Triangle man hates particle man.

They have a fight, triangle wins.

Triangle man.

This chapter is about geometric primitives in general and in specific.

- Section 9.1 discusses some general principles related to representing geometric primitives.

- Sections 9.2–9.7 cover a number of specific important geometric primitives, including methods for representing those primitives and some classic properties and operations. Along the way, we'll present a few C++ snippets.

9.1Representation Techniques

Let's begin with a brief overview of the major strategies for describing geometric shapes. For any given primitive, one or more of these techniques may be applicable, and different techniques are useful in different situations.

We can describe an object in implicit form by defining a Boolean

function

is true for all points on the surface of a unit sphere centered at the origin. The conic

sections are classic examples of implicit representations of geometric shapes that you may

already know. A conic section is a 2D shape formed by the intersection of a cone with a plane.

The conic sections are the circle, ellipse, parabola, and hyperbola, all of which can be

described in the standard implicit form

Metaballs [1] is an implicit method for representing fluid and organic shapes. The volume is defined by a collection of fuzzy “balls.” Each ball defines a three-dimensional scalar density function based on the distance from the center of the ball, with zero distance being the maximal value and greater distances having lower values. We can define an aggregate density function for any arbitrary point in space by taking the sum of the density of all the balls at that point. The twist with metaballs is that the volume of the fluid or organic object is defined to be the region where the density exceeds some nonzero threshold. In other words, the balls have a “fuzzy” region around them that extends outside of the volume when the ball is in isolation. When two or more balls come together, the fuzzy regions interfere constructively, causing a graceful “bond” of solid volume to materialize in the region in between the balls, where no such solid would exist if either ball were in isolation. The marching cubes algorithm [5] is a classic technique for converting an arbitrary implicit form into a surface description (such as a polygon mesh).

Another general strategy for describing shapes is the parametric form. Once again, the

primitive is defined by a function, but instead of the spatial coordinates being the input to the

function, they are the output. Let's begin with a simple 2D example. We define the following two

functions of

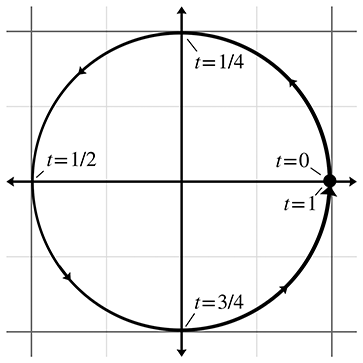

The argument

It is often convenient to normalize the parameter to be in the range

When our functions are in terms of one parameter, we say that the functions are

univariate. Univariate functions trace out a 1D shape: a curve. (Chapter 13

presents more about parametric curves.) It's also possible to use more than one parameter. A

bivariate function accepts two parameters, usually assigned to the variables

We have dubbed the final method for representing primitives, for lack of a better term, straightforward forms. By this we mean all the ad-hoc methods that capture the most important and obvious information directly. For example, to describe a line segment, we could name the two endpoints. A sphere is described most simply by giving its center and radius. The straightforward forms are the easiest for humans to work with directly.

Regardless of the method of representation, each geometric primitive has an inherent number of

degrees of freedom. This is the minimum number of “pieces of information” that are required to

describe the entity unambiguously. It is interesting to notice that for the same geometric

primitive, some representation forms use more numbers than others. However, we find that any

“extra” numbers are always due to a redundancy in the parameterization of the primitive, which

could be eliminated by assuming the appropriate constraint, such as a vector having unit length.

For example, a circle in the plane has three degrees of freedom: two for the position of the

center

However, the general conic section equation (the implicit form) is

9.2Lines and Rays

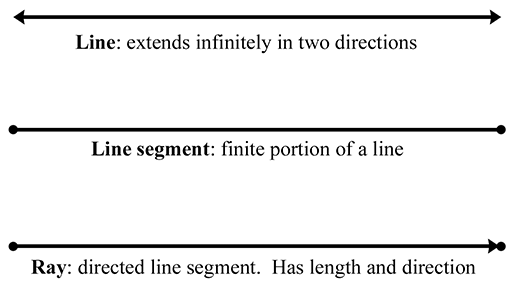

Now for some specific types of primitives. We begin with what is perhaps the most basic and important one of all: the linear segment. Let's meet the three basic types of linear segments, and also clarify some terminology. In classical geometry, the following definitions are used:

- A line extends infinitely in two directions.

- A line segment is a finite portion of a line that has two endpoints.

- A ray is “half” of a line that has an origin and extends infinitely in one direction.

In computer science and computational geometry, there are variations on these definitions. This book uses the classical definitions for line and line segment. However, the definition of “ray” is altered slightly:

- A ray is a directed line segment.

So to us, a ray will have an origin and an endpoint. Thus a ray defines a position, a finite length, and (unless the ray has zero length) a direction. Since a ray is just a line segment where we have differentiated between the two ends, and a ray also can be used to define an infinite line, rays are of fundamental importance in computational geometry and graphics and will be the focus of this section. A ray can be imagined as the result of sweeping a point through space over time; rays are everywhere in video games. An obvious example is the rendering strategy known as raytracing, which uses eponymous rays representing the paths of photons. For AI, we trace “line of sight” rays through the environment to detect whether an enemy can see the player. Many user interface tools use raytracing to determine what object is under the mouse cursor. Bullets and lasers are always whizzing through the air in video games, and we need rays to determine what they hit. Figure 9.2 compares the line, line segment, and ray.

The remainder of this section surveys different methods for representing lines and rays in 2D and 3D. Section 9.2.1 discusses some simple ways to represent a ray, including the all-important parametric form. Section 9.2.2 discusses some special ways to define an infinite line in 2D. Section 9.2.3 gives some examples of converting from one representation to another.

9.2.1Rays

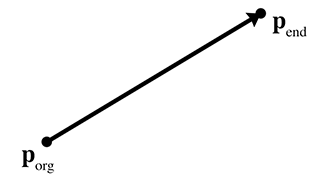

The most obvious way to define a ray (the “straightforward form”) is by two points, the ray

origin and the ray endpoint, which we will denote as

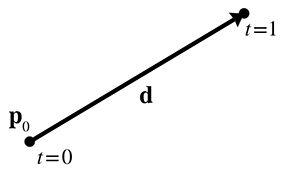

The parametric form of the ray is only slightly different, and is quite important:

Parametric definition of a ray using vector notation

The ray starts at the point

We can also write out a separate scalar function for each coordinate, although the vector format is more compact and also has the nice property that it makes the equations the same in any dimension. For example, a 2D ray is defined parametrically by using the two scalar functions,

Parametric definition of a 2D ray

A slight variation on Equation (9.1) that we use in some of the intersection

tests is to use a unit vector

9.2.2Special 2D Representations of Lines

Now let's look a bit closer at some special ways of describing (infinite) lines. These methods

are applicable only in 2D; in 3D, techniques similar to these are used to define a plane, as we

show in Section 9.5. A 2D ray inherently has four degrees of freedom (

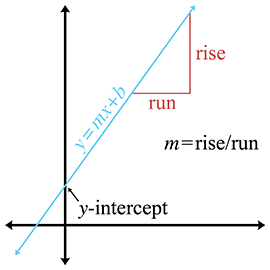

Most readers are probably familiar with the slope-intercept form, which is an implicit method for representing an infinite line in 2D:

Slope-intercept form

The symbol

The slope-intercept makes it easy to verify that an infinite line does, in fact, have two degrees

of freedom: one degree for rotation and another for translation. Unfortunately, a vertical line

has infinite slope and cannot be represented in slope-intercept form, since the implicit form of

a vertical line is

We can work around this singularity by using the slightly different implicit form

Implicit definition of infinite line in 2D

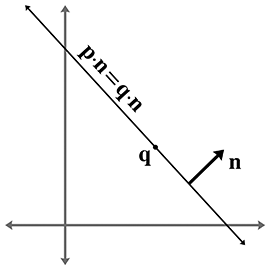

If we assign the vector

Since this form has three degrees of freedom, and we said that an infinite line in 2D has only

two, we know there is some redundancy. Note that we can multiply both sides of the equation by

any constant; by so doing, we are free to choose the length of

The vector

Notice that

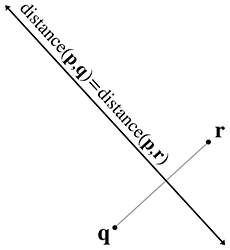

One final way to define a line is as the perpendicular bisector of two points, to which we assign

the variables

9.2.3Converting between Representations

Now let's give a few examples of how to convert a ray or line between the various representation techniques. We will not cover all of the combinations. Remember that the techniques we learned for infinite lines are applicable only in 2D.

To convert a ray defined using two points to parametric form:

The opposite conversion, from parametric form to two-points form, is

Given a parametric ray, we can compute the implicit line that contains this ray:

To convert a line expressed implicitly to slope-intercept form:

Converting a line expressed implicitly to “normal and distance” form:

Converting a normal and a point on the line to normal and distance form:

(This assumes that

Finally, to convert perpendicular bisector form to implicit form, we use

9.3Spheres and Circles

A sphere is a 3D object defined as the set of all points that are a fixed distance from a given

point. The distance from the center of the sphere to a point is known as the radius of the

sphere. The straightforward representation of a sphere is to describe its center

Spheres appear often in computational geometry and graphics because of their simplicity. A bounding sphere is often used for trivial rejection because the equations for intersection with a sphere are simple. Also important is that rotating a sphere does not change its extents. Thus, when a bounding sphere is used for trivial rejection, if the center of the sphere is the origin of the object, then the orientation of the object can be ignored. A bounding box (see Section 9.4) does not have this property.

The implicit form of a sphere comes directly from its definition:

the set of all points that are a given distance from the center. The

implicit form of a sphere with center

where

We might be interested in the diameter (distance from one point to a point on the exact opposite side), and circumference (the distance all the way around the circle) of a circle or sphere. Elementary geometry provides formulas for those quantities, as well as for the area of a circle, surface area of a sphere, and volume of a sphere:

For the calculus buffs, it is interesting to notice that the derivative of the area of a circle

with respect to

9.4Bounding Boxes

Another simple geometric primitive commonly used as a bounding volume is the bounding box. Bounding boxes may be either axially aligned, or arbitrarily oriented. Axially aligned bounding boxes have the restriction that their sides be perpendicular to principal axes. The acronym AABB is often used for axially aligned bounding box.

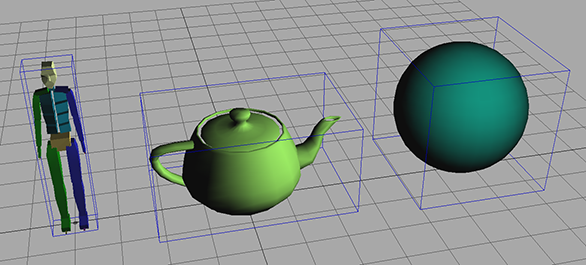

A 3D AABB is a simple 6-sided box with each side parallel to one of the cardinal planes. The box is not necessarily a cube—the length, width, and height of the box may each be different. Figure 9.9 shows a few simple 3D objects and their axially aligned bounding boxes.

Another frequently used acronym is OBB, which stands for oriented bounding box. We don't discuss OBBs much in this section, for two reasons. First, axially aligned bounding boxes are simpler to create and use. But more important, you can think about an OBB as simply an AABB with an orientation; every bounding box is an AABB in some coordinate space; in fact any one with axes perpendicular to the sides of the box will do. In other words, the difference between an AABB and an OBB is not in the box itself, but in whether you are performing calculations in a coordinate space aligned with the bounding box.

As an example, let's say that for objects in our world, we store the AABB of the object in the objects' object space. When performing operations in object space, this bounding box is an AABB. But when performing calculations in world (or upright) space, then this same bounding box is an OBB, since it may be “at an angle” relative to the world axes.

Although this section focuses on 3D AABBs, most of the information can be applied in a straightforward manner in 2D by simply dropping the third dimension.

The next four sections cover the basic properties of AABBs. Section 9.4.1 introduces the notation we use and describes the options we have for representing an AABB. Section 9.4.2 shows how to compute the AABB for a set of points. Section 9.4.3 compares AABBs to bounding spheres. Section 9.4.4 shows how to construct an AABB for a transformed AABB.

9.4.1Representing AABBs

Let us introduce several important properties of an AABB, and the notation we use when referring to these values. The points inside an AABB satisfy the inequalities

Two corner points of special significance are

The center point

The “size vector”

We can also refer to the “radius vector”

To unambiguously define an AABB requires only two of the five vectors

struct AABB3 {

Vector3 min;

Vector3 max;

};

9.4.2Computing AABBs

void AABB3::empty() {

min.x = min.y = min.z = FLT_MAX;

max.x = max.y = max.z = -FLT_MAX;

}

void AABB3::add(const Vector3 &p) {

if (p.x < min.x) min.x = p.x;

if (p.x > max.x) max.x = p.x;

if (p.y < min.x) min.y = p.y;

if (p.y > max.x) max.y = p.y;

if (p.z < min.x) min.z = p.z;

if (p.z > max.x) max.z = p.z;

}

Computing an AABB for a set of points is a simple process. We first reset the minimum and maximum values to “infinity,” or what is effectively bigger than any number we will encounter in practice. Then, we pass through the list of points, expanding our box as necessary to contain each point.

An AABB class often defines two functions to help with this. The first function “empties” the AABB. The other function adds a single point into the AABB by expanding the AABB if necessary to contain the point. Listing 9.2 shows such code.

Now, to create a bounding box from a set of points, we could use the following code:

// Our list of points

const int N;

Vector3 list[N];

// First, empty the box

AABB3 box;

box.empty();

// Add each point into the box

for (int i = 0 ; i < N ; ++i) {

box.add(list[i]);

}

9.4.3AABBs versus Bounding Spheres

In many cases, we have a choice between using an AABB or a bounding sphere. AABBs offer two main advantages over bounding spheres.

The first advantage of AABBs over bounding spheres is that computing the optimal AABB for a set of points is easy to program and can be run in linear time. Computing the optimal bounding sphere is a much more difficult problem. (O'Rourke [6] and Lengyel [4] describe algorithms for computing bounding spheres.)

Second, for many objects that arise in practice, an AABB provides a tighter bounding volume, and thus better trivial rejection. Of course, for some objects, the bounding sphere is better. (Imagine an object that is itself a sphere!) In the worst case, an AABB will have a volume of just under twice the volume of the sphere, but when a sphere is bad, it can be really bad. Consider the bounding sphere and AABB of a telephone pole, for example.

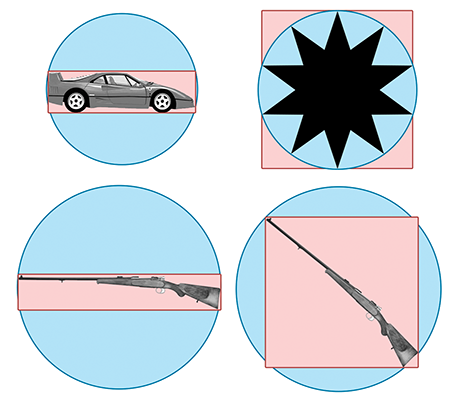

The basic problem with a sphere is that there is only one degree of freedom to its shape—the radius of the sphere. An AABB has three degrees of freedom—the length, width, and height. Thus, it can usually adapt to differently shaped objects better. For most of the objects in Figure 9.10, the AABB is smaller than the bounding sphere. The exception is the star in the upper right-hand corner, where the bounding sphere is slightly smaller than the AABB. Notice that the AABB is highly sensitive to the orientation of the object, as shown by the AABBs for the two rifles on the bottom. In each case, the size of the rifle is the same, and only the orientation is different. Also notice that the bounding spheres are the same size since bounding spheres are not sensitive to the orientation of the object. When the objects are free to rotate, some of the advantage of AABBs can be eroded. There is an inherent trade-off between a tighter volume (OBB) and a compact, fast representation (bounding spheres). Which bounding primitive is best will depend highly on the application.

9.4.4Transforming AABBs

Sometimes we need to transform an AABB from one coordinate space to another. For example, let's say that we have the AABB in object space (which, from the perspective of world space, is basically the same thing as an OBB; see Section 9.4) and we want to get an AABB in world space. Of course, in theory, we could compute a world-space AABB of the object itself. However, we assume that the description of the object shape (perhaps a triangle mesh with a thousand vertices) is more complicated than the AABB that we already have computed in object space. So to get an AABB in world space, we will transform the object-space AABB.

What we get as a result is not necessarily axially aligned (if the object is rotated), and is not necessarily a box (if the object is skewed). However, computing an AABB for the “transformed AABB” (we should perhaps call it a NNAABNNB—a “not-necessarily axially aligned bounding not-necessarily box”) is faster than computing a new AABB for all but the most simple transformed objects because AABBs have only eight vertices.

To compute an AABB for a transformed AABB it is not enough to simply transform the

original

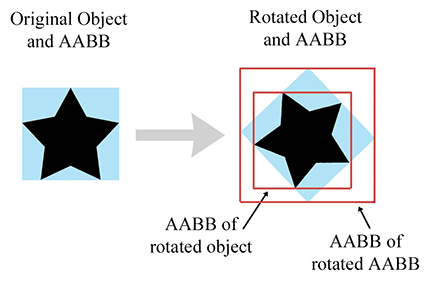

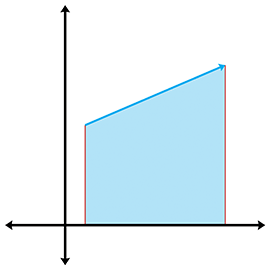

Depending on the transformation, this usually results in a bounding box that is larger than the original bounding box. For example, in 2D, a rotation of 45 degrees will increase the size of the bounding box significantly (see Figure 9.11).

Compare the size of the original AABB in Figure 9.11 (the blue box), with the new AABB (the largest red box on the right) which was computed solely from the rotated AABB. The new AABB is almost twice as big. Notice that if we were able to compute an AABB from the rotated object rather than the rotated AABB, it is about the same size as the original AABB.

As it turns out, the structure of an AABB can be exploited to speed up the generation of the new AABB, so it is not necessary to actually transform all eight corner points and build a new AABB from these points.

Let's quickly review what happens when we transform a

3D point by a

Assume the original bounding box is in

where

This technique is illustrated in Listing 9.4. The class

Matrix4x3 is a

void AABB3::setToTransformedBox(const AABB3 &box, const Matrix4x3 &m) {

// Start with the last row of the matrix, which is the translation

// portion, i.e. the location of the origin after transformation.

min = max = getTranslation(m);

//

// Examine each of the 9 matrix elements

// and compute the new AABB

//

if (m.m11 > 0.0f) {

min.x += m.m11 * box.min.x; max.x += m.m11 * box.max.x;

} else {

min.x += m.m11 * box.max.x; max.x += m.m11 * box.min.x;

}

if (m.m12 > 0.0f) {

min.y += m.m12 * box.min.x; max.y += m.m12 * box.max.x;

} else {

min.y += m.m12 * box.max.x; max.y += m.m12 * box.min.x;

}

if (m.m13 > 0.0f) {

min.z += m.m13 * box.min.x; max.z += m.m13 * box.max.x;

} else {

min.z += m.m13 * box.max.x; max.z += m.m13 * box.min.x;

}

if (m.m21 > 0.0f) {

min.x += m.m21 * box.min.y; max.x += m.m21 * box.max.y;

} else {

min.x += m.m21 * box.max.y; max.x += m.m21 * box.min.y;

}

if (m.m22 > 0.0f) {

min.y += m.m22 * box.min.y; max.y += m.m22 * box.max.y;

} else {

min.y += m.m22 * box.max.y; max.y += m.m22 * box.min.y;

}

if (m.m23 > 0.0f) {

min.z += m.m23 * box.min.y; max.z += m.m23 * box.max.y;

} else {

min.z += m.m23 * box.max.y; max.z += m.m23 * box.min.y;

}

if (m.m31 > 0.0f) {

min.x += m.m31 * box.min.z; max.x += m.m31 * box.max.z;

} else {

min.x += m.m31 * box.max.z; max.x += m.m31 * box.min.z;

}

if (m.m32 > 0.0f) {

min.y += m.m32 * box.min.z; max.y += m.m32 * box.max.z;

} else {

min.y += m.m32 * box.max.z; max.y += m.m32 * box.min.z;

}

if (m.m33 > 0.0f) {

min.z += m.m33 * box.min.z; max.z += m.m33 * box.max.z;

} else {

min.z += m.m33 * box.max.z; max.z += m.m33 * box.min.z;

}

}

9.5Planes

A plane is a flat, 2D subspace of 3D. Planes are extremely common tools in video games, and the concepts in this section are especially useful. The definition of a plane that Euclid would probably recognize is similar to the perpendicular bisector definition of an infinite line in 2D: the set of all points that are equidistant from two given points. This similarity in definitions hints at the fact that planes in 3D share many properties with infinite lines in 2D. For example, they both subdivide the space into two “half-spaces.”

This section covers the fundamental properties of planes. Section 9.5.1 shows how to define a plane implicitly with the plane equation. Section 9.5.2 shows how three points may be used to define a plane. Section 9.5.3 describes how to find the “best-fit” plane for a set of points that may not be exactly planar. Section 9.5.4 describes how to compute the distance from a point to a plane.

9.5.1The Plane Equation: An Implicit Definition of a Plane

We can represent planes using techniques similar to the ones we used to describe infinite 2D

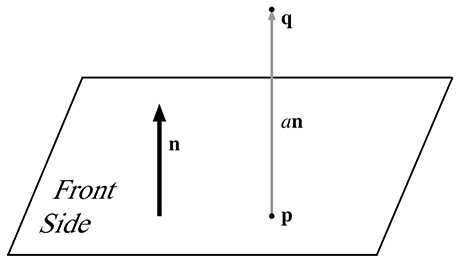

lines in Section 9.2.2. The implicit form of a plane is given by all points

Note that in the vector form,

The vector

Let's verify that

The geometric implication of Equation (9.11) is that

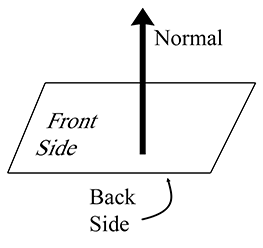

We often consider a plane as having a “front” side and a “back” side. Usually, the front side

of the plane is the direction that

As mentioned previously, it's often useful to restrict

9.5.2Defining a Plane by Using Three Points

Another way we can define a plane is to give three noncollinear points that lie in the plane. Collinear points (points in a straight line) won't work because there would be an infinite number of planes that contain that line, and there would be no way of telling which plane we meant.

Let's compute

We will construct two vectors according to the clockwise ordering. The notation

Notice that if the points are collinear, then

Now that we know

9.5.3“Best Fit” Plane for More than Three Points

Occasionally, we may wish to compute the plane equation for a set of more than three points. The most common example of such a set of points is the vertices of a polygon. In this case, the vertices are assumed to be enumerated in a clockwise fashion around the polygon. (The ordering matters because it is how we decide which side is the front and which is the back, which in turn determines which direction our normal will point.)

One naïve solution is to arbitrarily select three consecutive points and compute the plane

equation from those three points. However, the three points we choose might be collinear, or

nearly collinear, which is almost as bad because it is numerically inaccurate. Or perhaps the

polygon is concave and the three points we have chosen are a point of concavity and therefore

form a counterclockwise turn (which would result in a normal that points in the wrong direction).

Or the vertices of the polygon may not be coplanar, which can happen due to numeric imprecision

or the method used to generate the polygon. What we really want is a way to compute the “best

fit” plane for a set of points that takes into account all of the points. Given

the best fit perpendicular vector

This vector must then be normalized if we wish to enforce the restriction that

We can express Equation (9.13) succinctly by using summation

notation. Adopting a circular indexing scheme such that

Listing 9.5 illustrates how we might compute a best-fit plane normal for a set of points.

Vector3 computeBestFitNormal(const Vector3 v[], int n) {

// Zero out sum

Vector3 result = kZeroVector;

// Start with the ``previous'' vertex as the last one.

// This avoids an if-statement in the loop

const Vector3 *p = &v[n-1];

// Iterate through the vertices

for (int i = 0 ; i < n ; ++i) {

// Get shortcut to the ``current'' vertex

const Vector3 *c = &v[i];

// Add in edge vector products appropriately

result.x += (p->z + c->z) * (p->y - c->y);

result.y += (p->x + c->x) * (p->z - c->z);

result.z += (p->y + c->y) * (p->x - c->x);

// Next vertex, please

p = c;

}

// Normalize the result and return it

result.normalize();

return result;

}

The best-fit

9.5.4Distance from Point to Plane

It is often the case that we have a plane and a point

If we assume the plane normal

9.6Triangles

Triangles are of fundamental importance in modeling and graphics. The surface of a complex 3D object, such as a car or a human body, is approximated with many triangles. Such a group of connected triangles forms a triangle mesh, which is the topic of Section 10.4. But before we can learn how to manipulate many triangles, we must first learn how to manipulate one triangle.

This section covers the fundamental properties of triangles. Section 9.6.1 introduces some notation and basic properties of triangles. Section 9.6.2 lists several methods for computing the area of a triangle in 2D or 3D. Section 9.6.3 discusses barycentric space. Section 9.6.5 discusses a few points on a triangle that are of special geometric significance.

9.6.1Notation

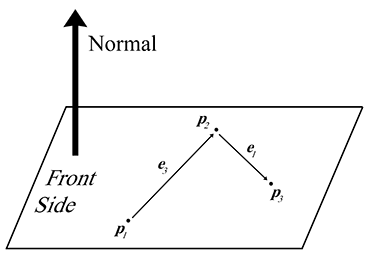

A triangle is defined by listing its three vertices. The order that these points are listed is

significant. In a left-handed coordinate system, we typically enumerate the points in clockwise

order when viewed from the front side of the triangle. We will refer to the three vertices as

A triangle lies in a plane, and the equation of this plane (the normal

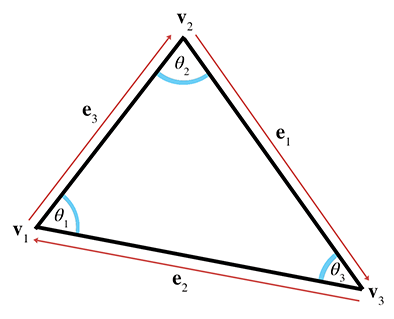

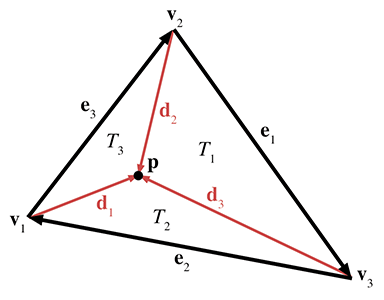

Let us label the interior angles, clockwise edge vectors, and side lengths as shown in Figure 9.15.

Let

For example, let's write the law of sines and law of cosines using this notation:

Law of sinesThe perimeter of the triangle is often an important value, and is computed trivially by summing the three sides:

Perimeter of a triangle9.6.2Area of a Triangle

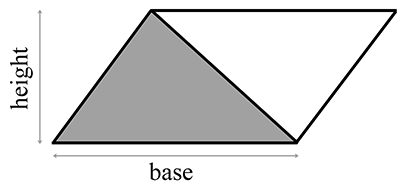

This section investigates several techniques for computing the area of a triangle. The most well known method is to compute the area from the base and height (also known as the altitude). Examine the parallelogram and enclosed triangle in Figure 9.16.

From classical geometry, we know that the area of a parallelogram is equal to the product of the base and height. (See Section 2.12.2 for an explanation of why this is true.) Since the triangle occupies exactly one half of this area, the area of a triangle, is

Area of a triangleIf the altitude is not known, then Heron's formula can be used, which requires only the

lengths of the three sides. Let

Heron's formula is particularly interesting because of the ease with which it can be applied in 3D.

Often the altitude or lengths of the sides are not readily available and all we have are the Cartesian coordinates of the vertices. (Of course, we could always compute the side lengths from the coordinates, but there are situations for which we wish to avoid this relatively costly computation.) Let's see if we can compute the area of a triangle from the vertex coordinatesalone.

Let's first tackle this problem in 2D. The basic idea is to compute, for each of the three edges

of the triangle, the signed area of the trapezoid bounded above by the edge and below by the

By summing the signed areas of the three trapezoids, we arrive at the area of the triangle itself. In fact, the same idea can be used to compute the area of a polygon with any number of sides.

We assume a clockwise ordering of the vertices around the triangle. Enumerating the vertices in the opposite order flips the sign of the area. With these considerations in mind, we sum the areas of the trapezoids to compute the signed area of the triangle:

We can actually simplify this just a bit further. The basic idea is to realize that we can

translate the triangle without affecting the area. We make an arbitrary choice to shift the

triangle vertically, subtracting

In 3D, we can use the cross product to compute the area of a triangle. Recall from

Section 2.12.2 that the magnitude of the cross product of two

vectors

Notice that if we extend a 2D triangle into 3D by assuming

9.6.3Barycentric Space

Even though we certainly use triangles in 3D, the surface of a triangle lies in a plane and is inherently a 2D object. Moving around on the surface of a triangle that is arbitrarily oriented in 3D is somewhat awkward. It would be nice to have a coordinate space that is related to the surface of the triangle and is independent of the 3D space in which the triangle “lives.” Barycentric space is just such a coordinate space. Many practical problems that arise when making video games, such as interpolation and intersection, can be solved by using barycentric coordinates. We are introducing barycentric coordinates in the context of triangles here, but they have wide applicability. In fact, we meet them again in a slightly more general form in the context of 3D curves in Chapter 13.

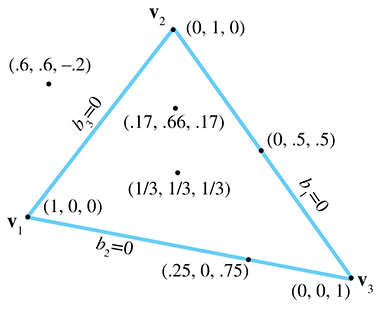

Any point in the plane of a triangle can be expressed as a weighted average of the vertices.

These weights are known as barycentric coordinates. The conversion from barycentric

coordinates

Of course, this is simply a linear combination of some vectors. Section 3.3.3 showed how ordinary Cartesian coordinates can also be interpreted as a linear combination of the basis vectors, but the subtle distinction between barycentric coordinates and ordinary Cartesian coordinates is that for barycentric coordinates the sum of the coordinates is restricted to be unity:

This normalization constraint removes one degree of freedom, which is why even though there are three coordinates, it is still a 2D space.

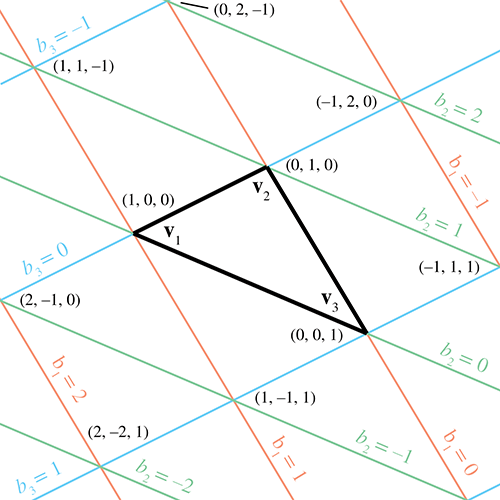

The values

Let's make a few observations here. First, notice that the three vertices of the triangle have a trivial form in barycentric space:

Second, all points on the side opposite a vertex will have a zero for the barycentric coordinate

corresponding to that vertex. For example,

Finally, any point in the plane can be described in barycentric coordinates, not just the

points inside the triangle. The barycentric coordinates of a point inside the triangle will all

be in the range

There's another way to think about barycentric coordinates. Discarding

This makes it very clear that, due to the normalization constraint, although there are three coordinates, there are only two degrees of freedom. We could completely describe a point in barycentric space using only two of the coordinates. In fact, the rank of the space described by the coordinates doesn't depend on the dimension of the “sample points” but rather on the number of sample points. The number of degrees of freedom is one less than the number of barycentric coordinates, since we have the constraint that the coordinates sum to one. For example, if we have two sample points, the dimension of the barycentric coordinates is two, and the space that can be described using these coordinates is a line, which is a 1D space. Notice that the line may be a 1D line (i.e., interpolation of a scalar), a 2D line, a 3D line, or a line in some higher dimensional space. In this section, we've had three sample points (the vertices of our triangle) and three barycentric coordinates, resulting in a 2D space—a plane. If we had four sample points in 3D, then we could use barycentric coordinates to locate points in 3D. Four barycentric coordinates induce a “tetrahedronal” space, rather than the “triangular” space we get when there are three coordinates.

To convert a point from barycentric coordinates to standard Cartesian coordinates, we simply compute the weighted average of the vertices by applying Equation (9.17). The opposite conversion—computing the barycentric coordinates from Cartesian coordinates—is slightly more difficult, and is discussed in Section 9.6.4. However, before we get too far into the details (which might be skipped over by a casual reader), now that you have the basic idea behind barycentric coordinates, let us take this opportunity to mention a few places where barycentric coordinates are useful.

In graphics, it is common for parameters to be edited (or computed) per vertex, such as texture coordinates, colors, surface normals, lighting values, and so forth. We often then need to determine the interpolated value of one of those parameters at an arbitrary location within the triangle. Barycentric coordinates make this task easy. We first determine the barycentric coordinates of the interior point in question, and then take the weighted average of the values at the vertices for the parameter we seek.

Another important example is intersection testing. One simple way to perform ray-triangle

testing is to determine the point where the ray intersects the infinite plane containing the

triangle, and then to decide whether this point lies within the triangle. An easy way to make

this decision is to calculate the barycentric coordinates of the point, using the techniques

described here. If all of the coordinates lie in the

9.6.4Calculating Barycentric Coordinates

Now let's see how to determine barycentric coordinates from Cartesian coordinates. We start in

2D with Figure 9.20, which shows the three vertices

We know the Cartesian coordinates of the three vertices and the point

Solving this system of equations yields

Computing barycentric coordinates for a 2D point

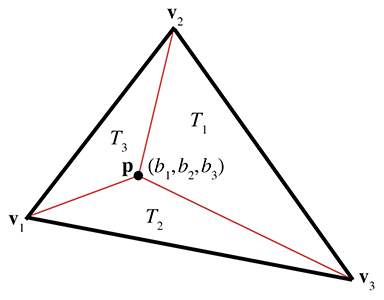

Examining Equation (9.18) closely, we see that the denominator is the same

in each expression—it is equal to twice the area of the triangle, according to

Equation (9.15). What's more, for each barycentric coordinate

Note that this interpretation applies even if

Computing barycentric coordinates for an arbitrary point

One trick that works is to turn the 3D problem into a 2D problem simply by discarding one of

But which coordinate should we discard? We can't just always discard the same one, since the

projected points will be collinear if the triangle is perpendicular to the projection plane. If

our triangle is nearly perpendicular to the plane of projection, we will have problems with

floating point accuracy. A solution to this dilemma is to choose the plane of projection so as

to maximize the area of the projected triangle. This can be done by examining the plane normal,

and whichever coordinate has the largest absolute value is the coordinate that we will discard.

For example, if the normal is

bool computeBarycentricCoords3d(

const Vector3 v[3], // vertices of the triangle

const Vector3 &p, // point that we wish to compute coords for

float b[3] // barycentric coords returned here

) {

// First, compute two clockwise edge vectors

Vector3 d1 = v[1] - v[0];

Vector3 d2 = v[2] - v[1];

// Compute surface normal using cross product. In many cases

// this step could be skipped, since we would have the surface

// normal precomputed. We do not need to normalize it, although

// if a precomputed normal was normalized, it would be OK.

Vector3 n = crossProduct(d1, d2);

// Locate dominant axis of normal, and select plane of projection

float u1, u2, u3, u4;

float v1, v2, v3, v4;

if ((fabs(n.x) >= fabs(n.y)) && (fabs(n.x) >= fabs(n.z))) {

// Discard x, project onto yz plane

u1 = v[0].y - v[2].y;

u2 = v[1].y - v[2].y;

u3 = p.y - v[0].y;

u4 = p.y - v[2].y;

v1 = v[0].z - v[2].z;

v2 = v[1].z - v[2].z;

v3 = p.z - v[0].z;

v4 = p.z - v[2].z;

} else if (fabs(n.y) >= fabs(n.z)) {

// Discard y, project onto xz plane

u1 = v[0].z - v[2].z;

u2 = v[1].z - v[2].z;

u3 = p.z - v[0].z;

u4 = p.z - v[2].z;

v1 = v[0].x - v[2].x;

v2 = v[1].x - v[2].x;

v3 = p.x - v[0].x;

v4 = p.x - v[2].x;

} else {

// Discard z, project onto xy plane

u1 = v[0].x - v[2].x;

u2 = v[1].x - v[2].x;

u3 = p.x - v[0].x;

u4 = p.x - v[2].x;

v1 = v[0].y - v[2].y;

v2 = v[1].y - v[2].y;

v3 = p.y - v[0].y;

v4 = p.y - v[2].y;

}

// Compute denominator, check for invalid

float denom = v1*u2 - v2*u1;

if (denom == 0.0f) {

// Bogus triangle - probably triangle has zero area

return false;

}

// Compute barycentric coordinates

float oneOverDenom = 1.0f / denom;

b[0] = (v4*u2 - v2*u4) * oneOverDenom;

b[1] = (v1*u3 - v3*u1) * oneOverDenom;

b[2] = 1.0f - b[0] - b[1];

// OK

return true;

}

Another technique for computing barycentric coordinates in 3D is based on the method for

computing the area of a 3D triangle using the cross product, which is discussed in

Section 9.6.2. Recall that given two edge vectors

There is one slight problem with this: the magnitude of the cross product is not sensitive to the ordering of the vertices—magnitude is by definition always positive. This will not work for points outside the triangle, since these points must always have at least one negative barycentric coordinate.

Let's see if we can find a way to work around this problem. It seems like what we really need is a way to calculate the length of the cross product vector that would yield a negative value if the vertices were enumerated in the “incorrect” order. As it turns out, there is a very simple way to do this with the dot product.

Let's assign

Dividing this result by two, we have a way to compute the “signed area” of a

triangle in 3D. Armed with this trick, we can now apply the observation from the previous

section, that each barycentric coordinate

As Figure 9.21 shows, each vertex has a vector from

We'll also need a surface normal, which can be computed by

Now the areas for the entire triangle (which we'll simply call

Each barycentric coordinate

Notice that

This technique for computing barycentric coordinates involves more scalar math operations than the method of projection into 2D. However, it is branchless and offers better SIMD optimization.

9.6.5Special Points

In this section we discuss three points on a triangle that have special geometric significance:

- center of gravity

- incenter

- circumcenter.

To present these classic calculations, we follow Goldman's article [3] from Graphics Gems. For each point, we discuss its geometric significance and construction and give its barycentric coordinates.

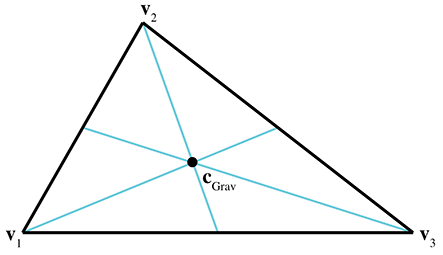

The center of gravity is the point on which the triangle would balance perfectly. It is the intersection of the medians. (A median is a line from one vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side.) Figure 9.22 shows the center of gravity of a triangle.

The center of gravity is the geometric average of the three vertices:

The barycentric coordinates are

The center of gravity is also known as the centroid.

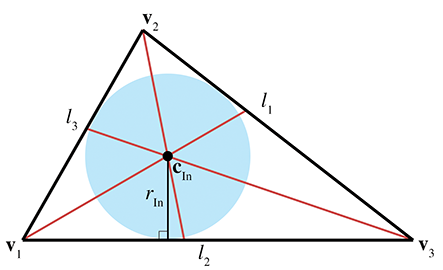

The incenter is the point in the triangle that is equidistant from the sides. It is called the incenter because it is the center of the circle inscribed in the triangle. The incenter is constructed as the intersection of the angle bisectors, as shown in Figure 9.23.

The incenter is computed by

where

The radius of the inscribed circle can be computed by dividing the area of the triangle by its perimeter:

The inscribed circle solves the problem of finding a circle tangent to three lines.

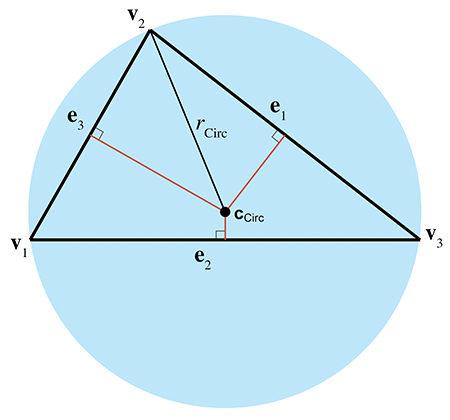

The circumcenter is the point in the triangle that is equidistant from the vertices. It is the center of the circle that circumscribes the triangle. The circumcenter is constructed as the intersection of the perpendicular bisectors of the sides. Figure 9.24 shows the circumcenter of a triangle.

To compute the circumcenter, we first define the following intermediate values:

With those intermediate values, the barycentric coordinates for the circumcenter are given by

thus, the circumcenter is given by

The circumradius is given by

The circumradius and circumcenter solve the problem of finding a circle that passes through three points.

9.7Polygons

This section introduces polygons and discusses a few of the most important issues that arise when dealing with polygons. It is difficult to come up with a simple definition for polygon, since the precise definition usually varies depending on the context. In general, a polygon is a flat object made up of vertices and edges. The next few sections will discuss several ways in which polygons may be classified.

Section 9.7.1 presents the difference between simple and complex polygons and mentions self-intersecting polygons. Section 9.7.2 discusses the difference between convex and concave polygons. Section 9.7.3 describes how any polygon may be turned into connected triangles.

9.7.1Simple versus Complex Polygons

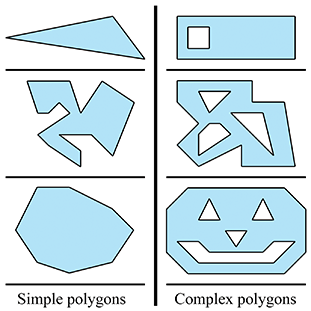

A simple polygon does not have any “holes,” whereas a complex polygon may have holes (see Figure 9.25.) A simple polygon can be described by enumerating the vertices in order around the polygon. (Recall that in a left-handed world, we usually enumerate them in clockwise order when viewed from the “front” side of the polygon.) Simple polygons are used much more frequently than complex polygons.

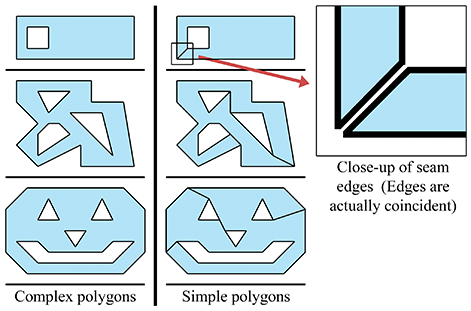

We can turn any complex polygon into a simple one by adding pairs of “seam” edges, as shown in Figure 9.26. As the close-up on the right shows, we add two edges per seam. The edges are actually coincident, although in the close-up they have been separated so you could see them. When we think about the edges being ordered around the polygon, the two seam edges point in opposite directions.

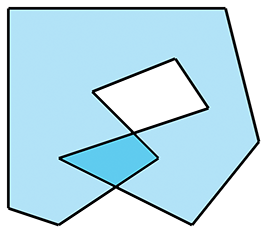

The edges of most simple polygons do not intersect each other. If the edges do intersect, the polygon is considered a self-intersecting polygon. An example of a self-intersecting polygon is shown in Figure 9.27.

Most people usually find it easier to arrange things so that self-intersecting polygons are either avoided, or simply rejected. In most situations, this is not a huge burden on the user.

9.7.2Convex versus Concave Polygons

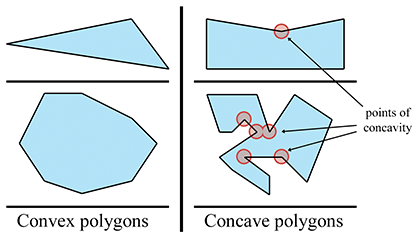

Non-self-intersecting simple polygons may be further classified as either convex or concave. Giving a precise definition for “convex” is actually somewhat tricky because there are many sticky degenerate cases. For most polygons, the following commonly used definitions are equivalent, although some degenerate polygons may be classified as convex according to one definition and concave according to another.

- Intuitively, a convex polygon doesn't have any “dents.” A concave polygon has at least one vertex that is a “dent,” which is called a point of concavity (see Figure 9.28).

- In a convex polygon, the line between any two points in the polygon is completely contained within the polygon. In a concave polygon, there is at least one pair of points in the polygon for which the line between the points is partially outside the polygon.

- As we move around the perimeter of a convex polygon, at each vertex we will turn in the same direction. In a concave polygon, we will make some left-hand turns and some right-hand turns. We will turn the opposite direction at the point(s) of concavity. (Note that this applies to non-self-intersecting polygons only.)

As we mentioned, degenerate cases can make even these relatively clear-cut definitions blurry. For example, what about a polygon with two consecutive coincident vertices, or an edge that doubles back on itself? Are those polygons considered convex? In practice, the following “definitions” for convexity are often used:

- If my code, which is supposed to work only for convex polygons, can deal with it, then it's convex. (This is the “if it ain't broke, don't fix it” definition.)

- If my algorithm that tests for convexity decides it's convex, then it's convex. (This is an “algorithm as definition” explanation.)

For now, let's ignore the pathological cases, and give some examples of polygons that we can all agree are definitely convex or definitely concave. The top concave polygon in Figure 9.28 has one point of concavity. The bottom concave polygon has five points of concavity.

Any concave polygon may be divided into convex pieces. The basic idea is to locate the points of concavity (called “reflex vertices”) andsystematically remove them by adding diagonals. O`Rourke [6] provides an algorithm that works for simple polygons, and de Berg et al. [2] show a more complicated method that works for complex polygons as well.

How can we know if a polygon is convex or concave? One method is to

examine the sum of the angles at the vertices. Consider a convex

polygon with

First, let

Second, as we will show in Section 9.7.3, any convex polygon with

Unfortunately, the sum of the interior angles is

Listing 9.7 shows how to determine if a polygon is convex by summing the angles.

bool isPolygonConvex(

int n, // Number of vertices

const Vector3 vl[], // pointer to array of of vertices

) {

// Initialize sum to 0 radians

float angleSum = 0.0f;

// Go around the polygon and sum the angle at each vertex

for (int i = 0 ; i < n ; ++i) {

// Get edge vectors. We have to be careful on

// the first and last vertices. Also, note that

// this could be optimized considerably

Vector3 e1;

if (i == 0) {

e1 = vl[n-1] - vl[i];

} else {

e1 = vl[i-1] - vl[i];

}

Vector3 e2;

if (i == n-1) {

e2 = vl[0] - vl[i];

} else {

e2 = vl[i+1] - vl[i];

}

// Normalize and compute dot product

e1.normalize();

e2.normalize();

float dot = e1 * e2;

// Compute smaller angle using ``safe'' function that protects

// against range errors which could be caused by

// numerical imprecision

float theta = safeAcos(dot);

// Sum it up

angleSum += theta;

}

// Figure out what the sum of the angles should be, assuming

// we are convex. Remember that pi rad = 180 degrees

float convexAngleSum = (float)(n - 2) * kPi;

// Now, check if the sum of the angles is less than it should be,

// then we're concave. We give a slight tolerance for

// numerical imprecision

if (angleSum < convexAngleSum - (float)n * 0.0001f) {

// We're concave

return false;

}

// We're convex, within tolerance

return true;

}

Another method for determining convexity is to search for vertices that are points of concavity. If none are found, then the polygon is convex. The basic idea is that each vertex should turn in the same direction. Any vertex that turns in the opposite direction is a point of concavity. We can determine which way a vertex turns using by the cross product on the edge vectors. Recall from Section 2.12.2 that in a left-handed coordinate system, the cross product will point towards you if the vectors form a clockwise turn. By “towards you,” we assume you are viewing the polygon from the front, as determined by the polygon normal. If this normal is not available to us initially, care must be exercised in computing it; because we do not know if the polygon is convex or not, we cannot simply choose any three vertices to compute the normal from. The techniques in Section 9.5.3 for computing the best fit normal from a set of points can be used in this case.

Once we have a normal, we check each vertex of the polygon, computing a normal at that vertex using the adjacent clockwise edge vectors. We take the dot product of the polygon normal with the normal computed at that vertex to determine if they point in opposite directions. If so (the dot product is negative), then we have located a point of concavity.

In 2D, we can simply act as if the polygon were in 3D at the plane

9.7.3Triangulation and Fanning

Any polygon can be divided into triangles. Thus, all of the operations and calculations for triangles can be piecewise applied to polygons. Triangulating complex, self-intersecting, or even simple concave polygons is no trivial task [6][2] and is slightly out of the scope of this book.

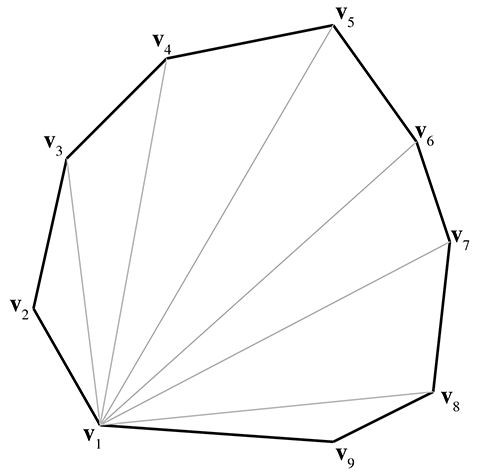

Luckily, triangulating simple convex polygons is a trivial matter. One obvious

triangulation technique is to pick one vertex (say, the first one) and “fan” the polygon around

this vertex. Given a polygon with

Fanning tends to create many long, thin sliver triangles, which can be troublesome in some situations, such as computing a surface normal. Certain consumer hardware can run into precision problems when clipping very long edges to the view frustum. Smarter techniques exist that attempt to minimize this problem. One idea is to triangulate as follows: Consider that we can divide a polygon into two pieces with a diagonal between two vertices. When this occurs, the two interior angles at the vertices of the diagonal are each divided into two new interior angles. Thus, a total of four new interior angles are created. To subdivide a polygon, select the diagonal that maximizes the smallest of these four new interior angles. Divide the polygon in two using this diagonal. Recursively apply the procedure to each half, until only triangles remain. This algorithm results in a triangulation with fewer slivers.

Exercises

-

Given the 2D ray in parametric form

determine the line that contains this ray, in slope-intercept form.

-

Give the slope and

-

Consider the set of five points:

-

(a)Determine the AABB of this box. What are

- (b)List all eight corner points.

- (c)Determine the center point

-

(d)Multiply the five points by the following matrix, which we hope you

recognize as a

- (e)What is the AABB of these transformed points?

- (f)What is the AABB we get by transforming the original AABB? (The bounding box of the transformed corner points.)

-

(a)Determine the AABB of this box. What are

-

Consider a triangle defined by

the clockwise enumeration of the vertices

- (a)What is the plane equation of the plane containing this triangle?

-

(b)Is the point

- (c)Compute the barycentric coordinates of the point

- (d)What is the center of gravity?

- (e)What is the incenter?

- (f)What is the circumcenter?

-

What is the best-fit plane equation for the following points, which are

not quite coplanar?

-

Consider a convex polygon

Outside his rectangular shack

When a triangle came down–keerplunk!–

“I must go to the hospital,”

Cried the wounded square,

So a passing rolling circle

Picked him up and took him there.