Chapter 9 discussed a number of calculations that can be performed on a single primitive. Here, we present a number of useful calculations that operate on more than one primitive. This appendix is a collection of various geometric calculations that are sometimes useful. It is also instructive to browse these tests, because many illustrate general principles.

A more comprehensive list of fast intersection methods can be found at http://www.realtimerendering.com/intersections.html.

A.1Closest Point on 2D Implicit Line

Consider an infinite line

where

Let

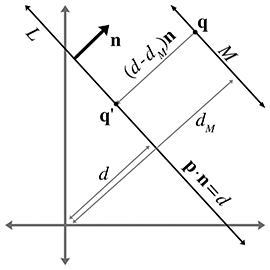

Now the signed distance from

This distance is obviously the same as the distance from

A.2Closest Point on a Parametric Ray

Consider the parametric ray

where

This is just a simple matter of projecting one vector onto another, which was presented in

Section 2.11.2. Let

The value of the dot product

Actually, Equation (A.2), for

If the ray is defined where

A.3Closest Point on a Plane

Consider a plane

where

We showed how to compute the distance from a point to a plane in

Section 9.5.4. To compute

Notice that this is the same as Equation (A.1), which computes the closest point to an implicit line in 2D.

A.4Closest Point on a Circle or Sphere

Imagine a 2D point

Let

Now, clearly,

Adding this displacement to

If

A.5Closest Point in an AABB

Let

if (x < minX) {

x = minX;

} else if (x > maxX) {

x = maxX;

}

if (y < minY) {

y = minY;

} else if (y > maxY) {

y = maxY;

}

if (z < minZ) {

z = minZ;

} else if (z > maxZ) {

z = maxZ;

}

A.6Intersection Tests

The remaining sections of this chapter present an assortment of intersection tests. These tests are designed to determine whether two geometric primitives intersect, and (in some cases) to locate the intersection. We will consider different two types of intersection tests: static and dynamic.

- A static test checks two stationary primitives and detects whether the two primitives intersect. It is a Boolean test—that is, it usually returns only true (there is an intersection) or false (there is no intersection). If the test returns more details about the intersection, this extra information usually has the purpose of describing where the intersection occurred.

-

A dynamic test checks two moving primitives and

detects if and when two primitives intersect. Usually, the movement

is expressed parametrically, and therefore the result of such a

test is not only a Boolean true/false result but also a time value

(the value of the parameter

Although each object may have its own displacement over the time interval under consideration, it will be often easier to view the problem from the point of view of one of the primitives, considering that primitive to be “still” while the other primitive does all of the “moving.” We can easily do this by combining the two displacement vectors to get a single relative displacement vector that describes how the two primitives move in relation to each other. Thus, the dynamic tests will usually involve one stationary primitive and one moving primitive.

Notice that many important tests involving rays are actually dynamic tests, since a ray can be viewed as a moving point.

A.7Intersection of Two Implicit Lines in 2D

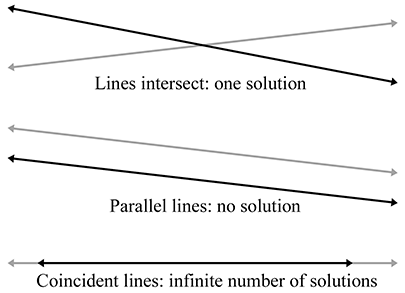

Finding the intersection of two lines defined implicitly in 2D is a straightforward matter of

solving a system of linear equations. We have two equations (the two implicit equations of the

lines) and two unknowns (the

Solving this system of equations yields

Computing the intersection of two lines in 2DJust as for any system of linear equations, there are three solution possibilities (as illustrated in Figure A.4):

- There is one solution. In this case, the denominators in Equation (A.3) will be nonzero.

- There are no solutions. This indicates that the lines are parallel and not intersecting. The denominators are zero.

- There are an infinite number of solutions. This is the case when the two lines are coincident. All the numerators and denominators are zero in this case.

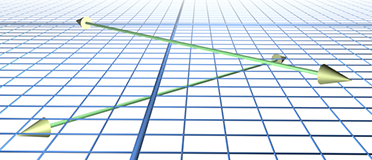

A.8Intersection of Two Rays in 3D

Given two rays in 3D defined parametrically by

we can solve for their point of intersection. For a moment, let us not restrict the range of

- The rays intersect at exactly one point.

- The rays are parallel, and there is no intersection.

- The rays are coincident, and there are an infinite number of solutions

However, in 3D we have a fourth case, where the rays are skew and do not share a common plane. An example of skew lines is illustrated in Figure A.5.

We can solve for

We obtain

If the lines are parallel (or coincident), then the cross product of

This discussion has assumed that the range of the parameters

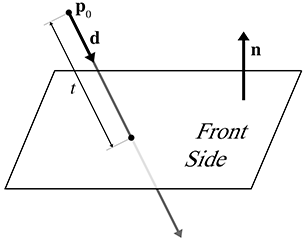

A.9Intersection of a Ray and Plane

A ray intersects a plane in 3D at a point. Let the ray be defined parametrically by

The plane will be defined in the standard implicit manner, by all points

Although we often restrict the plane normal

Let us solve for

If the ray is parallel to the plane, then the denominator

A.10Intersection of an AABB and Plane

Consider a 3D axially aligned bounding box defined by extreme points

where

One obvious implementation strategy for a static test would be to classify each corner point as

being on either the front or back side of the plane. We do this by taking the dot products of

the corner points with

As it turns out, we don't have to check all eight corner points. We'll use a trick similar to the

one used in Section 9.4.4 to transform an AABB. For example, if

// Perform static AABB-plane intersection test. Returns:

//

// <0 Box is completely on the BACK side of the plane

// >0 Box is completely on the FRONT side of the plane

// 0 Box intersects the plane

int AABB3::classifyPlane(const Vector3 &n, float d) const {

// Inspect the normal and compute the minimum and maximum

// D values.

float minD, maxD;

if (n.x > 0.0f) {

minD = n.x*min.x; maxD = n.x*max.x;

} else {

minD = n.x*max.x; maxD = n.x*min.x;

}

if (n.y > 0.0f) {

minD += n.y*min.y; maxD += n.y*max.y;

} else {

minD += n.y*max.y; maxD += n.y*min.y;

}

if (n.z > 0.0f) {

minD += n.z*min.z; maxD += n.z*max.z;

} else {

minD += n.z*max.z; maxD += n.z*min.z;

}

// Check if completely on the front side of the plane

if (minD >= d) {

return +1;

}

// Check if completely on the back side of the plane

if (maxD <= d) {

return -1;

}

// We straddle the plane

return 0;

}

A dynamic test is just one step further. Let's consider the plane to be stationary (recall from

Section A.6 that it is simpler to view the test from the frame of reference

of one of the moving objects). The displacement of the box will be defined by a unit vector

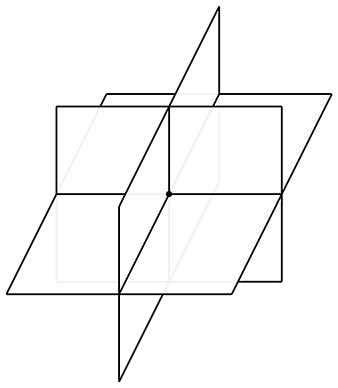

A.11Intersection of Three Planes

In 3D, three planes intersect at a point, as shown in Figure A.7.

Let the three planes be defined implicitly as

Although we usually use unit vectors for the plane normals, in this case it is not necessary that

If any pair of planes is parallel, then the point of intersection either does not exist or is not unique. In either case, the triple product in the denominator is zero.

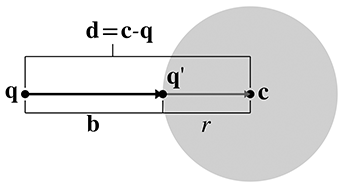

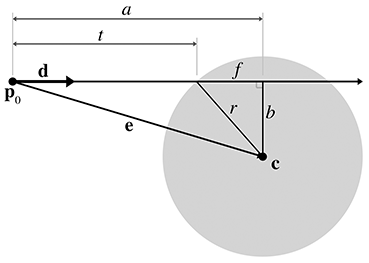

A.12Intersection of Ray and a Circle or Sphere

This section discusses how to compute the intersection of a ray and a circle in 2D. This also works for computing the intersection of a ray and a sphere in 3D, since we can operate in the plane that contains the ray and the center of the circle and turn the 3D problem into a 2D one. (If the ray lies on a line that passes through the center of the sphere, the plane is not uniquely defined. This not a problem, however, because any of the infinitely many planes that pass through the ray and the center of the sphere can be used.)

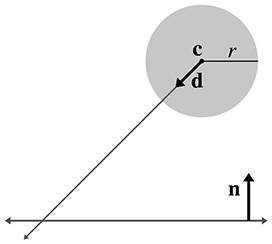

We will use a construction inspired by Hultquist [5]; see

Figure A.8. The sphere is defined by its center

In this case, we use a unit vector

We are solving for the value of

Now we project

Now all that remains is to compute

We can solve for

where

Substituting and solving for

Finally, solving for

If the argument to the square root (

The origin of the ray could be inside the sphere. This is indicated by

A.13Intersection of Two Circles or Spheres

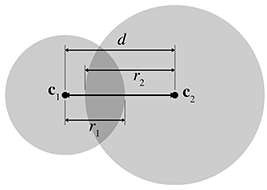

Detecting the static intersection of two spheres is relatively easy. (The discussion in this

section also applies to circles—in fact, we use circles in the diagrams.) Consider two spheres

defined by centers

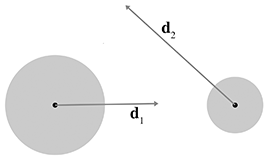

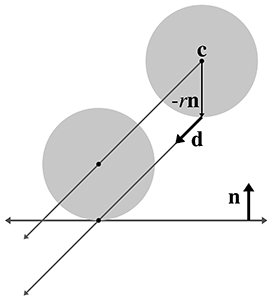

Detecting the intersection of two moving spheres is slightly more difficult. Assume, for the

moment, that we have two separate displacement vectors

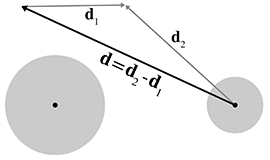

We can simplify the problem by viewing it from the point of view of the first sphere, considering

that sphere to be “stationary” while the other sphere is the “moving” sphere. This gives us

a single displacement vector

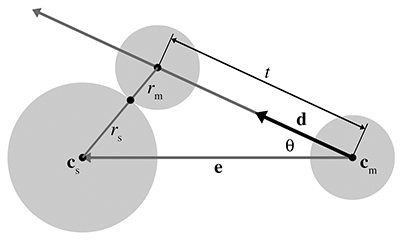

Let the stationary sphere be defined by its center

To solve for

According to the law of cosines (see Section 1.4.5), we have

Which root do we pick? The lower number (the negative root) produces the

If

A.14Intersection of a Sphere and AABB

To detect the static intersection of a sphere and an AABB, we first find the point on the box that is closest to the center of the sphere by using the techniques from Section A.5. We compute the distance from this point to the center of the sphere and compare this distance with the radius. (Actually, in practice we compare the distance squared against the radius squared to avoid the square root in the distance computation.) If the distance is smaller than the radius, then the sphere intersects the AABB.

Arvo [1] discusses this technique, which he uses for intersecting spheres with “solid” boxes. He also discusses some tricks for intersecting spheres with “hollow” boxes.

Unfortunately, the dynamic test is more complicated than the static one. For details, see Lengyel [6].

A.15Intersection of a Sphere and a Plane

Detecting the static intersection of a sphere and a plane is relatively easy—we simply compute the distance from the center of the sphere to the plane by using Equation (9.14). If this distance is less than the radius of the sphere, then the sphere intersects the plane. We can actually make a more robust test, which classifies the sphere as being completely on the front, completely on the back, or straddling the sphere. A code snippet is given in Listing A.3.

// Given a sphere and plane, determine which side of the plane

// the sphere is on.

//

// Return values:

//

// < 0 Sphere is completely on the back

// > 0 Sphere is completely on the front

// 0 Sphere straddles plane

int classifySpherePlane(

const Vector3 &planeNormal, // must be normalized

float planeD, // p * planeNormal = planeD

const Vector3 &sphereCenter, // center of sphere

float sphereRadius // radius of sphere

) {

// Compute distance from center of sphere to the plane

float d = planeNormal * sphereCenter - planeD;

// Completely on the front side?

if (d >= sphereRadius) {

return +1;

}

// Completely on the back side?

if (d <= -sphereRadius) {

return -1;

}

// Sphere intersects the plane

return 0;

}

The dynamic situation is only slightly more complicated. We consider the plane to be stationary, assigning all relative displacement to the sphere.

We define the plane in the usual manner by a normalized surface normal

The problem is greatly simplified by realizing that no matter where on the surface of the plane

the intersection occurs, the point of contact on the surface of the sphere is always the same.

That point of contact

Now that we know which point on the sphere first contacts the plane, we can use a simple

ray-plane intersection test from Section A.9. We start with our solution

to the ray-plane intersection test from Equation (A.4) and then substitute

A.16Intersection of a Ray and a Triangle

The ray-triangle intersection test is very important in graphics and computational geometry. In the absence of a special raytrace test against a given complex object, we can always represent (or at least approximate) the surface of an object as a triangle mesh and then raytrace against this triangle mesh representation.

Here we use a simple strategy from Badouel [2]. The first step is to compute the point where the ray intersects the plane containing the triangle. Section A.9 showed how to compute the intersection of a plane and a ray. Then we test to see whether that point is inside the triangle by computing the barycentric coordinates of the point, as discussed in Section 9.6.4.

To speed up this test, we use a few tricks:

- Detect and return a negative result (no collision) as soon as possible. This is known as “early out.”

- Defer expensive mathematical operations, such as division, as long as possible. This is done for two reasons. First, if the result of the expensive calculation is not needed (for example, if we took an early out), then the time we spent performing the operation was wasted. Second, it gives the compiler plenty of room to take advantage of the operator pipeline in modern processors. If an operation such as division has a long latency, then the compiler may be able to look ahead and generate code that begins the division operation early. It then generates code that performs other tests (possibly taking an early out) while the division operation is under way. Then, at execution time, if and when the result of the division is actually needed, the result will be available or at least partially completed.

- Only detect collisions where the ray approaches the triangle from the front side. This allows us to take a very early out on approximately half of the triangles. Intersecting with both sides is slightly slower.

Listing A.4 implements these techniques. Although it is commented in the listing, we have chosen to perform some floating point comparisons “backwards” since this behaves better in the presence of invalid floating point input data and NaNs (Not a Number).

float rayTriangleIntersect(

const Vector3 &rayOrg, // origin of the ray

const Vector3 &rayDelta, // ray length and direction

const Vector3 &p0, // triangle vertices

const Vector3 &p1, // .

const Vector3 &p2, // .

float minT // closest intersection found so far.

// (Start with 1.0)

) {

// We'll return this huge number of no intersection is detected

const float kNoIntersection = FLT_MAX;

// Compute clockwise edge vectors.

Vector3 e1 = p1 - p0;

Vector3 e2 = p2 - p1;

// Compute surface normal. (Unnormalized)

Vector3 n = crossProduct(e1, e2);

// Compute gradient, which tells us how steep of an angle

// we are approaching the *front* side of the triangle

float dot = n * rayDelta;

// Check for a ray that is parallel to the triangle, or not

// pointing towards the front face of the triangle.

//

// Note that this also will reject degenerate triangles and

// rays as well. We code this in a very particular

// way so that NANs will bail here. (I.e. this does NOT

// behave the same as ``dot >= 0.0f'' when NANs are involved)

if (!(dot < 0.0f)) {

return kNoIntersection;

}

// Compute d value for the plane equation. We will

// use the plane equation with d on the right side:

// Ax + By + Cz = d

float d = n * p0;

// Compute parametric point of intersection with the plane

// containing the triangle, checking at the earliest

// possible stages for trivial rejection

float t = d - n * rayOrg;

// Is ray origin on the backside of the polygon? Again,

// we phrase the check so that NANs will bail

if (!(t <= 0.0f)) {

return kNoIntersection;

}

// Closer intersection already found? (Or does

// ray not reach the plane?)

//

// since dot < 0:

//

// t/dot > minT

//

// is the same as

//

// t < dot*minT

//

// (And then we invert it for NAN checking...)

if (!(t >= dot*minT)) {

return kNoIntersection;

}

// OK, ray intersects the plane. Compute actual parametric

// point of intersection

t /= dot;

assert(t >= 0.0f);

assert(t <= minT);

// Compute 3D point of intersection

Vector3 p = rayOrg + rayDelta*t;

// Find dominant axis to select which plane

// to project onto, and compute u's and v's

float u0, u1, u2;

float v0, v1, v2;

if (fabs(n.x) > fabs(n.y)) {

if (fabs(n.x) > fabs(n.z)) {

u0 = p.y - p0.y;

u1 = p1.y - p0.y;

u2 = p2.y - p0.y;

v0 = p.z - p0.z;

v1 = p1.z - p0.z;

v2 = p2.z - p0.z;

} else {

u0 = p.x - p0.x;

u1 = p1.x - p0.x;

u2 = p2.x - p0.x;

v0 = p.y - p0.y;

v1 = p1.y - p0.y;

v2 = p2.y - p0.y;

}

} else {

if (fabs(n.y) > fabs(n.z)) {

u0 = p.x - p0.x;

u1 = p1.x - p0.x;

u2 = p2.x - p0.x;

v0 = p.z - p0.z;

v1 = p1.z - p0.z;

v2 = p2.z - p0.z;

} else {

u0 = p.x - p0.x;

u1 = p1.x - p0.x;

u2 = p2.x - p0.x;

v0 = p.y - p0.y;

v1 = p1.y - p0.y;

v2 = p2.y - p0.y;

}

}

// Compute denominator, check for invalid

float temp = u1 * v2 - v1 * u2;

if (!(temp != 0.0f)) {

return kNoIntersection;

}

temp = 1.0f / temp;

// Compute barycentric coords, checking for out-of-range

// at each step

float alpha = (u0 * v2 - v0 * u2) * temp;

if (!(alpha >= 0.0f)) {

return kNoIntersection;

}

float beta = (u1 * v0 - v1 * u0) * temp;

if (!(beta >= 0.0f)) {

return kNoIntersection;

}

float gamma = 1.0f - alpha - beta;

if (!(gamma >= 0.0f)) {

return kNoIntersection;

}

// Return parametric point of intersection

return t;

}

There is one more significant strategy, not illustrated in Listing A.4, for optimizing expensive calculations: precompute their results. If values such as the polygon normal can be computed ahead of time, then different strategies may be used.

Because of the fundamental importance of this test, programmers are always looking for ways to make it faster. The technique we have given here is a standard one that is easy to understand and produces the barycentric coordinates, often a useful byproduct, as a side effect. It is not the fastest. See Tomas Akenine-Möller's collection of intersection tests on the web page for Real-Time Rendering at http://www.realtimerendering.com/intersections.html.

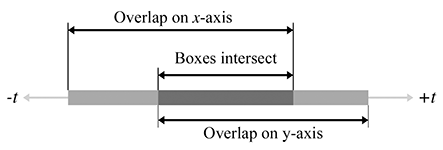

A.17Intersection of Two AABBs

Detecting the static intersection of two AABBs is an extremely important operation. Luckily, it's rather trivial.1 We simply check for overlapping extents on each dimension independently. If there is no overlap on a particular dimension, then the two AABBs do not intersect. This technique is used in Listing A.5.

bool aabbsOverlap(const AABB3 &a, const AABB3 &b) {

// Check for a separating axis.

if (a.min.x >= b.max.x) return false;

if (a.max.x <= b.min.x) return false;

if (a.min.y >= b.max.y) return false;

if (a.max.y <= b.min.y) return false;

if (a.min.z >= b.max.z) return false;

if (a.max.z <= b.min.z) return false;

// Overlap on all three axes, so their

// intersection must be non-empty

return true;

}

This strategy is actually an instance of a more general strategy known as the separating axis test. If two convex polyhedra do not overlap, then there exists a separating axis upon which, if we project the two polyhedra, their projections will not overlap. (In 3D, it's easier to visualize a plane perpendicular to the separating axis that can be placed between the two polyhedra.) The key to the separating axis method is that only a finite number of axes need to be tested: the normals of the faces and certain cross products; for details, see Ericson [3]. If the projections of the polyhedra onto those axes overlap in all cases, then it is safe to assume that no separating axis can be found. In the case of two AABBs, only the three cardinal axes need to be tested. Furthermore, these “projections” simply extract the appropriate coordinate.

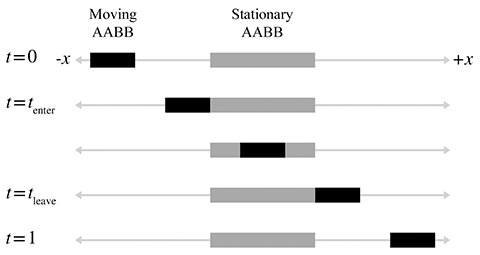

The dynamic intersection of AABBs is only slightly more complicated. Consider a stationary AABB

defined by extreme points

Our task is to compute

The problem is now one-dimensional. We need to know the interval of time when the two boxes

overlap on a particular dimension. Imagine projecting the problem onto the

As we advance in time, the line segment representing the moving box will slide along the number

line. In the illustration in Figure A.15, at

where

Likewise, we can solve for

Three important points are noted here:

-

If the denominator

-

If the moving box begins on the right side of the stationary box

and moves left, then

-

The values for

We now have a way to find the interval of time, bounded by

If the interval is empty, then the boxes never collide. If the interval lies completely outside

the range

Unfortunately, in practice, bounding boxes for objects are rarely axially aligned in the same coordinate space. However, because this test is relatively fast, it is useful as a preliminary trivial rejection test, to be followed by a more specific (and usually more expensive) test.

A.18Intersection of a Ray and an AABB

Computing the intersection of a ray with an AABB is an important calculation because the result of this test is commonly used for trivial rejection on more complicated objects. (For example, if we wish to raytrace against multiple triangle meshes, we can first raytrace against the AABBs of the meshes to trivially reject entire meshes at once, rather than having to check each triangle.)

Woo [7] describes a method that first determines which side of the box would be intersected and then performs a ray-plane intersection test against the plane containing that side. If the point of intersection with the plane is within the box, then there is an intersection; otherwise, there is no intersection. This is implemented in Listing A.6.

// Return parametric point of intersection 0...1, or a really huge

// number if no intersection is found

float AABB3::rayIntersect(

const Vector3 &rayOrg, // orgin of the ray

const Vector3 &rayDelta, // length and direction of the ray

Vector3 *returnNormal // optionally, the normal is returned

) const {

// We'll return this huge number if no intersection

const float kNoIntersection = FLT_MAX;

// Check for point inside box, trivial reject, and

// determine parametric distance to each front face

bool inside = true;

float xt, xn;

if (rayOrg.x < min.x) {

xt = min.x - rayOrg.x;

if (xt > rayDelta.x) return kNoIntersection;

xt /= rayDelta.x;

inside = false;

xn = -1.0f;

} else if (rayOrg.x > max.x) {

xt = max.x - rayOrg.x;

if (xt < rayDelta.x) return kNoIntersection;

xt /= rayDelta.x;

inside = false;

xn = 1.0f;

} else {

xt = -1.0f;

}

float yt, yn;

if (rayOrg.y < min.y) {

yt = min.y - rayOrg.y;

if (yt > rayDelta.y) return kNoIntersection;

yt /= rayDelta.y;

inside = false;

yn = -1.0f;

} else if (rayOrg.y > max.y) {

yt = max.y - rayOrg.y;

if (yt < rayDelta.y) return kNoIntersection;

yt /= rayDelta.y;

inside = false;

yn = 1.0f;

} else {

yt = -1.0f;

}

float zt, zn;

if (rayOrg.z < min.z) {

zt = min.z - rayOrg.z;

if (zt > rayDelta.z) return kNoIntersection;

zt /= rayDelta.z;

inside = false;

zn = -1.0f;

} else if (rayOrg.z > max.z) {

zt = max.z - rayOrg.z;

if (zt < rayDelta.z) return kNoIntersection;

zt /= rayDelta.z;

inside = false;

zn = 1.0f;

} else {

zt = -1.0f;

}

// Ray origin inside box?

if (inside) {

if (returnNormal != NULL) {

*returnNormal = -rayDelta;

returnNormal->normalize();

}

return 0.0f;

}

// Select farthest plane - this is

// the plane of intersection.

int which = 0;

float t = xt;

if (yt > t) {

which = 1;

t = yt;

}

if (zt > t) {

which = 2;

t = zt;

}

switch (which) {

case 0: // intersect with yz plane

{

float y = rayOrg.y + rayDelta.y*t;

if (y < min.y || y > max.y) return kNoIntersection;

float z = rayOrg.z + rayDelta.z*t;

if (z < min.z || z > max.z) return kNoIntersection;

if (returnNormal != NULL) {

returnNormal->x = xn;

returnNormal->y = 0.0f;

returnNormal->z = 0.0f;

}

} break;

case 1: // intersect with xz plane

{

float x = rayOrg.x + rayDelta.x*t;

if (x < min.x || x > max.x) return kNoIntersection;

float z = rayOrg.z + rayDelta.z*t;

if (z < min.z || z > max.z) return kNoIntersection;

if (returnNormal != NULL) {

returnNormal->x = 0.0f;

returnNormal->y = yn;

returnNormal->z = 0.0f;

}

} break;

case 2: // intersect with xy plane

{

float x = rayOrg.x + rayDelta.x*t;

if (x < min.x || x > max.x) return kNoIntersection;

float y = rayOrg.y + rayDelta.y*t;

if (y < min.y || y > max.y) return kNoIntersection;

if (returnNormal != NULL) {

returnNormal->x = 0.0f;

returnNormal->y = 0.0f;

returnNormal->z = zn;

}

} break;

}

// Return parametric point of intersection

return t;

}

- This is one of Fletcher's favorite interview questions. It's surprising how many programmers do not know how to perform this very simple operation. Don't be one of those applicants!