in the graphics pipeline.

- Concatenation of multiple angular displacements. A third advantage of matrices is that it is possible to “collapse” nested coordinate space relationships. For example, if we know the orientation of object A relative to object B, and we know the orientation of object B relative to object C, then by using matrices, we can determine the orientation of object A relative to object C. We encountered these concepts before when we discussed nested coordinate spaces in Chapter 3, and then we discussed how matrices could be concatenated in Section 5.6.

- Matrix inversion. When an angular displacement is represented in matrix form, it is possible to compute the “opposite” angular displacement by using matrix inversion. What's more, since rotation matrices are orthogonal, this computation is a trivial matter of transposing the matrix.

8.2.4Disadvantages of Matrix Form

The explicit nature of a matrix provides some advantages, as we have just discussed. However, a matrix uses nine numbers to store an orientation, and it is possible to parameterize orientation with only three numbers. The “extra” numbers in a matrix can cause some problems.

- Matrices take more memory. If we need to store many orientations (for example, keyframes in an animation sequence), that extra space for nine numbers instead of three can really add up. Let's take a modest example. Let's say we are animating a model of a human that is broken up into 15 pieces for different body parts. Animation is accomplished strictly by controlling the orientation of each part relative to its parent part. Assume we are storing one orientation for each part, per frame, and our animation data is stored at a modest rate, say, 15 Hz. This means we will have 225 orientations per second. Using matrices and 32-bit floating point numbers, each frame will take 8,100 bytes. Using Euler angles (which we will meet next in Section 8.3), the same data would take only 2,700 bytes. For a mere 30 seconds of animation data, matrices would take 162K more than the same data stored using Euler angles!

-

Difficult for humans to use. Matrices are not intuitive for humans to work

with directly. There are just too many numbers, and they are all between

- Matrices can be ill-formed. As we have said, a matrix uses nine numbers, when only three are necessary. In other words, a matrix contains six degrees of redundancy. There are six constraints that must be satisfied for a matrix to be “valid” for representing an orientation. The rows must be unit vectors, and they must be mutually perpendicular (see Section 6.3.2).

Let's consider this last point in more detail. If we take any nine numbers at random and create a

How could we ever end up with a bad matrix? There are several ways:

- We may have a matrix that contains scale, skew, reflection, or projection. What is the “orientation” of an object that has been affected by such operations? There really isn't a clear definition for this. Any nonorthogonal matrix is not a well-defined rotation matrix. (See Section 6.3 for a complete discussion on orthogonal matrices.) And reflection matrices (which are orthogonal) are not valid rotation matrices, either.

- We may just get bad data from an external source. For example, if we are using a physical data acquisition system, such as motion capture, there could be errors due to the capturing process. Many modeling packages are notorious for producing ill-formed matrices.

- We can actually create bad data due to floating point round off error. For example, suppose we apply a large number of incremental changes to an orientation, which could routinely happen in a game or simulation that allows a human to interactively control the orientation of an object. The large number of matrix multiplications, which are subject to limited floating point precision, can result in an ill-formed matrix. This phenomenon is known as matrix creep. We can combat matrix creep by orthogonalizing the matrix, as we already discussed in Section 6.3.3.

8.2.5Summary of Matrix Form

Let's summarize what Section 8.2 has said about matrices.

- Matrices are a “brute force” method of expressing orientation: we explicitly list the basis vectors of one space in the coordinates of some different space.

- The term direction cosines matrix alludes to the fact that each element in a rotation matrix is equal to the dot product of one input basis vector with one output basis vector. Like all transformation matrices, the rows of the matrix are the output-space coordinates of the input-space basis vectors. Furthermore, the columns of a rotation matrix are the input-space coordinates of the output-space basis vectors, a fact that is only true by virtue of the orthogonality of a rotation matrix.

- The matrix form of representing orientation is useful primarily because it allows us to rotate vectors between coordinate spaces.

- Modern graphics APIs express orientation by using matrices.

- We can use matrix multiplication to collapse matrices for nested coordinate spaces into a single matrix.

- Matrix inversion provides a mechanism for determining the “opposite” angular displacement.

- Matrices can take two to three times as much memory as other techniques. This can become significant when storing large numbers of orientations, such as animation data.

- The numbers in a matrix aren't intuitive for humans to work with.

- Not all matrices are valid for describing an orientation. Some matrices contain mirroring or skew. We can end up with a ill-formed matrix either by getting bad data from an external source or through matrix creep.

8.3Euler Angles

Another common method of representing orientation is known as Euler angles. (Remember, Euler is pronounced “oiler,” not “yoolur.”) The technique is named after the famous mathematician who developed them, Leonhard Euler (1707–1783). Section 8.3.1 describes how Euler angles work and discusses the most common conventions used for Euler angles. Section 8.3.2 discusses other conventions for Euler angles, including the important fixed axis system. We consider the advantages and disadvantages of Euler angles in Section 8.3.3 and Section 8.3.4. Section 8.3.5 summarizes the most important concepts concerning of Euler angles.

8.3.1What Are Euler Angles?

The basic idea behind Euler angles is to define an angular displacement as a sequence of three rotations about three mutually perpendicular axes. This sounds complicated, but actually it is quite intuitive. (In fact, its ease of use by humans is one of its primary advantages.)

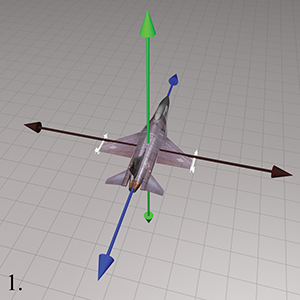

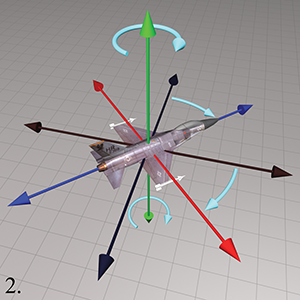

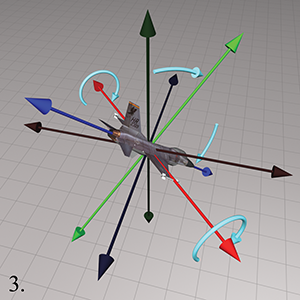

So Euler angles describe orientation as three rotations about three mutually perpendicular axes. But which axes? And in what order? As it turns out, any three axes in any order will work, but most people have found it practical to use the cardinal axes in a particular order. The most common convention, and the one we use in this book, is the so-called “heading-pitch-bank” convention for Euler angles. In this system, an orientation is defined by a heading angle, a pitch angle, and a bank angle.

Before we define the terms heading, pitch, and bank precisely, let us briefly review the

coordinate space conventions we use in this book. We use a left-handed system, where

Given heading, pitch, and bank angles, we can determine the orientation described by these Euler angles using a simple four-step process.

Step 1.Begin in the “identity” orientation—that is, with the

object-space axes aligned with the upright axes.

Step 2.Perform the heading rotation, rotating about the

Step 3.After heading has been applied, pitch measures the amount of

rotation about the

Step 4.After heading and pitch angles have been applied, bank

measures the amount of rotation about the

It may seem contradictory that positive bank is counterclockwise, since positive heading is clockwise. But notice that positive heading is clockwise when viewed from the positive end of the axis towards the origin, the opposite perspective from the one used when judging clockwise/counterclockwise for bank. If we look from the origin to the positive end of the

Now you have reached the orientation described by the Euler angles. Notice the similarity of Steps 1–3 to the procedure used in Section 7.3.2 to locate the direction described by the spherical coordinate angles. In other words, we can think of heading and pitch as defining the basic direction that the object is facing, and bank defining the amount of twist.

8.3.2Other Euler Angle Conventions

The heading-pitch-bank system described in the previous section isn't the only way to define a rotation using three angles about mutually perpendicular axes. There are many variations on this theme. Some of these differences turn out to be purely nomenclature; others are more meaningful. Even if you like our conventions, we encourage you to not skip this section, as some very important concepts are discussed; these topics are the source of much confusion, which we hope to dispel.

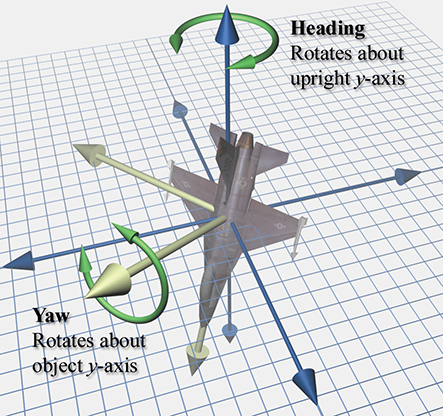

First of all, there is the trivial issue of naming. The most common variation you will find was made popular by the field of aerospace, the yaw-pitch-roll method.5 The term “roll” is completely synonymous with bank, and for all purposes they are identical. Similarly, within the limited context of yaw-pitch-roll, the term “yaw” is practically identical to the term heading. (However, in a broader sense, the word “yaw” actually has a subtly different meaning, and it is this subtle difference that drives our preference for the term heading. We discuss this rather nit-picky distinction in just a moment, but for the moment yaw and heading are the same.) So essentially yaw-pitch-roll is the same system as heading-pitch-bank.

Other less common terms are often used. Heading also goes by the name azimuth. The vertical angle that we call pitch is also called attitude or elevation. The final angle of rotation, which we call “bank,” is sometimes called tilt or twist.

And, of course, there are those perverse mathematicians who (motivated by the need to save space when writing on a chalkboard?) insist on assaulting your eyeballs with a slew of Greek letters. You may see any of the following:

It's all Greek to usOf course, these are cosmetic differences. Perhaps more interesting is that fact that you will often hear these same three words listed in the opposite order: roll-pitch-yaw. (A quick Google search for “roll pitch yaw” or “yaw pitch roll” yields plenty of results for both forms, with neither appearing more predominant.) Considering how the order of rotations is so critical, are people really that perverse that they choose to list them in the reverse order? We're not just dwelling on terminology here; the distinctions in thinking hinted at by the differences in terminology will actually become useful when we consider how to convert Euler angles to a rotation matrix. As it turns out, there is a perfectly reasonable explanation for this “backwards” convention: it's the order in which we actually do the rotations inside a computer!

The fixed-axis system is very closely related to the Euler angle system. In an Euler angle system, the rotation occurs about the body axes, which change after each rotation. Thus, for example, the physical axis for the bank angle is always the longitudinal body space axis, but in general it is arbitrarily oriented in upright space. In a fixed-axis system, in contrast, the axes of rotation are always the fixed, upright axes. But as it turns out, the fixed-axis system and the Euler angle system are actually equivalent, provided that we take the rotations in the opposite order.

You should visualize the following example to

convince yourself this is true. Let's say we have a heading (yaw) of

Now we'd like to make a brief but humble campaign for a more precise use of the term “yaw.” A lot

of aeronautical terminology is inherited nautical terminology.6 In a nautical context, the original meaning of the word “yaw” was

essentially the same thing as heading, both in terms of absolute angle and also a change in that

angle. In the context of airplanes and other freely rotating bodies, however, we don't feel that

yaw and heading are the same thing. A yawing motion produces a rotation about the object

In contrast, when players navigating a first-person shooter move the mouse from left to right,

they are performing a heading rotation. The rotation is always about the vertical axis

(the upright

Alas, the same argument can be leveled against the term “pitch.” If bank is nonzero, an incremental change to the middle Euler angle does not produce a rotation about the object's lateral axis. But then, there isn't really a simple, good word to describe the angle that the object's longitudinal axis makes with the horizontal, which is what the middle Euler angle really specifies. (“Inclination” is no good as it is specific to the right-handed conventions.)

We hope you have read our opinions with the humility we intended, and also have received the more important message: investigating (seemingly cosmetic) differences in convention can sometimes lead us to a deeper understanding of the finer points. And then sometimes it's just plain nit-picking. Generations of aerospace engineers have been putting men on the moon and robots on Mars, and building airplanes that safely shuttle the authors to and from distant cities, all the while using the terms yaw and roll. Would you believe that some of these guys don't even know who we are!? Given the choice to pick your own terminology, we say to use the word “heading” when you can, but if you hear the word “yaw,” then for goodness sake don't make as big of a deal out of it as we have in these pages, especially if the person you are talking to is smarter than you.

Although in this book we do not follow the right-handed aerospace coordinate conventions (and we have a minor quibble about terminology), when it comes to the basic strategy of Euler angles, in a physical sense, we believe complete compliance with the wisdom of the aerospace forefathers is the only way to go, at least if your universe has some notion of “ground.” Remember that, in theory, any three axes can be used as the axes of rotation, in any order. But really, the conventions they chose are the only ones that make any practical sense, if you want the individual angles to be useful and meaningful. No matter how you label your axes, the first angle needs to rotate about the vertical, the second about the body lateral axis, and the third about the body longitudinal axis.

As if these weren't enough complications, let us throw in a few more. In the system we have been describing, each rotation occurs about a different body axes. However, Euler's own original system was a “symmetric” system in which the first and last rotations are performed around the same axis. These methods are more convenient in certain situations, such as describing the motion of a top, where the three angles correspond to precession, nutation, and spin. You may encounter some purists who object to the name “Euler angles” being attached to an asymmetric system, but this usage is widespread in many fields, so rest assured that you outnumber them. To distinguish between the two systems, the symmetric Euler angles are sometimes called “proper” Euler angles, with the more common conventions being called Tait-Bryan angles, first documented by the aerospace forefathers we mentioned [1]. O'Reilly [10] discusses proper Euler angles, even more methods of describing rotation, such as the Rodrigues vector, Cayley-Klein parameters, and interesting historical remarks. James Diebel's summary [3] compares different Euler angle conventions and the other major methods for describing rotation, much as this chapter does, but assumes a higher level of mathematical sophistication.

If you have to deal with Euler angles that use a different convention from the one you prefer, we offer two pieces of advice:

- First, make sure you understand exactly how the other Euler angle system works. Little details such as the definition of positive rotation and order of rotations make a big difference.

- Second, the easiest way to convert the Euler angles to your format is to convert them to matrix form and then convert the matrix back to your style of Euler angles. We will learn how to perform these conversions in Section 8.7. Fiddling with the angles directly is much more difficult than it would seem. See [12] for more information.

8.3.3Advantages of Euler Angles

Euler angles parameterize orientation using only three numbers, and these numbers are angles. These two characteristics of Euler angles provide certain advantages over other forms of representing orientation.

- Euler angles are easy for humans to use—considerably easier than matrices or quaternions. Perhaps this is because the numbers in an Euler angle triple are angles, which is naturally how people think about orientation. If the conventions most appropriate for the situation are chosen, then the most practical angles can be expressed directly. For example, the angle of declination is expressed directly by the heading-pitch-bank system. This ease of use is a serious advantage. When an orientation needs to be displayed numerically or entered at the keyboard, Euler angles are really the only choice.

-

Euler angles use the smallest possible representation. Euler angles use

three numbers to describe an orientation. No system can parameterize 3D orientation

using fewer than three numbers. If memory is at a premium, then Euler angles are the

most economical way to represent an orientation.

Another reason to choose Euler angles when you need to save space is that the numbers you are storing are more easily compressed. It's relatively easy to pack Euler angles into a smaller number of bits using a trivial fixed-precision system. Because Euler angles are angles, the data loss due to quantization is spread evenly. Matrices and quaternions require using very small numbers, because the values stored are sines and cosines of the angles. The absolute numeric difference between two values is not proportionate to the perceived difference, however, as it is with Euler angles. In general, matrices and quaternions don't pack into a fixed-point system easily.

Bottom line: if you need to store a lot of 3D rotational data in as little memory as possible, as is very common when handling animation data, Euler angles (or the exponential map format—to be discussed in Section 8.4) are the best choices. - Any set of three numbers is valid. If we take any three numbers at random, they form a valid set of Euler angles that we can interpret as an expression of an orientation. In other words, there is no such thing as an invalid set of Euler angles. Of course, the numbers may not be correct but at least they are valid. This is not the case with matrices and quaternions.

8.3.4Disadvantages of Euler Angles

This section discusses some disadvantages of the Euler angle method of representing orientation; primarily,

- The representation for a given orientation is not unique.

- Interpolating between two orientations is problematic.

Let's address these points in detail. First, we have the problem that for a given orientation, there are many different Euler angle triples that can be used to describe that orientation. This is known as aliasing and can be somewhat of an inconvenience. These irritating problems are very similar to those we met dealing with spherical coordinates in Section 7.3.4. Basic questions such as “Do two Euler angle triples represent the same angular displacement?” are difficult to answer due to aliasing.

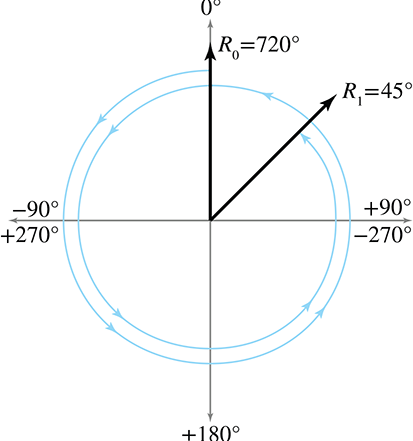

We've seen one trivial type of aliasing before with polar coordinates: adding a multiple of

A second and more troublesome form of aliasing occurs because the three angles are not completely independent of each other. For example, pitching down 135° is the same as heading 180°, pitching down 45°, and then banking 180°.

To deal with aliasing of spherical coordinates, we found it useful to establish a canonical

set; any given point has a unique representation in the canonical set that is the “official” way

to describe that point using polar coordinates. We use a similar technique for Euler angles. In

order to guarantee a unique Euler angle representation for any given orientation, we restrict the

ranges of the angles. One common technique is to limit heading and bank to

The most famous (and irritating) type of aliasing problem suffered by Euler angles is illustrated

by this example: if we head right

This last rule for Gimbal lock completes the rules for the canonical set of Euler angles:

Conditions satisfied by Euler angles in the canonical setWhen writing C++ that accepts Euler angle arguments, it's usually best to ensure that they work given Euler angles in any range. Luckily this is usually easy; things frequently just work without taking any extra precaution, especially if the angles are fed into trig functions. However, when writing code that computes or returns Euler angles, it's good practice to return the canonical Euler angle triple. The conversion methods shown in Section 8.7 demonstrate these principles.

So for purposes of simply describing orientation, aliasing isn't a huge problem, especially

when canonical Euler angles are used. So what's so bad about aliasing and Gimbal lock? Let's say we

wish to interpolate between two orientations

The naïve approach to this problem is to apply the standard linear interpolation formula (“lerp”) to each of the three angles independently:

Simple linear interpolation between two anglesThis is fraught with problems.

First, if canonical Euler angles are not used, we may have large

angle values. For example, imagine the heading of

Of course, the solution to this problem is to use canonical Euler angles. We could assume that

we will always be interpolating between two sets of canonical Euler angles. Or we could attempt

to enforce this by converting to canonical values inside our interpolation routine. (Simply

wrapping angles within the

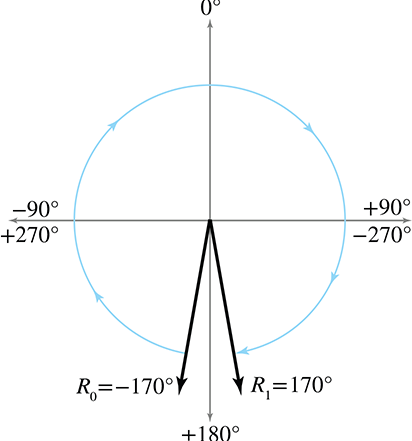

However, even using canonical angles doesn't completely solve the problem. A second type of

interpolation problem can occur because of the cyclic nature of rotation angles. Suppose

The solution to this second type of problem is to wrap the differences between angles used in the

interpolation equation in the range

where

The

float wrapPi(float theta) {

// Check if already in range. This is not strictly necessary,

// but it will be a very common situation. We don't want to

// incur a speed hit and perhaps floating precision loss if

// it's not necessary

if (fabs(theta) <= PI) {

// One revolution is 2 PI.

const float TWOPPI = 2.0f*PI;

// Out of range. Determine how many "revolutions"

// we need to add.

float revolutions = floor((theta + PI) * (1.0f/TWOPPI));

// Subtract it off

theta -= revolutions*TWOPPI;

}

return theta;

}

Let's go back to Euler angles. As expected, using

But even with these two Band-Aids, Euler angle interpolation still suffers from Gimbal lock, which in many situations causes a jerky, unnatural course. The object whips around suddenly and appears to be hung somewhere. The basic problem is that the angular velocity is not constant during the interpolation. If you have never experienced what Gimbal lock looks like, you may be wondering what all the fuss is about. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to fully appreciate the problem from illustrations in a book—you need to experience it in real time. Fortunately, though, it's easy to find an animation demonstrating the problem: just do a youtube.com search for “gimbal lock.”

The first two problems with Euler angle interpolation were irritating, but certainly not

insurmountable. Canonical Euler angles and

8.3.5Summary of Euler Angles

Let's summarize our findings from Section 8.3 about Euler angles.

- Euler angles store orientation by using three angles. These angles are ordered rotations about the three object-space axes.

- The most common system of Euler angles is the heading-pitch-bank system. Heading and pitch tell which way the object is facing—heading gives a “compass reading” and pitch measures the angle of declination. Bank measures the amount of “twist.”

- In a fixed-axis system, the rotations occur about the upright axes rather than the moving body axes. This system is equivalent to Euler angles, provided that we perform the rotations in the opposite order.

- Lots of smart people use lots of different terms for Euler angles, and they can have good reasons for using different conventions.7 It's best not to rely on terminology when using Euler angles. Always make sure you get a precise working definition, or you're likely to get very confused.

- In most situations, Euler angles are more intuitive for humans to work with compared to other methods of representing orientation.

- When memory is at a premium, Euler angles use the minimum amount of data possible for storing an orientation in 3D, and Euler angles are more easily compressed than quaternions.

- There is no such thing as an invalid set of Euler angles. Any three numbers have a meaningful interpretation.

- Euler angles suffer from aliasing problems due to the cyclic nature of rotation angles and because the rotations are not completely independent of one another.

-

Using canonical Euler angles can simplify many basic queries on Euler angles. An

Euler angle triple is in the canonical set if heading and bank are in the range

-

Gimbal lock occurs when pitch is

- Contrary to popular myth, any orientation in 3D can be represented by using Euler angles, and we can agree on a unique representation for that orientation within the canonical set.

-

The

- Simple forms of aliasing are irritating, but there are workarounds. Gimbal lock is a more fundamental problem with no easy solution. Gimbal lock is a problem because the parameter space of orientation has a discontinuity. This means small changes in orientation can result in large changes in the individual angles. Interpolation between orientations using Euler angles can freak out or take a wobbly path.

8.4Axis-Angle and Exponential Map

Representations

Euler's name is attached to all sorts of stuff related to rotation (we just

discussed Euler angles in Section 8.3). His name is also attached to Euler's

rotation theorem, which basically says that any 3D angular displacement can be accomplished via

a single rotation about a carefully chosen axis. To be more precise, given any two

orientations

Euler's rotation theorem leads to two closely related methods for describing orientation. Let's

begin with some notation. Assume we have chosen a rotation angle

Taking the two values

We're not going to discuss the axis-angle and exponential map forms in quite as much detail as the

other methods of representing orientation because in practice their use is a bit specialized. The

axis-angle format is primarily a conceptual tool. It's important to understand, but the method gets

relatively little direct use compared to the other formats. It's one notable capability is that we

can directly obtain an arbitrary multiple of the displacement. For example, given a rotation in

axis-angle form, we can obtain a rotation that represents one third of the rotation or 2.65 times

the rotation, simply by multiplying

The exponential map gets more use than the axis-angle. First of all, its interpolation properties are nicer than Euler angles. Although it does have singularities (discussed next), they are not as troublesome as for Euler angles. Usually, when one thinks of interpolating rotations, one immediately thinks of quaternions; however, for some applications, such as storage of animation data, the underappreciated exponential map can be a viable alternative [5]. But the most important and frequent use of the exponential map is to store not angular displacement, but rather angular velocity. This is because the exponential map differentiates nicely (which is somewhat related to its nicer interpolation properties) and can represent multiple rotations easily.

Like Euler angles, the axis-angle and exponential map forms exhibit aliasing and singularities,

although of a slightly more restricted and benign manner. There is an obvious singularity at the

identity orientation, or the quantity “no angular displacement.” In this case,

The other aliases cannot be dispatched so easily. As with Euler angles, adding a multiple of

As it turns out, given any angular displacement that can be described by a rotation matrix, the

exponential map representation is uniquely determined. Although more than one exponential map

may produce the same rotation matrix, it is possible to take a subset of the exponential maps

(those for which

Now let's consider concatenating multiple rotations. Let's say

Before we leave this topic, a regretful word of warning regarding terminology. Alternative names for these two simple concepts abound. We have tried to choose the most standard names possible, but it was difficult to find strong consensus. Some authors use the term “axis-angle” to describe both of these (closely related) methods and don't really distinguish between them. Even more confusing is the use of the term “Euler axis” to refer to either form (but not to Euler angles!). “Rotation vector” is another term you might see attached to what we are calling exponential map. Finally, the term “exponential map,” in the broader context of Lie algebra, from whence the term originates, actually refers to an operation (a “map”) rather than a quantity. We apologize for the confusion, but it's not ourfault.

8.5Quaternions

The term quaternion is somewhat of a buzzword in 3D math. Quaternions carry a certain mystique—which is a euphemismistic way of saying that many people find quaternions complicated and confusing. We think the way quaternions are presented in most texts contributes to their confusion, and we hope that our slightly different approach will help dispel quaternions' “mystique.”

There is a mathematical reason why using only three numbers to represent a 3-space orientation is guaranteed to cause the problems we discussed with Euler angles, such as Gimbal lock. It has something to do with some fairly advanced9 math terms such as “manifolds.” A quaternion avoids these problems by using four numbers to express an orientation (hence the name quaternion).

This section describes how to use a quaternion to define an angular displacement. We're going to deviate somewhat from the traditional presentation, which emphasizes the interesting (but, in our opinion, nonessential) interpretation of quaternions as complex numbers. Instead, we will be developing quaternions from a primarily geometric perspective. Here's what's in store: First, Section 8.5.1 introduces some basic notation. Section 8.5.2 is probably the most important section—it explains how a quaternion may be interpreted geometrically. Sections 8.5.3 through Section 8.5.11 review the basic quaternion properties and operations, examining each from a geometric perspective. Section 8.5.12 discusses the important slerp operation, which is used to interpolate between two quaternions and is one of the primary advantages of quaternions. Section 8.5.13 discusses the advantages and disadvantages of quaternions. Section 8.5.14 is an optional digression into how quaternions may be interpreted as 4D complex numbers. Section 8.5.15 summaries the properties of quaternions.

8.5.1Quaternion Notation

A quaternion contains a scalar component and a 3D vector component. We usually refer to the

scalar component as

In some cases it will be convenient to use the shorter notation, using

We also may write expanded quaternions vertically:

Unlike regular vectors, there is no significant distinction between “row” and “column” quaternions. We are free to make the choice strictly for aesthetic purposes.

We denote quaternion variables with the same typeface conventions used for vectors: lowercase

letters in bold (e.g.,

8.5.2What Do Those Four Numbers Mean?

The quaternion form is closely related to the axis-angle and exponential map forms from

Section 8.4. Let's briefly review the notation from that section, as

the same notation will be used here. The unit vector

A quaternion also contains an axis and angle, but

Keep in mind that

The next several sections discuss a number of quaternion operations from mathematical and geometric perspectives.

8.5.3Quaternion Negation

Quaternions can be negated. This is done in the obvious way of negating each component:

Quaternion negationThe surprising fact about negating a quaternion is that it really doesn't do anything, at least in the context of angular displacement.

It's not too difficult to see why this is true. If we add

8.5.4Identity Quaternion(s)

Geometrically, there are two “identity” quaternions that represent “no angular displacement.” They are

Identity quaternions

(Note the boldface zero, which indicates the zero vector.) When

Algebraically, there is really only one identity quaternion:

8.5.5Quaternion Magnitude

We can compute the magnitude of a quaternion, just as we can for vectors and complex numbers. The notation and formula shown in Equation (8.4) are similar to those used for vectors:

Quaternion magnitudeLet's see what this means geometrically for a rotation quaternion:

Rotation quaternions have unit magnitudeThis is an important observation.

For information concerning nonnormalized quaternions, see the technical report by Dam et al. [2].

8.5.6Quaternion Conjugate and Inverse

The conjugate of a quaternion, denoted

The term “conjugate” is inherited from the interpretation of a quaternion as a complex number. We look at this interpretation in more detail in Section 8.5.14.

The inverse of a quaternion, denoted

The quaternion inverse has an interesting correspondence with the multiplicative inverse for real

numbers (scalars). For real numbers, the multiplicative inverse

Equation (8.6) is the official definition of quaternion inverse. However, if you are interested only in quaternions that represent pure rotations, like we are in this book, then all the quaternions are unit quaternions and so the conjugate and inverse are equivalent.

The conjugate (inverse) is interesting because

For our purposes, an alternative definition of quaternion conjugate could have been to negate

8.5.7Quaternion Multiplication

Quaternions can be multiplied. The result is similar to the cross product for vectors, in that it yields another quaternion (not a scalar), and it is not commutative. However, the notation is different: we denote quaternion multiplication simply by placing the two operands side-by-side. The formula for quaternion multiplication can be easily derived based upon the definition of quaternions as complex numbers (see Exercise 6), but we state it here without development, using both quaternion notations:

Quaternion productThe quaternion product is also known as the Hamilton product; you'll understand why after reading about the history of quaternions in Section 8.5.14.

Let's quickly mention three properties of quaternion multiplication, all of which can be easily shown by using the definition given above. First, quaternion multiplication is associative, but not commutative:

Quaternion multiplication is associative, but not commutativeSecond, the magnitude of a quaternion product is equal to the product of the magnitudes (see Exercise 9):

Magnitude of quaternion productThis is very significant because it guarantees us that when we multiply two unit quaternions, the result is a unit quaternion.

Finally, the inverse of a quaternion product is equal to the product of the inverses taken in reverse order:

Inverse of quaternion product

Now that we know some basic properties of quaternion multiplication, let's talk about why the

operation is actually useful. Let us “extend” a standard 3D point

quaternion multiplication

Using quaternion multiplication to rotate a 3D vector

We could prove this by expanding the multiplication, substituting in

As it turns out, the correspondence between quaternion multiplication and 3D vector rotations is more of a theoretical interest than a practical one. Some people (“quaternio-philes?”) like to attribute quaternions with the useful property that vector rotations are immediately accessible by using Equation (8.7). To the quaternion lovers, we admit that this compact notation is an advantage of sorts, but its practical benefit in computations is dubious. If you actually work through this math, you will find that it is just about the same number of operations involved as converting the quaternion to the equivalent rotation matrix (by using Equation (8.20), which is developed in Section 8.7.3) and then multiplying the vector by this matrix. Because of this, we don't consider quaternions to possess any direct ability to rotate vectors, at least for practical purposes in acomputer.

Although the correspondence between

Notice that rotating by

We say “just like matrix multiplication,” but in fact there is a slightly irritating difference. With matrix multiplication, our preference to use row vectors puts the vectors on the left, resulting in the nice property that concatenated rotations read left-to-right in the order of transformation. With quaternions, we don't have this flexibility: concatenation of multiple rotations will always read “inside out” from right to left.12

8.5.8Quaternion “Difference”

Using the quaternion multiplication and inverse, we can compute the difference between two

quaternions, with “difference” meaning the angular displacement from one orientation to another.

In other words, given orientations

(Remember that quaternion multiplication performs the rotations from right-to-left.)

Let's solve for

Now we have a way to generate a quaternion that represents the angular displacement from one orientation to another. We use this in Section 8.5.12, when we explore slerp.

Mathematically, the angular difference between two quaternions is actually more similar to a division than a true difference (subtraction).

8.5.9Quaternion Dot Product

The dot product operation is defined for quaternions. The notation and definition for this operation is very similar to the vector dot product:

Quaternion dot product

Like the vector dot product, the result is a scalar. For unit quaternions

The dot product is perhaps not one of the most frequently used quaternion operators, at least in

video game programming, but it does have an interesting geometric interpretation. In

Section 8.5.8, we considered the difference quaternion

What does this mean geometrically? Remember Euler's rotation theorem: we can rotate from the

orientation

In summary, the quaternion dot product has an interpretation similar to the vector dot product. The

larger the absolute value of the quaternion dot product

Although direct use of the dot product is infrequent in most video game code, the dot product is the first step in the calculation of the slerp function, which we discuss in Section 8.5.12.

8.5.10Quaternion log, exp, and Multiplication by a Scalar

This section discusses three operations on quaternions that, although they are seldom used directly, are the basis for several important quaternion operations. These operations are the quaternion logarithm, exponential, and multiplication by a scalar.

First, let us reformulate our definition of a quaternion by introducing a variable

The logarithm of

We use the notation

The exponential function is defined in the exact opposite manner. First we define the quaternion

Then the exponential function is defined as

The exponential function of a quaternion

Note that, by definition,

The quaternion logarithm and exponential are related to their scalar analogs. For any scalar

In the same way, the quaternion exp function is defined to be the inverse of the quaternion log function:

Finally, quaternions can be multiplied by a scalar, with the result computed in the obvious way

of multiplying each component by the scalar. Given a scalar

This will not usually result in a unit quaternion, which is why multiplication by a scalar is not a very useful operation in the context of representing angular displacement. (But we will find a use for it in Section 8.5.11.)

8.5.11Quaternion Exponentiation

Quaternions can be exponentiated, which means that we can raise a quaternion to a scalar

power. Quaternion exponentiation, denoted

The meaning of quaternion exponentiation is similar to that of real numbers. Recall that for any

scalar

Quaternion exponentiation is useful because it allows us to extract a “fraction” of an angular

displacement. For example, to compute a quaternion that represents one third of the angular

displacement represented by the quaternion

Exponents outside the

The caveat we mentioned is this: a quaternion represents angular displacements using the shortest

arc. Multiple spins cannot be represented. Continuing our example above,

In some situations, we do care about the total amount of rotation, not just the end result. (The most important example is that of angular velocity.) In these situations, quaternions are not the correct tool for the job; use the exponential map (or its cousin, the axis-angle format) instead.

Now that we understand what quaternion exponentiation is used for, let's see how it is mathematically defined. Quaternion exponentiation is defined in terms of the “utility” operations we learned in the previous section. The definition is given by

Raising a quaternion to a powerNotice that a similar statement is true regarding exponentiation of a scalar:

It is not too difficult to understand why

// Quaternion (input and output)

float w,x,y,z;

// Input exponent

float exponent;

// Check for the case of an identity quaternion.

// This will protect against divide by zero

if (fabs(w) < .9999f) {

// Extract the half angle alpha (alpha = theta/2)

float alpha = acos(w);

// Compute new alpha value

float newAlpha = alpha * exponent;

// Compute new w value

w = cos(newAlpha);

// Compute new xyz values

float mult = sin(newAlpha) / sin(alpha);

x *= mult;

y *= mult;

z *= mult;

}

There are a few points to notice about this code. First, the check for the identity quaternion is

necessary since a value of

Second, when we compute alpha, we use the

8.5.12Quaternion Interpolation, a.k.a. Slerp

The raison d'être of quaternions in games and graphics today is an operation known as slerp, which stands for Spherical Linear interpolation. The slerp operation is useful because it allows us to smoothly interpolate between two orientations. Slerp avoids all the problems that plagued interpolation of Euler angles (see Section 8.3.4).

Slerp is a ternary operator, meaning it accepts three operands. The first two operands to slerp are

the two quaternions between which we wish to interpolate. We'll assign these starting and ending

orientations to the variables

Let's see if we can't derive the slerp formula by using the tools we have so far. If we were

interpolating between two scalar values

The standard linear interpolation formula works by starting at

- Compute the difference between the two values.

- Take a fraction of this difference.

- Take the original value and adjust it by this fraction of the difference.

We can use the same basic idea to interpolate between orientations. (Again, remember that quaternion multiplication reads right-to-left.)

-

Compute the difference between the two values. We showed how to do this in

Section 8.5.8. The angular displacement from

-

Take a fraction of this difference. To do this, we use quaternion

exponentiation, which we discussed in Section 8.5.11. The

fraction of the difference is given by

-

Take the original value and adjust it by this

fraction of the difference.

We “adjust” the initial value by

composing the angular displacements via quaternion multiplication:

Thus, the equation for slerp is given by

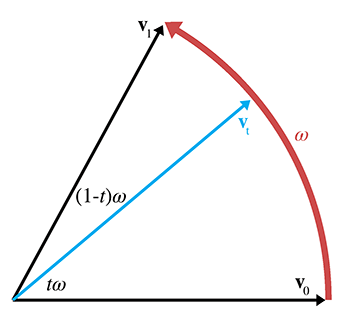

Quaternion slerp in theoryThis algebraic form is how slerp is computed in theory. In practice, we use a formulation that is mathematically equivalent, but computationally more efficient. To derive this alternative formula, we start by interpreting the quaternions as existing in a 4D Euclidian space. Since all of the quaternions of interest are unit quaternions, they “live” on the surface of a 4D hypersphere. The basic idea is to interpolate around the arc that connects the two quaternions, along the surface of the 4D hypersphere. (Hence the name spherical linear interpolation.)

We can visualize this in the plane (see Figure 8.11). Imagine two 2D vectors

We can express

Applying some trig to the right triangle with

A similar technique to solve for

Thus,

The same basic idea can be extended into quaternion space, and we can reformulate the slerp as

Quaternion slerp in practice

We just

need a way to compute

There are two slight complications. First, the two quaternions

// The two input quaternions

float w0,x0,y0,z0;

float w1,x1,y1,z1;

// The interpolation parameter

float t;

// The output quaternion will be computed here

float w,x,y,z;

// Compute the "cosine of the angle" between the

// quaternions, using the dot product

float cosOmega = w0*w1 + x0*x1 + y0*y1 + z0*z1;

// If negative dot, negate one of the input

// quaternions, to take the shorter 4D "arc"

if (cosOmega < 0.0f) {

w1 = -w1;

x1 = -x1;

y1 = -y1;

z1 = -z1;

cosOmega = -cosOmega;

}

// Check if they are very close together, to protect

// against divide-by-zero

float k0, k1;

if (cosOmega > 0.9999f) {

// Very close - just use linear interpolation

k0 = 1.0f-t;

k1 = t;

} else {

// Compute the sin of the angle using the

// trig identity sin^2(omega) + cos^2(omega) = 1

float sinOmega = sqrt(1.0f - cosOmega*cosOmega);

// Compute the angle from its sine and cosine

float omega = atan2(sinOmega, cosOmega);

// Compute inverse of denominator, so we only have

// to divide once

float oneOverSinOmega = 1.0f / sinOmega;

// Compute interpolation parameters

k0 = sin((1.0f - t) * omega) * oneOverSinOmega;

k1 = sin(t * omega) * oneOverSinOmega;

}

// Interpolate

w = w0*k0 + w1*k1;

x = x0*k0 + x1*k1;

y = y0*k0 + y1*k1;

z = z0*k0 + z1*k1;

8.5.13Advantages and Disadvantages of Quaternions

Quaternions offer a number of advantages over other methods of representing angular displacement:

- Smooth interpolation. The interpolation provided by slerp provides smooth interpolation between orientations. No other representation method provides for smooth interpolation.

- Fast concatenation and inversion of angular displacements. We can concatenate a sequence of angular displacements into a single angular displacement by using the quaternion cross product. The same operation using matrices involves more scalar operations, although which one is actually faster on a given architectures is not so clean-cut: single instruction multiple data (SIMD) vector operations can make very quick work of matrix multiplication. The quaternion conjugate provides a way to compute the opposite angular displacement very efficiently. This can be done by transposing a rotation matrix, but is not easy with Euler angles.

- Fast conversion to and from matrix form. As we see in Section 8.7, quaternions can be converted to and from matrix form a bit faster than Euler angles.

- Only four numbers. Since a quaternion contains four scalar values, it is considerably more economical than a matrix, which uses nine numbers. (However, it still is 33%larger than Euler angles.)

These advantages do come at some cost, however. Quaternions suffer from a few of the problems that affect matrices, only to a lesser degree:

-

Slightly bigger than Euler angles. That one additional number may not seem

like much, but an extra 33%can make a difference when large amounts of angular

displacements are needed, for example, when storing animation data. And the values

inside a quaternion are not “evenly spaced” along the

- Can become invalid. This can happen either through bad input data, or from accumulated floating point roundoff error. (We can address this problem by normalizing the quaternion to ensure that it has unit magnitude.)

- Difficult for humans to work with. Of the three representation methods, quaternions are the most difficult for humans to work with directly.

8.5.14Quaternions as Complex Numbers

We end our discussion on quaternions in the place that most texts begin: a discussion of their

interpretation as complex numbers. If you are interested in quaternions solely for rotations, you

can safely skip this section. If you want a bit deeper understanding or are interested in the

mathematical heritage of quaternions and the circumstances that surrounded their invention, this

section will be interesting. We will be following an approach due to John McDonald of DePaul

University [9]. Among other things, this method is able to

explain two peculiarities of quaternions: the appearance of

We begin by considering how we can embed the set of real numbers in the set of

We have chosen a subset of the

Now let's see if we can create a similar mapping for the set of complex numbers. You probably

already have been introduced to complex numbers; if so, you should remember that the complex pair

Complex numbers can be added, subtracted, and multiplied. All we need to do is follow the

ordinary rules for arithmetic, and replace

Now, how can we extend our system of embedding numbers in the space of

We can easily verify that the complex number on the left behaves exactly the same as the matrix on the right. In a certain sense, they are just two notations for writing the same quantity:

Addition, subtraction, and multiplication in standard notation and ourWe also verify that the equation

Let's apply the geometric perspective from Chapter 5. Interpreting the

columns14

There's nothing “imaginary” about this. Instead of thinking of

Continuing this further, we see that we can represent rotations by any arbitrary angle

Notice how complex conjugation (negating the complex part) corresponds to matrix transposition. This is particularly pleasing. Remember that the conjugate of a quaternion expresses the inverse angular displacement. A corresponding fact is true for transposing rotation matrices: since they are orthogonal, their transpose is equal to their inverse.

How do ordinary 2D vectors fit into this scheme? We interpret the vector

as performing a rotation. This is equivalent to the matrix multiplication

While this a not much more that mathematical trivia so far, our goal is to build up some parallels that we can carry forward to quaternions, so let's repeat the key result.

A similar conversion from ordinary vectors to complex numbers is necessary in order to multiply quaternions and 3D vectors.

Before we leave 2D, let's summarize what we've learned so far. Complex numbers are mathematical

objects with two degrees of freedom that obey certain rules when we multiply them. These objects

are usually written as

It's very tempting to extend this trick from 2D into 3D. Tempting, but alas not possible in the straightforward way. The Irish mathematician William Hamilton (1805–1865) apparently fell victim to just this temptation, and had looked for a way to extend complex numbers from 2D to 3D for years. This new type of complex number, he thought, would have one real part and two imaginary parts. However, Hamilton was unable to create a useful type of complex number with two imaginary parts. Then, as the story goes, in 1843, on his way to a speech at the Royal Irish Academy, he suddenly realized that three imaginary parts were needed rather than two. He carved the equations that define the properties of this new type of complex number on the Broom Bridge. His original marks have faded into legend, but a commemorative plaque holds their place. Thus quaternions were invented.

Since we weren't on the Broom Bridge in 1843, we can't say for certain what made Hamilton realize

that a 3D system of complex numbers was no good, but we can show how such a set could not be

easily mapped to

Quaternions extend the complex number system by having three imaginary numbers,

The quaternion we have been denoting

Now we return to matrices. Can we embed the set of quaternions into the set of matrices such that

Hamilton's rules in Equation (8.10) still hold? Yes, we can, although,

as you might expect, we map them to

and the complex quantities are mapped to the matrices

Mapping the three complex quantities toWe encourage you to convince yourself that these mappings do preserve all of Hamilton's rules before moving on.

Combining the above associations, we can map an arbitrary quaternion to a

Once again, we notice how complex conjugation (negating

Everything we've said so far applies to quaternions of any length. Now let's get back to

rotations. We can see that the

which corresponds to

This result does not correspond to a vector at all, since it has a nonzero value for

The upper-left

Now we are left wondering if maybe we did something wrong. Perhaps there are other

Comparing this to Equation (8.13), when the operands were in the opposite

order, we see that the only difference is the sign of the

So, multiplying on the left by

Before we leave this section, let us go back and clear up one last finer point. We mentioned that

there are other ways we could embed the set of quaternions within the set of

8.5.15Summary of Quaternions

Section 8.5 has covered a lot of math, and most of it isn't important to remember. The facts that are important to remember about quaternions are summarized here.

- Conceptually, a quaternion expresses angular displacement by using an axis of rotation and an amount of rotation about that axis.

-

A quaternion contains a scalar component

- Every angular displacement in 3D has exactly two different representations in quaternion space, and they are negatives of each other.

-

The identity quaternion, which represents “no angular displacement,” is

- All quaternions that represent angular displacement are “unit quaternions” with magnitude equal to 1.

-

The conjugate of a quaternion expresses the opposite angular displacement and is

computed by negating the vector portion

- Quaternion multiplication can be used to concatenate multiple rotations into a single angular displacement. In theory, quaternion multiplication can also be used to perform 3D vector rotations, but this is of little practical value.

- Quaternion exponentiation can be used to calculate a multiple of an angular displacement. This always captures the correct end result; however, since quaternions always take the shortest arc, multiple revolutions cannot be represented.

- Quaternions can be interpreted as 4D complex numbers, which creates interesting and elegant parallels between mathematics and geometry.

A lot more has been written about quaternions than we have had the space to discuss here. The technical report by Dam et al [2] is a good mathematical summary. Kuiper's book [8] is written from an aerospace perspective and also does a good job of connecting quaternions and Euler angles. Hanson's modestly titled Visualizing Quaternions [6] analyzes quaternions using tools from several different disciplines (Riemannian Geometry, complex numbers, lie algebra, moving frames) and is sprinkled with interesting engineering and mathematical lore; it also discusses how to visualize quaternions. A shorter presentation on visualizing quaternions is given by Hart et al. [7].

8.6Comparison of Methods

Let's review the most important discoveries from the previous sections. Table 8.1 summarizes the differences among the three representation methods.

-

Rotating points between coordinate spaces (object and upright)

- Matrix: Possible; can often by highly optimized by SIMD instructions.

- Euler Angles: Impossible (must convert to rotation matrix).

- Exponential Map: Impossible (must convert to rotation matrix).

- Quaternion: On a chalkboard, yes. Practically, in a computer, not really. You might as well convert to rotation matrix.

-

Concatenation of multiple rotations

- Matrix: Possible; can often be highly optimized by SIMD instructions. Watch out for matrix creep.

- Euler Angles: Impossible.

- Exponential Map: Impossible.

- Quaternion: Possible. Fewer scalar operations than matrix multiplication, but maybe not as easy to take advantage of SIMD instructions. Watch out for error creep.

-

Inversion of rotations

- Matrix: Easy and fast, using matrix transpose.

- Euler Angles: Not easy.

- Exponential Map: Easy and fast, using vector negation.

- Quaternion: Easy and fast, using quaternion conjugate.

-

Interpolation

- Matrix: Extremely problematic.

- Euler Angles: Possible, but Gimbal lock causes quirkiness.

- Exponential Map: Possible, with some singularities, but not as troublesome as Euler angles.

- Quaternion: Slerp provides smooth interpolation.

-

Direct human interpretation

- Matrix: Difficult.

- Euler Angles: Easiest.

- Exponential Map: Very difficult.

- Quaternion: Very difficult.

-

Storage efficiency in memory or in a file

- Matrix: Nine numbers.

- Euler Angles: Three numbers that can be easily quantized.

- Exponential Map: Three numbers that can be easily quantized.

- Quaternion: Four numbers that do not quantize well; can be reduced to three by assuming fourth component is always nonnegative and quaternion has unit length.

-

Unique representation for a given rotation

- Matrix: Yes.

- Euler Angles: No, due to aliasing.

- Exponential Map: No, due to aliasing, but not as complicated as Euler angles.

- Quaternion: Exactly two distinct representations for any angular displacement, and they are negatives of each other.

-

Possible to become invalid

- Matrix: Six degrees of redundancy inherent in orthogonal matrix. Matrix creep can occur.

- Euler Angles: Any three numbers can be interpreted unambiguously.

- Exponential Map: Any three numbers can be interpreted unambiguously.

- Quaternion: Error creep can occur.

Some situations are better suited for one orientation format or another. The following advice should aid you in selecting the best format:

- Euler angles are easiest for humans to work with. Using Euler angles greatly simplifies human interaction when specifying the orientation of objects in the world. This includes direct keyboard entry of an orientation, specifying orientations directly in the code (i.e., positioning the camera for rendering), and examination in the debugger. This advantage should not be underestimated. Certainly don't sacrifice ease of use in the name of “optimization” until you are certain that it will make a difference.

- Matrix form must eventually be used if vector coordinate space transformations are needed. However, this doesn't mean you can't store the orientation in another format and then generate a rotation matrix when you need it. A common strategy is to store the “main copy” of an orientation in Euler angle or quaternion form, but also to maintain a matrix for rotations, recomputing this matrix any time the Euler angles or quaternion change.

- For storage of large numbers of orientations (e.g., animation data), Euler angles, exponential maps, and quaternions offer various tradeoffs. In general, the components of Euler angles and exponential maps quantize better than quaternions. It is possible to store a rotation quaternion in only three numbers. Before discarding the fourth component, we check its sign; if it's negative, we negate the quaternion. Then the discarded component can be recovered by assuming the quaternion has unit length.

- Reliable quality interpolation can be accomplished only by usingquaternions. Even if you are using a different form, you can always convert to quaternions, perform the interpolation, and then convert back to the original form. Direct interpolation using exponential maps might be a viable alternative in some cases, as the points of singularity are at very extreme orientations and in practice are often easily avoided.

- For angular velocity or any other situation where “extra spins” need to be represented, use the exponential map or axis-angle.

8.7Converting between Representations

We have established that different methods of representing orientation are appropriate in different situations, and have also provided some guidelines for choosing the most appropriate method. This section discusses how to convert an angular displacement from one format to another. It is divided into six subsections:

- Section 8.7.1 shows how to convert Euler angles to a matrix.

- Section 8.7.2 shows how to convert a matrix to Euler angles.

- Section 8.7.3 shows how to convert a quaternion to a matrix.

- Section 8.7.4 shows how to convert a matrix to a quaternion.

- Section 8.7.5 shows how to convert Euler angles to a quaternion.

- Section 8.7.6 shows how to convert a quaternion to Euler angles.

For more on converting between representation forms, see the paper by James Diebel [3].

8.7.1Converting Euler Angles to a Matrix

Euler angles define a sequence of three rotations. Each of these three rotations is a simple rotation about a cardinal axis, so each is easy to convert to matrix form individually. We can compute the matrix that defines the total angular displacement by concatenating the matrices for each individual rotation. This exercise is carried out in numerous books and websites. If you've ever tried to use one of these references, you may have been left wondering, “Exactly what happens if I multiply a vector by this matrix?” The reason for your confusion is because they forgot to mention whether the matrix rotates from object space to upright space or from upright space to object space. In other words, there are actually two different matrices, not just one. (Of course, they are transposes of each other, so, in a sense, there really is only one matrix.) This section shows how to compute both.

Some readers16 might think that we are belaboring the point. Maybe you figured out how to use that rotation matrix from that book or website, and now it's totally obvious to you. But we've seen this be a stumbling block for too many programmers, so we have chosen to dwell on this point. One common example will illustrate the confusion we've seen.