It's an energy field created by all living things.

It surrounds us and penetrates us.

It binds the galaxy together.

Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1977)

Chapter 11 was about linear kinematics—how to describe the motion of object, without concerning ourselves with the “cause” of the motion, its orientation, or how we might go about simulating that object on a computer. The main goals of this chapter are to address those three topics.

- Section 12.1 identifies and quantifies the “cause” of motion, force, and presents three physical laws formalized more than 400 years ago by Isaac Newton in his masterwork the Principia.

- Section 12.2 discusses a few particularly important and simple types of forces.

- Section 12.3 introduces momentum and presents the important relationship between force and momentum.

- Section 12.4 is about collisions and impulses, which are large forces that act for short durations.

- Section 12.5 considers the rotation of objects and the angular analogs of the linear concepts introduced up to this point.

- Section 12.6 turns to matters of implementation, looking at some basic problems that a digital simulation needs to address. It gives an overview of how contemporary real-time rigid body simulations solve them.

12.1Newton's Three Laws

Sir Isaac Newton established three simple laws that provide a framework, commonly known as Newtonian mechanics, for understanding such diverse physical systems as an apple falling from a tree, the motion of the planets, and the physical interactions that happen in a video game. Newtonian mechanics is also called classical mechanics, and that name should alert you to the fact that the laws we are about to study are wrong, in the sense that they do not agree with the result of experiments conducted at very high speed (which require relativistic mechanics) or at very small scale (which require quantum mechanics).1 For everyday phenomena (and for the phenomena we need to simulate in a video game), the discrepancy between the results predicted by Newtonian mechanics and the correct results (as correctly predicted by quantum-relativistic mechanics) is generally less than can be detected with the most accurate instruments. The differences in the predictions become significant only at speeds very close to the speed of light and at scales approaching the size of an atom; otherwise, all the theories are in great agreement with each other and with experimental results. It was precisely because Newtonian mechanics has such a long and decorated history of accurate predictions that it was so shocking to find out that the laws were in need of correction. It should be clear that these laws, having been sufficient to describe the motions of the heavenly bodies to a great deal of accuracy, will also be quite sufficient for our purposes here.

12.1.1Newton's First Two Laws: Force and Mass

Chapter 11 noted that mass measures the degree to which an object resists being accelerated. This resistance is called inertia, and the physical quantity needed to overcome it and create an acceleration is called force. In other words, all of those “causes of motion” that we so scrupulously avoided mentioning in the previous chapter actually go by the collective name force.

The idea that objects resist acceleration is summarized by Newton's first law.

This seems like quite a simple statement, even in the anachronistic translation of Newton's original Latin. But consider how audacious it was for Newton to assert this, when it so clearly is at odds with the commonsense observations we all have from our daily lives! A more “commonsense” way to think about force is to assume that force is needed not only to start an object in motion, but also to maintain its motion. (This is the rule under so-called Aristotelian dynamics.) After all, once we stop applying the force, eventually the object will stop moving, right? According to Newton, once an object is set in motion, it does not require any force to continue this motion. In fact, Newton claims that the force is required to stop the object, and absent this stopping force, the object will continue on indefinitely.

Of course, the reason Newton's first law seems counterintuitive is that in our everyday experience, when we set objects in motion, they are always brought to a stop by the ubiquitous force of friction. But we can argue that Newton's law is correct, even though objects always come to a stop through friction, with a simple thought experiment. Imagine we apply a certain amount of force and set an object in motion across a surface. The object will travel a certain distance and eventually come to a stop. Did it stop due the lack of continued pushing force, or due to some force that acted to slow it down? If we perform the same experiment on different surfaces, performing the initial push in the same manner in each case, we find that the object travels farther on a smoother surface, and less distance on a rougher surface. You probably aren't surprised at these ”commonsense” results, but notice how they actually contradict the notion that a force is required to keep the object in motion and validate Newton's laws.

Newton clarified the precise relationship among mass, acceleration, and net force in his second law.

This simple equation is the most important one in this chapter. You should certainly memorize

it. It basically says that whenever a particle with mass

Now this does not mean that when there are any forces on an object, it will necessarily

accelerate. Nor does it mean that if an object is not accelerating, then there are no forces

acting on it. The

What sort of quantity is force? First of all, force has magnitude and direction, and so it is a

vector quantity, just like acceleration (although at times it is easier to study force in a

one-dimensional setting, just like we did with acceleration). And force must have the same

dimensions (1D, 2D, or 3D, depending on the “world” in which we are working) as the

acceleration

Let's use dimensional analysis to determine the physical units that we should use to measure

force. Mass is one of our fundamental quantities, denoted

When measuring with the SI units—mass in kilograms, length in meters, and time in seconds—force has the units of “kilogram meter per second squared.” This is quite a mouthful, so it goes by a special name, the Newton, denoted N:

The Newton is an SI unit of force

If you're having trouble grasping just what a “kilogram meter per second squared” is, just

remember that a Newton is the amount of force required to accelerate a mass of 1 kg at a rate of

1 m/

There's a common misunderstanding that we'd like to cut off as early as possible. Force creates an acceleration on a body, and it acts over time. For example, the question, “How much force does it take to get a 100 lb object to go 100 mi/hr?” does not make sense. Force doesn't produce velocity directly, it causes the velocity to change over time. This can be especially confusing when you consider collisions, such as a ball bouncing on the floor or being struck by a bat. Although the velocity appears to have changed instantaneously, what is really happening is that a very large force is acting for a very short (but finite) duration. We study collisions in more detail in Section 12.3. Typically in digital simulations impulsive forces are handled differently from more persistent forces that act over several simulation steps, so for now, don't think of a force as an impact; instead, think of it as more of a gradual push or pull that could be provided by, for example, a spring, the wind, or gravity.

We said that Equation (12.1) is the traditional way to express the relationship among force, mass, and acceleration. However, written in that way, with force on the left-hand side, you might get the idea that the common situation is for us to know the mass and acceleration, and use Newton's laws to compute the force. In fact, especially in digital simulations, the more common scenario is that we have calculated the forces acting on a body, and we wish to predict the body's response to those forces. In other words, we'll usually use Newton's second law in the form

We usually use this form of Newton's second lawMost physics textbooks teach the important conceptual tool known as a free-body diagram. Newton's second law, especially as expressed in Equation (12.2), is at the heart of this exercise. The basic procedure is as follows, starting with a representation of the object.

- Draw and label all the forces acting on it.

- Sum up those forces (using vector addition) to compute the net force.

- Use Newton's second law (Equation (12.2)) to compute the acceleration of the object.

- Integrate the acceleration to determine the motion of the object. When solving problems analytically, this means solving differential equations. We don't use any differential equations in this book because there are only a few simple cases that we will look at analytically. Numerical methods of integration must be used. Later, we examine Euler integration, which is the most simple method imaginable, but also the one used by most real-time rigid body simulators.

The above procedure is a very important tool that we use several times in Section 12.2; it's also essentially how most digital physics simulations work inside a computer. Of course, the simplicity with which we've described this 4-step process hides many troublesome difficulties. The forces in Equation (12.2) may vary continuously over time; be dependent on time, position, and velocity; exhibit nonlinearities or discontinuities; and in general be difficult to compute exactly or express and integrate in closed form. Section 12.6 deals with physics simulations, but for now the key point that we want to emphasize is that Newton's second law is the fundamental driving equation.

12.1.2Inertial Reference Frames

If we take the special case where

The vectors

For example, imagine a robot eating a herring sandwich in an elevator. Someone cuts the elevator

cables, and the elevator, robot, and sandwich begin to fall. Now, this robot has been programmed

with the knowledge that it likes to eat herring sandwiches,2 but without any

general sense of self-preservation, so it does not panic. It looks at the herring sandwich

floating in mid-air instead of falling to the elevator floor, as it would reasonably expect. The

robot, having also been programmed with an incomplete understanding of Newton's laws, thinks to

itself, “My goodness, this is quite unusual! I know gravity must be pulling this sandwich

downwards and I know

A viewer on the ground would not see any need to invent a fictitious force to explain the

sandwich's behavior. Using a reference frame with the origin fixed at the bottom of the

building, the viewer sees the sandwich as accelerating downward, and has no reason to think

anything is amiss.3

The person driving by in a car also doesn't see any problems. In the reference frame of the car,

the sandwich appears to travel in a

parabolic motion. But the relation

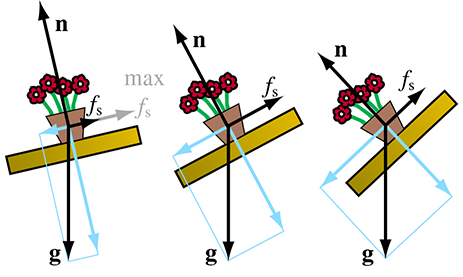

In summary, if a reference frame is accelerating or rotating, the motion of objects described using that reference frame will not be consistent with mechanical laws. An inertial reference frame must be stationary or moving at a constant linear velocity.

12.1.3Newton's Third Law

Newton's third law is often misunderstood in spite of being the one most often quoted. It has a certain zen-like justice to it.5

This law basically says that there is no such thing as a single unilateral force. If object

In diagrams, we often draw a force as an arrow, since it is a vector. But really, these diagrams would be more accurate if both ends of the arrow had arrowheads. When we leave off the other side of the arrow, it's because it is acting on an object in which we have no interest. When you see a single-sided arrow that represents a force in a diagram, you can always fill in the other half in your mind.

One source of misunderstanding of Newton's third law is the word “reaction.” The purpose of this word is to describe the forces as being in opposition to one another. It is not meant to imply a causal link between them; neither force is a “cause” or “effect.” The two opposing forces act simultaneously and, so far as the laws of physics are concerned, have equal status.

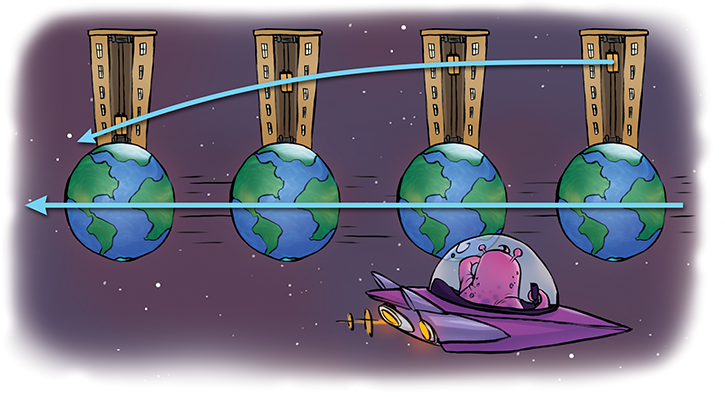

But aside from this mistaken inference of cause and effect, the third law is just plain counterintuitive. Let's say a guy named Moe pushes a box forward on the ground. The box weighs twice as much as Moe, and he has placed it on a cart that rolls with very little friction. According to Newton's third law, the box pushes back on Moe. But then why does the box accelerate and Moe doesn't? It doesn't look like there are “equal and opposite actions” happening here.

Conundrums such as these are always resolved by considering all the forces acting on both bodies. In the example just discussed, Moe is not floating in midair, or else he would have been accelerated backwards just as Newton's third law predicts he would. (Consider what would happen if Moe and the box were on ice.) No, Moe is standing on the ground. Through the force of friction, Moe pushes against the Earth and the Earth pushes back on Moe. In fact, if we assume that Moe makes some forward progress instead of just being stuck there grunting, then the force of the Earth pushing against him must exceed the force of the box pushing back against him, and he accelerates forward. This is illustrated in Figure 12.3.

An inquisitive reader might wonder about the previous scenario, “Why doesn't the Earth then accelerate?” The short answer is, “It does!” A medium-length answer is, “It does, in the short run.” For the full length answer, we have to wait until Section 12.3, which tells us a little bit about momentum.

Of course, these theoretical questions are certainly interesting to ponder, but what practical application is there for Newton's third law? The most important application, for our purposes, is the justification to simplify a rigid body and treat it as a single particle. For example, earlier we considered the forces acting on a large beam in a skyscraper. What if the beam is not a single solid piece, but instead it is really two beams that have been bolted together? Then really what is happening is that forces push down on the top part of the beam, which pushes down on the bottom part of the beam, which pushes down on the Earth. Likewise, the Earth is pushing back up on the bottom part of the beam, which pushes up on the top part of the beam.

But why stop there? Isn't any object actually composed of not just two or three pieces, but trillions of molecules? How can we possibly calculate all these complicated quantum-electrical forces? This is where Newton's third law comes in. We are justified in the treatment of this spliced beam as a single rigid body, and we can ignore all the internal forces, provided that the body stays rigid, which means that all pairs of points within the object maintain a fixed distance from each other. In this situation, the parts are not accelerating relative to each other, and this means that the internal forces must be exactly balanced. In other words, all the internal forces cancel each other out and thus make no contribution to the net force, which is why we can ignore them. Of course, to the extent that the pieces do accelerate relative to each other, any calculations we make ignoring the internal forces will be inaccurate. If the bending or compression of the object is very slight, then our calculations will not be perfect, but they will be very close; if the object breaks apart, then our calculations will be meaningless.

We can generalize arguments such as this even further to the case where the parts are moving relative to each other. Of course, an object with moving internal parts is the opposite of a rigid body; however, we'll see that in many respects we are still able treat these complicated systems as “particles.” Section 12.3 discusses this idea and how it allows us to resolve the conundrum of Moe and his box.

12.2Some Simple Force Laws

Many different types of forces are at work in our universe.6 In a real-time

simulation, we often ignore certain forces, make approximations to them, and even invent

fictional7 forces to achieve a desired effect (such as forcing

a trajectory to obey an animator's constraints, or helping the AI or the player hit the target).

Although our guiding principle is always

This section discusses three important forces that exist in the real world and are often used in physics simulations. Gravity, friction, and springs are the subjects of Section 12.2.1, Section 12.2.2, and Section 12.2.3, respectively. Of course, a computer simulation may need to consider many more real-world forces, such as buoyancy, drag, or lift. The goal of this book is to give an overview of the most important topics and not to be exhaustive; however, sources that cover these types of forces are listed in the suggested reading in Section 12.7.

One other extremely important force that appears in physics simulations is the contact force, also known as a normal force. This is the force that prevents objects from penetrating each other. When a box is resting on a table, the force the table exerts on the box, counteracting the force of gravity and preventing the box from accelerating downwards, is called a contact force. Contact forces in a physics engine are inherently tied up with the engine's method for resolving collisions and are usually handled in a way that forms a compromise between the stability of the simulation and physical reality. As such, the details for how contact forces are computed can vary from one physics engine to another; indeed, resolving collisions is a very active area of research.

12.2.1Gravitational Force

In Principia, Newton stated all sorts of laws in addition to the three for which he is the most famous. One such law, which he discovered through analysis of the motions of the planets, is the law of universal gravitation, which states that all objects in the universe feel an attractive force to each other. This force is proportionate to the product of their masses and inversely proportionate to the square of the distance between the objects and can be calculated by Equation (12.3).

In this equation,

The law of universal gravitational attraction is very helpful if you want to understand planetary

motion or the tides, or just need a cheesy

pick-up line.8 However, most simulations are confined to a fairly small region close to Earth's surface.

When we make the typical assumption that one Cartesian axis points “down,” we are ignoring the

curvature of Earth and also locking in the direction of the force of

gravity to a constant. It's also common to ignore the slight decrease in the strength of gravity

that occurs at higher altitudes, and assume a constant value for

In Equation (12.4),

Chapter 11 told you what the magnitude of

But wait, this value is larger than the value of 9.81 quoted earlier! The reason for the

difference is that, while Earth's gravity provides a

centripetal force, its rotation creates an apparent

centrifugal force, which partly counteracts gravity. We calculated the magnitude of the

acceleration required to keep objects from spinning out into space in

Section 11.8. At the equator, Earth's rotation

requires that gravity provide a centripetal acceleration of

Subtracting this apparent centrifugal force from the force of gravity gives us

Now that we've discussed at some length the strength of gravity in the real world, let's talk about how this number is often completely irrelevant in video games. In certain genres, such as racing or flight simulators, realism is important. However, in most other video games, the first law of video game physics applies. (Hey, Newton made up some laws, so why can't we?)

For example, first-person shooters are notorious for poor jumping mechanics. The most important reason is probably the fundamental fact that you cannot see your feet, yet some first-person games have for some reason added jumping puzzles. But even many third-person shooters that adopt an over-the-shoulder camera also have jumping mechanics that just don't feel right. Why? In most first-person shooters, when you jump, you are given an initial burst of upward velocity, and then your position is simulated just like every other airborne object in the world, using gravity, which causes your motion to be parabolic. Compare this to the jump mechanic in most third-person action games. Most of these games do not simulate jumps using a constant acceleration. Instead, your character will spring up almost instantaneously after you hit the button, and reach a maximum height very quickly. In many games, the character will hover at that maximum height for a duration, and then slam back down on the ground as quickly as it rose up, perhaps leaving a crater behind. This is clearly not physically accurate, but then again, neither is being able to jump two or three times your own height, steer in midair, or double jump. When it comes to jumping in video games, reality is not just overrated, it's completely ignored. It just doesn't feel right.

If simulating a jump mechanic using gravity makes for a bad jump mechanic, simulating a jump

mechanic using a value of

There are also reasons to fiddle with gravity for non-player-character objects as well. Sometimes real-world gravity can create an “objects made of styrofoam” feeling for simulated objects in general,9 so gravity is increased to get an object to tip over and come to rest more quickly. In other situations, an artificially low value of gravity can make a large object seem even more massive (especially when accompanied by the right sound effects), because acceleration on Earth is constant and is one of a few cues humans instinctively use to establish an absolute scale for objects in the distance.10

Hopefully, while reading the preceding design discussion you absorbed a general message rather than focusing on our specific opinions. What “feels right” is a subjective matter; furthermore—and this is the key point—it is based more on player expectation than physical reality. In the end, what matters most in a video game is not what's going on in the CPU or even on the screen, but what is going on in the player's mind. And the human mind is highly susceptible to suggestion. When creating video games, always remember that the quest for realism should never be an end unto itself, but rather a successful video game will harness realism only where it serves the ultimate goal, which is entertainment. In fact, realism is quite often opposed to this goal. Video game makers (especially programmers!) often get these priorities confused and end up creating an impressive technical demo that isn't any fun.

12.2.2Frictional Forces

If we take an object such as a bowl of petunias and slide it along a surface, we know that it will eventually come to a stop. We also know that if we place this bowl on a surface that isn't quite level, it won't necessarily slide downhill unless the angle of inclination exceeds a certain threshold. These two phenomena are slightly different aspects of the force of friction. We are accustomed to thinking of friction as an onerous enemy of productivity, the evil cause of wear on machines and more frequent trips to the gas station. But keep in mind that without friction, we wouldn't be able to walk across a room or pick up a child (or a bowl of petunias). Without friction, our cars might have better fuel efficiency, but the transmission wouldn't work and the tires would spin in place instead of propelling the car forward.

Here we consider the two modes of the standard dry friction model, which is sometimes called Coulomb friction. Although several thinkers contributed to our understanding of friction, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (1736–1806) is the guy who got his name to stick. When an object is at rest on top of another object, a certain amount of force is required to get it unstuck and set it in motion. If any less force is applied to the object, the force of friction will push back with a counteracting force up to some maximum amount. This type of friction is known as static friction, and it prevents bowls of petunias sitting on slightly inclined tables from sliding off. Once static friction is overcome and the object is moving, friction continues to push against the relative motion of the two surfaces, but the magnitude of this force, known as kinetic friction, is less than that of static friction. Kinetic friction is what causes a bowl of petunias to eventually come to a stop after we set it in motion.

Friction is the result of complicated interactions at the microscopic level, and so it is somewhat surprising that its macroscopic behavior can be described by relatively simple equations. Let's consider static friction first. Like any force, static friction is a vector. The direction of static friction is always in the direction that opposes any forces that would otherwise cause objects to move relative to each other. This might seems a bit like cheating (“How does the friction always know the correct direction to push?”), but remember that the force is actually the aggregate result of many electrical forces acting at the microscopic level. The forces are the result of molecular bonds that have formed between the objects as they came in contact, and these bonds need a force to pull them apart.

A good approximation for the maximum magnitude of static friction is computed with Equation (12.5).

The dimensionless constant

From our perspective,

| Material 1 | Material 2 | ||

| Aluminum | Steel | 0.61 | 0.47 |

| Copper | Steel | 0.53 | 0.36 |

| Leather | Metal | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Rubber | Asphalt (dry) | 0.9 | 0.5–0.8 |

| Rubber | Asphalt (wet) | 0.25–0.75 | |

| Rubber | Concrete (dry) | 1.0 | 0.6–0.85 |

| Rubber | Concrete (wet) | 0.30 | 0.45–0.75 |

| Steel | Steel | 0.80 | |

| Steel | Teflon | 0.04 | |

| Teflon | Teflon | 0.04 | |

| Wood | Concrete | 0.62 | |

| Wood | Clean metal | 0.2–0.6 | |

| Wood | Ice | 0.05 | |

| Wood | Wood | 0.25–0.5 | |

| Wood (waxed) | Dry snow | 0.04 |

Of course, somebody actually has to fill out these tables! The methods for obtaining these data are interesting and rather elegant but they are not our primary concern here. What is very important for us is that the coefficients of static and kinetic friction depend on the properties of both interacting surfaces. In other words, Table 12.1 is indexed not by a single surface type, but by a pair of interacting surfaces. So, for example, although using this table we can find the coefficient of static friction for rubber against asphalt, we cannot use this information to say anything about, for example, rubber against ice, or wood against asphalt. The coefficient of static friction for each pair of surfaces has to be measured experimentally because of the complexity of the microscopic interactions.

Also, note that Equation (12.5) tells us the maximum strength of the static friction force. The actual force exerted at any instant will meet the magnitude of any forces acting on the objects that tend to induce lateral relative motion, up to this maximum. Once this maximum is exceeded, the static friction ceases to operate, and kinetic friction takes over.

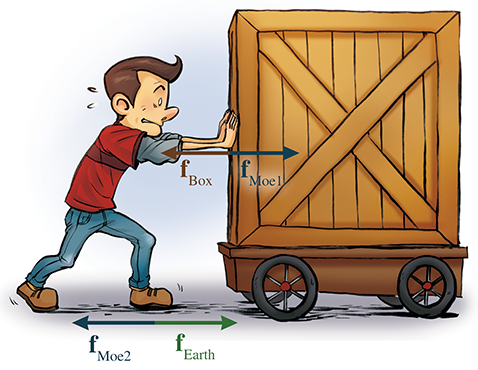

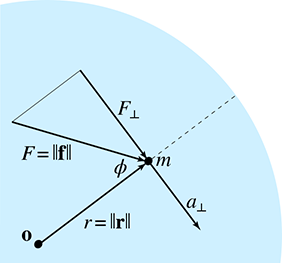

The other factor in Equation (12.5) is the magnitude of the normal force, which is the force acting perpendicular to the surfaces that prevent them from penetrating each other. One common situation occurs when an object (such as a bowl of petunias) is resting on top of another object (such as a table). The normal force in this case is simply the force required to counteract gravity. To be more precise, it is the force required to counteract the component of gravity that acts perpendicular to the surfaces and wants to smash them together. If the table is at an incline, then we can separate gravity into a normal component and a lateral component, as shown in Figure 12.4. (Inside a computer, we'd probably describe the orientation of the table with a normal vector, and use the dot product to separate gravity into the relative and normal components, as we described in Section 2.11.2.) Since the bowl and the table do not accelerate relative to each other, we know that the normal force of the table pushing against the bowl must be exactly equal to the normal component of the force of gravity pulling the bowl towards the table.

Figure 12.4 shows several free-body diagrams of identical bowls of petunias

resting on tables at various angles of inclination. Notice that in each figure, the force of

gravity acting on the bowl, labeled

In the first scenario, there is more friction available than necessary to stop the sliding. However, as the angle of inclination increases, the normal component of gravity decreases, which reduces the amount of friction available. Meanwhile, as the perpendicular component of gravity is decreasing, the lateral component is increasing, which makes the bowl want to slide. The force of static friction must counter this lateral component if the bowl is to remain in equilibrium. The center image shows the critical angle at which the lateral force of gravity is exactly equal to the to the maximum amount of friction. On the right, we imagine that we have tilted the table while holding the bowl in place, and then let go of the bowl. The maximum available friction is being applied, but it's less than was available in the center picture due to the decrease in the normal force and isn't enough to overcome the increased lateral component of gravity. Just after this picture was taken, friction switched from static mode into kinetic mode, the bowl slid off the table and shattered, and a cartoon cleaning robot scurried in through a little door in the wall to clean up themess.

Calculating kinetic friction is essentially identical to static friction. The only difference is

that we replace the subscript

The direction of the force of kinetic friction is always opposed to the relative motion of the surfaces. (Remember, according to Newton's third law, there are actually two forces, one pushing against the bowl, and the other against the table, and they are in opposite directions.) As we said earlier, the coefficient of kinetic friction is usually less than the coefficient of static friction. Thus, if we increase the angle of the table ever so slowly so that static friction is just overcome, the petunias will begin to accelerate, based on this difference between kinetic and static friction. Coulomb's primary contribution to the theory, sometimes called Coulomb's law of friction, was that the force of kinetic friction does not depend on the relative velocities of the surfaces, so, unlike static friction, there is no distinction between the effective force and the maximum force.

Notice that the amount of area that the two objects are in contact does not appear in Equations (12.5) or (12.6). For example, let's say we repot the petunias in a taller bowl with a smaller footprint but the same weight. We have reduced the surface area where the bowl and table are in contact, but all of the forces depicted in the free-body diagrams in Figure 12.4 remain the same. Doing this would not change the angle at which the bowl would begin to slide! Although it might seem like a larger surface area would give the objects more to “grab” with, this is offset by the decrease in pressure, since the same total normal force is now distributed over a smaller contact area. Now, a very tall bowl may begin to tip over before it begins to slide. But this is a matter of rotation, the increase in the tendency to rotate being caused by an increase in the lever arm resulting in a greater torque. We cover these issues in Section 12.5.

12.2.3Spring Forces

There's one more class of force that is important enough to discuss in its own section: the forces exerted by a spring disturbed from its equilibrium position. Why do we discuss this admittedly peculiar class of force? Have springs suddenly become prominent features in video games and their accurate simulation an important gameplay feature? Actually, yes. Even if you don't see very many literal springs in a video game, there are likely very many “virtual springs” at work. Springs exhibit a general behavior that is very useful for enforcing constraints, preventing objects from penetrating, and the like.

This section presents the classic equations of motion for damped and undamped oscillation. It covers undamped oscillation first, and then damped. It's often the case in a video game that programmers use a virtual spring (often in the form of a spring-damper system) when really what they are using is a control system. There are certain advantages to be had when the physical nature of the problem is dropped and we think of it purely in mathematical terms. (Indeed, many times the problem was never really physical to begin with, and was only recast in physical terms so that the spring-damper apparatus could be applied.)

Like the friction law, the force law for springs is a surprisingly accurate approximation to the macroscopic behavior that is the result of complicated microscopic interactions. Consider a spring with one end fixed and the other end free to move in one dimension. When the spring is at equilibrium with no external forces on it, it has a natural length, called the rest length. If we stretch the spring, then it will pull back to try to regain its rest length. Likewise, if we compress the spring, it will push back. But how do we know the strength of the force in each case? That's what the force law tells us.

The force law for springs is known as Hooke's law, and it basically says that the

magnitude of the restorative force is proportional to the difference from the current length and

the rest length (provided the force does not exceed a value called the

elastic limit, which varies with the material used to construct the spring). If we let

The constant

or you can just think of

The really interesting thing about springs is how they behave over time. To see this, let's restate Hooke's law in a way that focuses on the kinematics of a particle that is being acted on by restorative forces. Specifically, we're interested in functions for the position, velocity, and acceleration of a particle.

Things get easier if we adopt a reference frame where the position

You should convince yourself that this is equivalent to Equation (12.7) before continuing.

Equation (12.8) makes a statement about the relationship

between the position function and the acceleration function; but what we really want is the

function

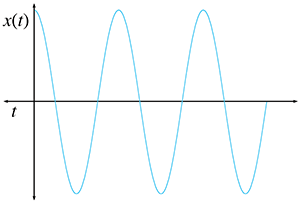

We can make a pretty good guess at the form of

This function ought to look familiar to you: it's the graph of the cosine function. Let's see

what happens if we just try

which is very close, but we're missing the factor of

To understand where

One verifies that this is a solution to the differential equation by plugging it into

Equation (12.8). Remembering that

The quantity

and we can write the solution as

hence the reason for the name “angular frequency” becomes apparent.

So we have found the kinematics equation for the spring. Or, perhaps we should say that we have

found a solution to the differential equation. There are some degrees of freedom inherent

in the motion of the spring that are not accounted for in

Equation (12.9). First, we are not accounting for the maximum

displacement, known as the

amplitude of the oscillations and denoted

It would appear that we have three more variables which need to be somehow accounted for in our

equation if it is going to be completely general. As it turns out, the three variables we have

just discussed—the amplitude, initial position, and initial velocity—are interrelated. If we

pick any two, the value for the third is locked in. We'll keep

Now let's make some observations. First, remember that the sine and cosine functions are just

shifted versions of each other:

Second, consider the frequency of oscillation. The sine and cosine functions have a period of

Notice that the frequency of oscillation depends only on ratio of the spring stiffness to the

mass. In particular, it does not depend on the initial displacement

In many situations, the frequency is the important number we wish to control. This is especially the case for “virtual springs,” which are really control systems in disguise. In these situations, we don't need to bother with spring constants or masses, and we can write the equation of motion directly in terms of frequency, as

Simple harmonic motion in terms of frequencySo far, we have been studying a physically nonexistent situation in which the restorative force is the only force present, and the spring will oscillate forever. In reality, there are usually at least two more interesting forces. The first of these forces is an external force, sometimes called the driving force, that acts as the “input” to the system and causes the motion to begin in the first place. The other force is the friction that any real spring experiences, which eventually causes the motion to cease. The general term used to describe any effect that tends to reduce the amplitude of an oscillatory system is damping, and we call oscillation where the amplitude decays over time damped oscillation. Damping forces are particularly important for our purposes, so let's discuss them in more detail.

The most common model for the damping force is a simple one that acts proportional to velocity but in the opposite direction, similar to the friction law. (Unlike the friction laws from the previous section, we don't have any of the business concerning the normal force.) The force is simply

Damping force

where

The damping force has an extremely simple form, but just as with the restorative force, things get interesting when we study the motion over time. Qualitatively, we can make some basic predictions about how damped oscillation of a spring would differ from undamped oscillation of the same spring. The more obvious prediction is that we would expect the amplitude of oscillation to decay over time, meaning the maximum displacement at the crest of each cycle is a bit less than the previous one. Like the force of friction, damping tends to remove energy from the system. The second observation is only slightly less obvious: since damping in general slows the velocity of the mass on the end of the spring, we would expect the frequency of oscillation to be reduced compared to undamped oscillation. Those two intuitive predictions turn out to be correct, although, of course, to be more specific we will need to analyze the math.

Combining the restorative and damping forces, the net force can be written as

To derive the equation of motion, we will need accelerations, not forces. Applying Newton's second law and dividing both sides by the mass, we have

Next we rewrite this in terms of two new quantities. The first quantity,

The second quantity is called the damping ratio, not to be confused with the damping

coefficient

In just a moment, when we explain the qualitative meaning of

Substituting the undamped frequency

Readers with training in differential equations should recognize Equation (12.12) as a second-order linear homogenous differential equation with constant coefficients, which is one of the very nicest differential equations we could hope for, meaning we can actually solve it with pencil and paper. Readers without this training shouldn't worry, because it won't be needed to understand the answer, to which we now fast forward, skipping the derivation. There are three distinct cases: underdamping, critical damping, and overdamping.

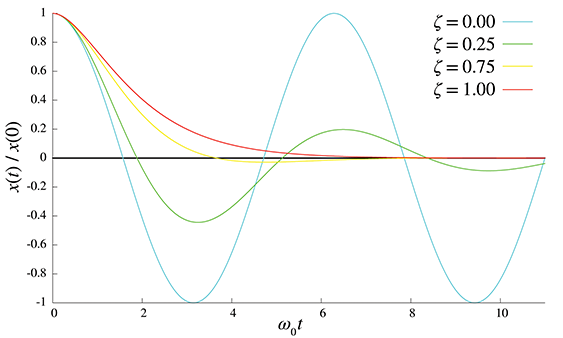

When

where

The constants

Using

Your common sense tells you that as we increase the damping ratio, the frequency of oscillation

decreases; consulting Equation (12.14), we see that at

where

Critical damping is just the right amount such that the system decays as quickly as possible without oscillation. If the damping is decreased, the system is underdamped, as previously described, and will oscillate. If the damping is increased, the system is overdamped; it will not oscillate, and the rate of decay will be slower than the rate at critical damping. Figure 12.6 shows how the damping value affects the behavior of a system.

Now that we've reviewed the classic equations that may be found in any physics textbook or on wikipedia.org, let's say a few words about how spring-damper systems are used in video games as control systems. In

general, a control system12 takes as input a function of time that represents some target value. For example, our camera code might compute a desired camera position based on the player's position each frame; some AI code might determine an exact targeting angle for an enemy; we may have a desired player character velocity based on the instantaneous amount of control stick deflection; or we might have a desired screen-space position for some highlight effect, based on the currently selected choice in a menu. In any case, the current value of the input signal is known as the set point in control system terminology. The set point is essentially the rest position of the spring, and the input signal is like somebody taking the other end of the spring and yanking it around. (So it's similar to a driving force, only usually what we have is a function describing a position rather than a force or acceleration.)

The job of any control system is to take this input signal and produce an output signal. To go back to our earlier examples, the output signal might be the actual camera position to use for each frame, or the actual animated targeting angle the enemy will use to aim the weapon, the actual player character velocity, or the actual screen-space position of the highlight. For many control systems, the actual position and set point are not used; rather, only the error is needed. Of course, an obvious question is, if we know the “desired” value, why don't we just use that directly? Because it's too jerky. In the same way that the shocks and springs on a car (a classic example of a spring-damper system) don't just pass along the elevation of the road directly to the car, a control system in a video game is often designed to “smooth out the bumps” caused by sudden state changes that might make the camera snap to a new position or the player jerk into motion. The camera or screen-space highlight are nonphysical examples in which the quantity of “mass” is not really appropriate and is dropped. But the differential equations are still the same, and they have the same solution. Stripped of the spring metaphor, we are left with what is known as a PD controller. The P stands for proportional, and this is the spring part of the controller, since it acts proportional to the current error. The damper is the D part, which stands for derivative, because the action of the damper at any given instant is proportional to the derivative (the velocity). PD controllers (and their more robust cousin, the PID controller, where the I stands for integral and is used to remove steady-state error) are broadly applicable tools; they have been standard engineering tools for decades (centuries?) and are well understood. Nevertheless, they are one of the most frequently reinvented wheels in video gameprogramming.

In practice, the simulation code is a very simple Euler integration of Equation (12.11). As shown in Section 12.6.3, this is a fancy way of describing code that looks like Listing 12.1.

struct SpringDamper {

float value; // current value

float setPoint; // "desired" value

float velocity; // current ``velocity'' (derivative of value)

float c; // damping coefficient

float k; // spring constant

// Update the current value and velocity, stepping forward

// in time by the given time step

void update(float dt) {

// Compute acceleration

float error = value - setPoint;

float accel = -error*k - c*velocity;

// Euler integration

velocity += accel*dt;

value += velocity*dt;

}

};

Different cars have suspensions that are tuned differently; sports cars are “tighter” and the

cars retirees like to drive are smoother. In the same way, we tune our control systems to get the

response we like. Notice that the simulation uses the

Notice that the kinematic equations (12.13) and (12.15) are not needed directly by the simulation, nor do we need to explicitly distinguish between underdamped, critically damped, or overdamped.

Before we leave this discussion, we must mention that the second-order systems we have described

here are certainly not the only type of control system, nor even the simplest, but they do behave

nicely under a very broad set of circumstances and are easy to implement and tune. Another

commonly used control system is a simple first order lag,

12.3Momentum

Let's say that Moe's box from Section 12.1.3 has a mass

While we don't know the exact history of Moe's pushes, we do know what the “total” was, in the

sense about to be described. Assume that Moe did make one push with a constant force

Substituting

The left- and right-hand sides of Equation (12.16) illustrate two different ways of thinking about the important concept of momentum. Momentum is the correct quantity to track in order to quantify the “total amount of pushing.”

Let's do dimensional analysis on Equation (12.16), first just to verify that it makes physical sense—it isn't intuitively obvious that these two products would bear the same physical meaning—and also to see what the units of momentum should be:

Note that momentum is a vector quantity, having both magnitude and direction.

To understand what momentum is, let's look at the two sides of Equation (12.16). First consider the left side, which interprets momentum as a product of mass and velocity. In fact, somewhere in almost every physics textbook you can find Equation (12.17).

The variable

Equation (12.17) makes it clear that the momentum of an object is an instantaneous

property of an object. By saying this, we mean that we can define its value knowing only its

instantaneous state, without worrying about how it got into that state. Furthermore, if you think

of momentum as the “total amount of pushing” required to stop a moving object, then it

certainly is intuitively appealing that it should be the product of mass and velocity. If the

object is small and moving slowly (a pencil rolling on a desktop), only a small total force will

suffice. If it's fast (a bullet) or heavy (a car that somebody left parked on an incline without

the emergency brake set), a larger amount will be needed. If it's fast and heavy (an

airplane coming in for a landing), then you'd better get out of the way. The equation

Although the memorable equation

In fact, if we generalize the equation

which is just Newton's second law to which we've added the notation “

Substituting Equation (12.18) into Equation (12.19), assuming that the mass does not vary over time, we have

Finally, if we let

Since integration is a “summing up” process, Equation (12.20) confirms our interpretation of momentum as the result of continued application of force over time. (Note: in the preceding integrals we omitted the constant of integration, essentially assuming the initial velocity was zero.)

Remember that integration and differentiation are inverse operations. By taking the derivative

of both sides with respect to

The net external force on a system is equal to the rate of change of momentum of the system.

Equation (12.21) is not just an interesting observation about force and

momentum, it's a completely valid way to define force. In fact, although the modern

presentation of Newton's laws is in terms of forces and masses, when Newton himself first

expressed the laws, he wrote in terms of momentum. He used the word “motion,” but from his

writings we understand that he used that word in a very particular sense, and he really was

talking about momentum. (The word momentum hadn't been attached to that concept yet. Remember, he

was the guy laying down all the ground rules.) Newton's second law was originally expressed in a

form that more closely resembles Equation (12.21) than the

12.3.1Conservation of Momentum

Let's return to our investigation into what happens when Moe pushes against the Earth to get his box moving. Newton's law tells us that the Earth, not having anything else to push back on, receives a net force, and thus an acceleration (and a torque, which we discuss later). Yes, you cause the Earth to accelerate when you push boxes as well as when you take each and every step! Of course, the Earth's mass is so large compared to Moe's force that this acceleration is small. Not only that, but Moe's force pushing the box to the east might be canceled out by Joe's force in North Dakota pushing his box to the west at the same time. An issue even more important than these two facts involves the “accounting laws” of physics: “there is no such thing as free momentum.” Moe doesn't need Joe to balance out his force; as it turns out, he can't help but do it all byhimself!

Observe that once Moe sets the box in motion, he will need to eventually stop it. According to Newton's first law, the only way to stop a moving box is through a force, and according to the third law, this can happen only if there is some other object involved to receive the opposite force. Perhaps the box bumps into a tree and comes to a stop. (We consider the tree to be part of the Earth. Remember that Newton's third law justifies our treatment of connected objects as a single object, provided that they remain rigidly connected.) To stop the box, the Earth must push against it with a force that is in the opposite direction that Moe pushed to start it moving. However, we know that the “total amount” of pushing must be the same, meaning the Earth must push back with a strong enough force, or for a long enough duration (perhaps Moe's box rolls into a patch of tall grass) to bring the momentum of the box down to zero. So you see that whatever acceleration the Earth received as a result of getting Moe's box in motion must always be exactly canceled by the force required to bring the box to a stop.

But perhaps Moe's box does not come to a stop by pushing directly against the Earth. Let's say it bumps up against Joe's box. Voila! We have stopped Moe's box, and no force has been applied to the Earth. But now, by Newton's third law, Joe's box must begin accelerating, and we are back to where we started with a moving box that will continue moving unless it receives a force to bring it to a stop. Eventually, the only way we can stop this chain reaction started by Moe's push against his box is for something, eventually, to push against the Earth.

We can generalize this idea even further. We are justified in treating the entire Earth, and all of its moving parts, as a single particle with all of its mass centered at some location known as the center of mass. (We talk more about this special point in Section 12.3.2.) The pushing against the Earth of people like Moe results in transfers of momentum between the objects in the system. Each part will move around within this very complicated system relative to the other parts and relative to the center of mass of the system. However, the total amount of momentum of the entire system is always a constant, unless there are external forces acting on the system. This is known as the law of conservation of momentum.

The conservation of momentum is precisely what Equation (12.21)is saying. It's certainly an experimentally verified fact, but it also follows naturally as a result of Newton's laws. Section 12.4 discusses how to use this important law to simulate the collision of objects. However, before we get to that, we need to take a closer look at the center ofmass.

12.3.2The Center of Mass

Our discussion of momentum has led us to consider the center of mass of an object. Let's say a few more words concerning this important concept. For everyday purposes, the center of mass is equivalent to the center of gravity, which is essentially the point around which the object is perfectly balanced. If we balance an object on the tip of a very thin rod or hang it from a wire, then the rod or wire will be in a line that contains the center of mass.

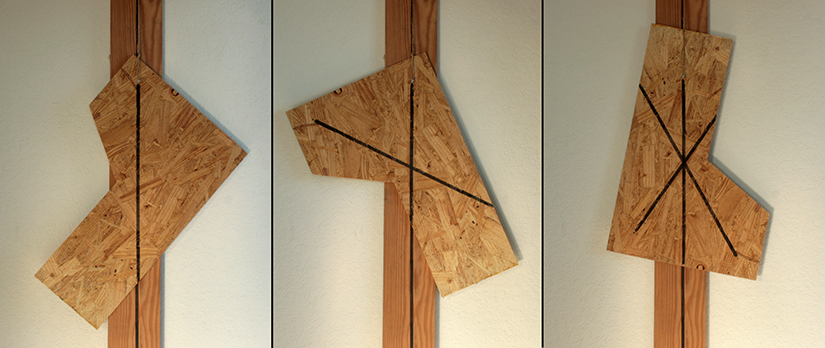

Before we discuss how to compute the center of mass mathematically, let's see how we can measure it experimentally. Imagine that we have some object with an odd shape, or of an irregular density. We can determine its center of gravity by hanging the object from any arbitrary point on the surface of the object. This defines a vertical line upon which the center of gravity must lie. By repeating the experiment with a different point on the object and finding the intersection of those two lines, we can locate the center of gravity.

The authors performed this experiment on a piece of particle board, as shown in Figure 12.7. First, the board was cut into a purposefully asymmetric shape. Next, we chose three arbitrary locations from which to hang the board, and when the board had finished swinging around, we drew a heavy line on it, coincident with the string by which the board was suspended. Sure enough, physics worked, and the third line passed right through the intersection of the first two lines, at the board's center ofmass.

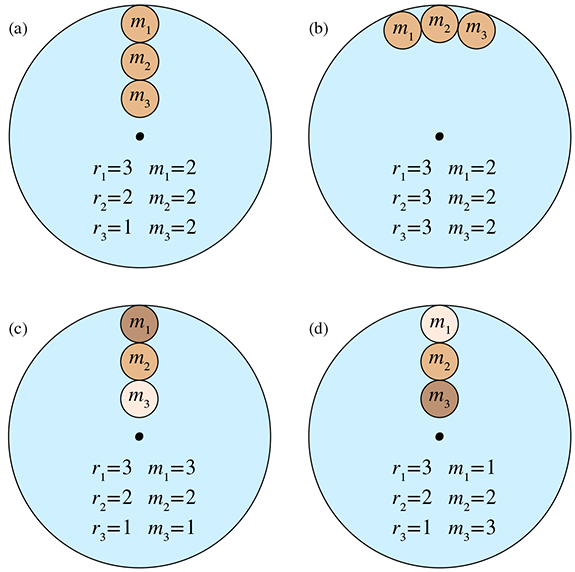

To compute the center of mass mathematically, we imagine the object being divided up into a very

large number of small

“mass elements.” If there are

In Equation (12.22),

For our purposes, the most important property of the center of mass is that if the object rotates, it will rotate about its center of mass. This assumes, of course, that the object is freely rotating and there isn't a constraint compelling it to rotate about some other point.

As an example, consider a sledge hammer. Clearly, the center of mass of the sledge hammer is close to the heavy end of the sledge, not in the middle of the handle. Assume we throw the hammer across the room. As it tumbles through space, any arbitrary point on the hammer will trace out a complicated spiraling shape. The center of mass, however, moves in a parabola, in perfect agreement with the kinematics equations we learned in Chapter 11.

The authors couldn't resist the opportunity to chuck big objects around, so we verified this hypothesis experimentally, and you can, too.13 We started with the odd-shaped piece of particle board, whose center of mass had been experimentally located and clearly marked. Next, the fun part:

we threw it in the air and took a series of pictures of its trajectory with a camera mounted on a tripod. Finally, we merged these frames together into a single image, and used least-squares to fit a parabola through the points marking the center of mass. The result of the experiment is Figure 12.8.

One small note: When fitting the parabola, we did not include the first frame in the data set. As you can see, on the first frame the board is still in the assistant's hand, and thus has not yet begun its (parabolic) free fall trajectory.

Because an object will rotate about its center of mass when allowed to rotate freely, in a physics simulation is it highly advantageous to select the origin of your object to be at its center of mass. Of course, you may have good reasons to put the origin of the object elsewhere. For example, you may have a graphical representation of an object with the origin placed somewhere that made sense to the artist who made that model. In general, if you place the origin somewhere other than the center of mass, then you will likely have to deal with two “positions” of the object: one position within the physics system that describes the world coordinates of the center of mass, and another, perhaps in the rendering system, for the origin of your

graphical model. The code that translates between these two conventions is likely to be found either in the interface with the physics engine (for example, the code that updates the position of the objects after the physics simulation has run), or the code that sets up the reference frame for the object during rendering.

The center of mass is fixed for a rigid body such as a sledge hammer; this assumption has been implicit in the whole discussion; otherwise, it wouldn't make sense to advise setting the origin at the center of mass. However, for a general system with moving parts, such as Earth, the center of mass is a dynamic property, not a constant. The center of mass shifts around within the object as the parts are reconfigured.

For example, imagine if all of the people in the world decided to visit the North Pole at the same time. Assuming we would all fit and there were enough earmuffs to go around, the Earth's center of mass would shift towards the North Pole. This new center of mass, however, would trace out the exact same trajectory as the old one would have. In other words, while the trajectory of the Earth's geometric center would be slightly “southward” from where it would have been if we all stayed at home, the trajectory traced out by the center of mass is the same in either case.

Or, let's say that instead of visiting the North Pole, we all decided to go to the Galapagos Islands, which is very near the equator. Would Earth's rotation suddenly get all “wobbly” like an out-of-balance ceiling fan? No! Instead, the center of mass would shift towards the Galapagos Islands, and the Earth would rotate about this new center of mass. So although the rotation, when viewed from above, might appear asymmetrical, since the rotation would not be about the center of the spherical Earth (assuming the Earth were perfectly spherical), the rotation would be smooth. An unbalanced ceiling fan is wobbly because it is not free to choose its axis of rotation, and so it must be balanced in order to align the center of mass with the fixed axis of rotation. Earth, however, is not connected to anything, and it is free to rotate about its center of mass, wherever that center of mass may be.

Of course, all the people on Earth put together have less mass than our moon, so our discussion has been misleading. The point that traces an ellipse as we orbit the sun isn't the Earth's center of mass at all! It is the center of mass of the entire Earth-moon system. This point isn't really close to Earth's geometric center, although it is beneath the surface, but only because Earth is so much more massive than the moon. As the moon orbits the Earth, the center of mass of the system shifts around within Earth. It is this imaginary point that orbits the sun, not the center of mass of Earthitself.

12.4Impulsive Forces and Collisions

In video games, things are always ramming into each other, so it seems appropriate for us to spend some time talking about collisions. As we've mentioned, in the real world, momentum does not change instantaneously; rather, a large force acts over a very small period of time. However, despite reality (remember the first law of video game physics), it is frequently the case that the interval during which these forces act is below the resolution of our physics time step, and for practical purposes we can consider the change in momentum to have happened instantaneously. The most important and common scenario is when the object is involved in a collision. Since the mass of most objects is constant, an instantaneous change in momentum usually boils down to an instantaneous change in velocity.

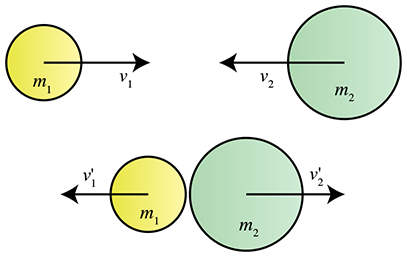

Consider two objects traveling towards each other in one dimension, with masses

Using the momentum relation

The change in momentum of each object, according to the law of conservation of momentum, is

actually the result of a force acting over time. However, we think of the collision here as

producing an instantaneous change in momentum of the two objects. A force that is treated in

this way is known as an impulsive force, or more simply, an impulse. Since an

impulse is an immediate change in momentum, it has the same units as momentum:

When two objects collide, many things can happen, even if we assume they remain intact. A likely

scenario is for them to bounce off of each other, changing the signs of both

In general, we cannot predict the individual velocities

12.4.1Perfectly Inelastic Collisions

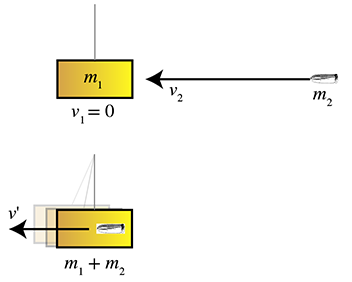

A classic example of an inelastic collision is a gun firing a bullet into a block. Assume that, as illustrated in Figure 12.10, a block of wood weighing 2.00 kg is at rest, hanging from a wire whose mass is neglected. We fire a gun at the block, and the bullet, which has a mass of 10 g, strikes the block with a speed of 350 m/s. The bullet remains stuck in the block. What is the horizontal speed of the block immediately after the impact?

First, we compute the initial momentum of the system, which is all contained in the bullet:

Now we look for the resulting common velocity, which we'll denote simply as

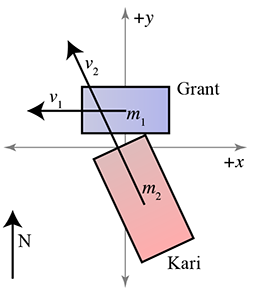

Let's look at one more example of an inelastic collision, this time in 2D. Consider a driver who runs a red light and crashes into a car crossing the intersection. Let's say that Grant is the safe driver, and at the time of the collision, Grant and his fuel-efficient hybrid have a combined mass of 1,500 kg and are traveling west at 35 km/hr. Kari,14 who is not paying attention, sees Grant's car too late, and swerves to the left. She and her car have a combined mass of 2,500 kg. At impact, she is traveling at 65 km/hr, heading 25° west of north, as shown in Figure 12.11. Assume that we can treat the collision as inelastic. What is the velocity of the crash just after the collision?15

To solve this problem, let's set up a 2D coordinate space where

The resulting velocity of the glob of two cars is simply the momentum we have just computed divided by the total combined mass:

12.4.2General Collision Response

Simple inelastic collisions can be solved by using the principle of conservation of momentum, but how do we compute the velocities in the general case? Before we can fully answer that question, we need to consider the context in which it is asked. Dealing with collisions is typically a two-step process. First, we must detect that a collision has occurred, meaning the objects are already penetrating, or that a collision is about to occur in this time step. The second step is to take measures to resolve or prevent the collision. The former task is known as collision detection, and the latter as collision response. Our purpose at this time is to discuss collisions in theoretical terms (we touch on a few practical issues related to how physics simulations really work in Section 12.6), so for now let us merely attempt a general explanation of how the momentum of rigid bodies changes in response to collision. We assume that we already know that two objects have collided, and we wish to predict their behavior after thecollision.

To do this, either in the abstract in a physics problem, or in collision response code in a digital simulation, we typically need to know not just that two objects have collided, but also where they collided, and how the two objects were oriented relative to each other at the point of contact. For example, in the car crash between Grant and Kari, we need to know that Grant's car was hit near the left door, and Kari's in her right front fender. Of course, a collision doesn't necessarily happen at a single point. Often an edge of one object may touch a surface of another, or perhaps entire surfaces are in contact. At the time of this writing, most real-time collision detection systems do not return collisions in such a descriptive manner, nor are collision response systems really capable of making use of that extra information. The closest we get is for the detection system to locate several points of contact (or penetration) and then to process that list in some way (for example, by finding their convex hull or looking for an average surface normal). In any case, the best way to do this quickly is very much at the forefront of research, and as such doesn't belong in an introductory book like this. Here we just consider the principles involved in a single point of contact. More advanced techniques build upon these principles.

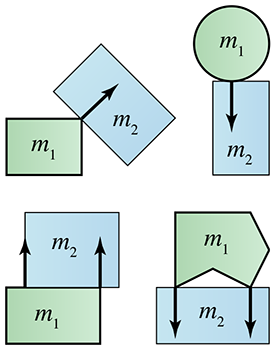

Figure 12.12 shows some example collision results that might be returned from a collision detection system. Note that each collision result (black arrow) has a point of contact (at the tail of the arrow), and a surface normal, usually assumed to be a unit vector. An arbitrary convention is chosen for which way the normal will point; in Figure 12.12 it points away from the “first” object. Furthermore, the two objects may be arbitrarily assigned the roles of “first” and “second” objects, perhaps by the luck of the draw that the objects happened to be in some space-partitioning structure. These assignments can even vary frame-by-frame, so the response calculation must be symmetric. What is not depicted in the diagram is that a penetration depth is often returned if the objects are already penetrating.

And always, we should bear in mind the first law of video game physics. Not all collisions in video games must be between “real” objects, meaning those objects that are represented in the physics system. For example, consider a game with a kick mechanic. It may be helpful to treat a kick as a “collision” with an object, even if the character's foot is not in the physics system or if this collision was determined by simple proximity tests or raycasting that were designed based on gameplay goals and not reality. (The player character may have been too far away or too close for the kick to really have hit the target; but that is irrelevant.) It might be highly useful for the response to this action to be handled in a manner similar to ordinary collisions. For example, a sound and particle effect plays, the object receives a reduction in hit points, and its visual appearance changes, etc. In this case, in order to use the same collision response code for both ordinary collisions and “virtual” collisions such as player kicks (even if it is just to get the cosmetic effects right), you may need to synthesize values ordinarily provided by the collision detection system for your “virtual” collisions, such as the mass and velocity of the foot, and the point of contact and surface normal.

One final caveat is that we are concerned only with linear momentum for now; our objects do not rotate. This means that the explanation we give in this section will be incomplete. However, it will be helpful to cover the general principles here in a context free of the extra complexity that comes with rotation.

Now to the heart of the matter. Assuming we have somehow detected a collision and obtained a position and normal, how do we determine the resulting velocities for the collision response? Here we show the usual method, following an article by Chris Hecker [7]. We start by reviewing our guiding principles.

Our first guiding principle is that, although we know that in reality a very large force acts for a short period of time, the period of time is so short relative to our time step that we will consider the collision response to occur instantaneously. That is, we will not be calculating a force, but rather an impulse, which will result in an instantaneous change in momentum of the objects.

The second guiding principle is given to us by Newton's third law: whatever (impulsive) force is applied to one object, the opposite force must be applied to the other object. The conservation of momentum law essentially says the same thing: if we change the momentum of one object, we must make the opposite change in momentum to the other object so that the total momentum of the system after the collision is the same as the total momentum before the collision.

Thus, to resolve a collision between two objects, the game plan is to compute an impulse with the proper magnitude and apply that impulse to both objects, but in opposite directions. An impulse is a vector quantity, and so we need to know its magnitude and direction. The direction is given to us already: it is the surface normal provided by the collision detection system. The details of selecting a surface normal is a matter of collision detection, not response, and will not be discussed here. But notice that if the objects move parallel to this normal, they are either making the problem worse (penetrating further) or better (moving apart and resolving the penetration). In contrast, if we assume the penetration distance is relatively small and the surfaces are locally flat and perpendicular to the normal near the point of contact, then any motion perpendicular to the surface normal does not cause the penetration distance to change. So the surface normal is really the only direction that matters.

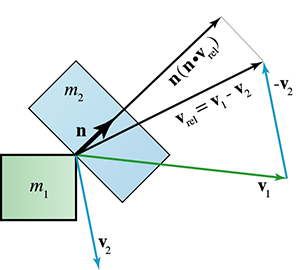

In summary, our task is to determine the proper magnitude of an impulse that will be directed

along the surface normal and will resolve (or prevent) the penetration. To merely prevent a

penetration that has not yet occurred, we need only remove any relative velocity acting parallel

to the surface normal. This portion of the relative velocity is the velocity that, if applied to

move the objects forward in time, would result in penetration. Any relative velocity acting

perpendicular to the normal is OK and does not need to be counteracted, according to our

assumption that the surfaces are locally flat near the point of contact. As illustrated in

Figure 12.13, the velocity of

Canceling the relative velocity will prevent penetration, but it's not always the correct

response. When objects collide, they don't just come to a stop next to each other—they bounce

off each other. So we're missing an ingredient that describes the difference in the collision

responses of a dropped beanbag and a dropped

SuperBall. A simple and popular collision law (though not the only one) that can be used to

discriminate between these cases is

Newton's collision law. This law introduces the

coefficient of restitution, denoted

Let's denote the magnitude of the collision response impulse as

The post-collision relative velocity is simply their difference,

Equation (12.23) can be simplified slightly in the common case that

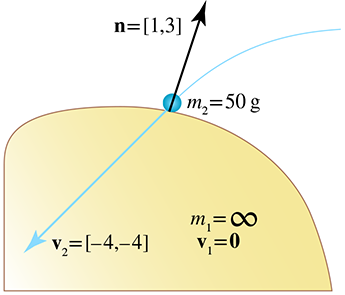

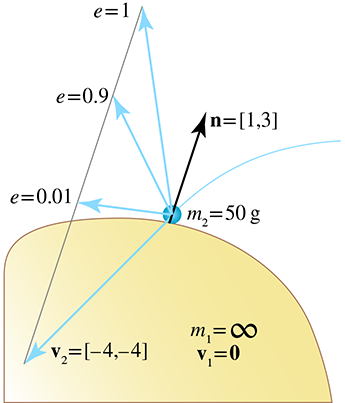

Let's work through a few examples of Equation (12.23). First, let's see how

the coefficient of restitution can be used to describe the difference between dropping a

beanbag and a SuperBall. We'll be dropping these objects onto a concrete floor, which is an

enlightening example because it shows how immovable objects can be easily handled in most physics

engines by acting as if they have infinite mass. As it turns out, the inverse mass is the

quantity we usually work with in calculations involving such special objects (as illustrated in

Equation (12.23)). Furthermore, the inverse mass (and its analog, the

inverse inertia tensor, to be discussed later) are derived quantities that are needed so

frequently that they are often precomputed. This means that physics code can often work with

immovable16 objects without treating them as a special

case, simply by setting the inverse mass equal to zero. When one of the inverse masses is zero,

we could actually deal directly with velocities and bypass Equation (12.23),

since

Let's say we have one SuperBall and one beanbag, each weighing 50 grams. To avoid making the

solution to our example completely obvious without Equation (12.23), we will

arrange for the point of impact to occur on an inclined surface, so that

To determine the resulting velocity, we first solve for

To compute the post-collision velocity, we add an impulse of

Before we show this velocity graphically, let's look at the beanbag. We treat the beanbag

collision as almost completely inelastic and use

Notice that the reduced coefficient of restitution caused the beanbag to receive a smaller

impulse scale, and the resulting bounce velocity was also lower. This difference is shown

graphically in Figure 12.15. For

comparison, we've also included a perfectly inelastic collision (

It is obvious from the beanbag trajectory in Figure 12.15 that an important aspect of collisions is not captured by the model: friction. The velocity perpendicular to the normal is the same before and after the collision. We would expect an object like a beanbag to scrub off a great deal of horizontal velocity as a result of the collision—in fact, it might come to a stop completely. The correct thing to do is to add in a perpendicular component to the impulse. However, correct handling of friction is, in general, a tricky business, and it remains at the forefront of real-time simulation research. Many current methods for calculating the horizontal impulse (especially for sliding contact) fall under the category of “completely fudged.”

In the previous example, we only had one “live” object and the other object was inert. This is a special case, and the equations could be simplified. (As we mentioned earlier, the mass of the projectile cancels itself out and is not needed.) In Exercise 9, we ask you to consider what would happen if Grant and Kari's collision were not perfectly inelastic; the full power of this law is needed in this case. We show how to handle collisions where the objects are free to rotate in Section 12.5.4.

We have been assuming thus far that the objects are in contact, but are not yet penetrating. This might not be the case, depending on the overall strategy used to resolve collisions. One technique is to attempt to reverse the simulation in time back to the point of contact. This can be difficult to do efficiently because there are frequently many, many collisions that happen at different times within a single time step. Furthermore, defining “exactly in contact” is difficult when using floating point math. Another strategy is to simply allow penetration, and apply the impulse to objects that are already penetrating. In this case, the impulse must do more than remove the relative velocity to prevent (further) penetration. The resulting relative velocity must be sufficiently large to separate the objects by the end of the time step, after it has been integrated into the position. In other words, the positions of the objects will be advanced at a rate according to the calculated velocities; after this update, the penetration needs to be resolved. Or at least it needs to be mostly resolved. There are some advantages to allowing some small penetration. All of these issues are a bit outside the realm of established principles and fall more under the heading of current research,17 and they will not be discussed here.

12.4.3The Dirac Delta

Before we leave linear dynamics and talk about rotational dynamics, let's mention briefly one bit

of mathematical notation you might see, especially in the context of impulses. As we've said,

many natural phenomena (such as momentum) do not change instantaneously in theory, but for

practical purposes we treat them as changing instantaneously. Furthermore, it is often the case

where a body of mathematical tools exists to handle continuous functions (or, equivalently,

“signals”), and we wish to apply those tools to signals with discontinuities. There is a handy

mathematical kludge that can be used to encode a discontinuity in a function such that it can be

integrated. It is known as the Dirac delta, and is usually denoted with the lowercase

letter delta, for example

The symbol

Armed with the Dirac delta, we can differentiate functions with discontinuities. For example,

let's say the velocity of a baseball being struck by a bat at time

We can differentiate this expression by using the Dirac delta as

which can be read as “an impulse of magnitude 260 at 2.” Remember that the

The Dirac delta comes up in a variety of contexts where tools from continuous math are applied to discontinuous signals. For example, in graphics, the screen-space image is a signal with inherent discontinuities, and we need to sample this signal and reconstruct it. The user's input via the controller is another signal that exhibits discontinuities. The Dirac delta and other related symbols (such as the ramp function and Heaviside's step function) are helpful in discussing and manipulating such signals.

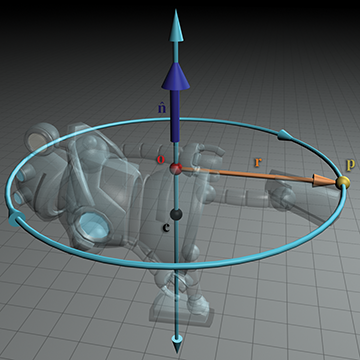

12.5Rotational Dynamics

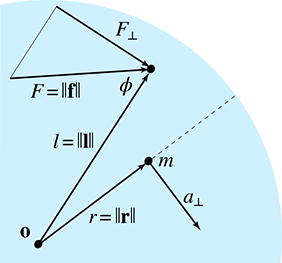

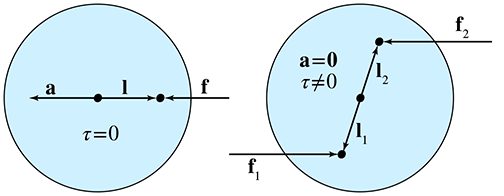

We are now ready to extend the ideas we have learned about particles to rigid bodies. Particles have position, but until now we have not concerned ourselves with orientation. Likewise, particles have mass, but until now we have not thought about the size or shape of a particle and how that mass was distributed. The key linear quantities and laws each have rotational analogs, and there is a certain beautiful correspondence between them. This correspondence is certainly pedagogically convenient and will be leveraged in our discussion. As we did for linear dynamics, we first define the basic kinematics quantities and consider those issues related to describing the rotation without worrying about the causes of the rotation. We then examine the rotational analogs to mass, force, and momentum, although we will discuss these topics in a different order.